Spring 2023: Traces of Macbeth: A Study of Text Reuse

Table of Contents

Analysis

Versions of single Macbeth

One interesting aspect of this project is that we were able to trace the individual versions of Macbeth published during the 18th century. According to our data, until 1773, all of the individual editions of Macbeth were either printed in London by the Tonson house, or issued outside of London (The Hague, Dublin, Edinburg, Glasgow and Cork), “where Tonson’s real or imagined copyright invoked no terrors” (Walsh, 2012), by other printers. The first single Macbeth produced in London by a printer other than Tonson was Jennen’s 1773 edition. Three additional non-Tonson, London-printed editions were issued in 1780, 1785 and 1794.

As seen in the above graph, out of 27 editions of single Macbeth published in the 18th century, 13 were published in England (11 in London, two in York), while 12 were published outside of England (five in Dublin, three in Edinburgh, two in Glasgow, two in The Hague, one in Cork, and one in Göttingen, Germany). Of course, something to consider when looking at these results is the representativity of our corpus. In both the ECCO and the EBBO Great Britain is overrepresented (Gavin, 2017; Tolonen, Mäkelä, Ijaz & Lahti, 2021), so it is not impossible that other single Macbeth versions that we are not aware of were published outside of Great Britain.

Since we were not able to attribute text reuse instances to specific Macbeth editions, we cannot tell how the different editions were reused over time. This is because our data is created by finding similar text snippets in different documents using the BLAST software. A reused snippet of Macbeth shows up many times in the data set, since that snippet exists in more or less the same form in many of the Macbeth editions, even though the author of the target text most likely took it from a specific edition. For our analysis we dropped the duplicate reuses randomly, because we did not know how to choose the right Macbeth edition for each reuse instance. Thus, we cannot compare editions over time.

Overall, there is a clear upward trend in reuse of Macbeth over the 18th century. Looking at the number of reuse instances in the 18th century this trend is hard to see. Figure (X) shows the number of reuses per each year in the 18th century. The figure shows strong variation year to year in the count of reuses. Moreover, there seem to be more reuses in the middle of the 18th century.

However, the year to year variation in the number of reuses of Macbeth is due to individual books, such as Samuel Johnson’s dictionaries, which reuse Macbeth many times. Figure (Y), which shows the number of books reusing Macbeth over time, demonstrates that more books reuse Macbeth in the later part of the 18th century.

Who reused Macbeth and how?

As stated in the previous section, the reuse of single Macbeth remarkably increased as the 18th century advanced. The geographical distribution of the publication of works reusing Macbeth during the 18th century reveals nothing too surprising. According to our data, most of them (470) were published in London, followed by Dublin (77) and Edinburgh (28).

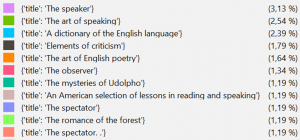

We were likewise able to shed some light on which works reused Macbeth more extensively, and on the connections between them. The graph below is a directed bipartite graph of the reuses made by the publications. Every colored node represents a publication with a title (multiple editions of the same publication are shown). Every white node is a unique reuse passage from Macbeth, the size of a white node represents how many publications are reusing that passage. A directed edge from publication to passage edges represents a reuse, the edge has the same color as the publication. Visually, it is clear that A dictionary of the English Language dominates the graph by number of reuses. It is followed by some other publications like The Speaker, The Art of English Poetry, and The Art of Speaking.

Interestingly, since each passage in the graph is unique (derived from our passage clustering), we can see how publications tend to not quote the same passage of Macbeth through the size of the nodes. The majority of the passages reused by each publication seem to be unique to that publication (and therefore are smaller nodes). This is especially true for A dictionary of the English Language, which shares very few passages with other publications. Proportionally, the other publications share more reuse passages amongst themselves, but still mainly reference different passages.

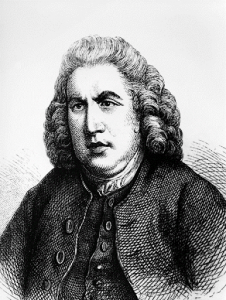

As the graph after this paragraph demonstrates, the authors that were found to be the most prominent reusers of single Macbeths, are, in descending order of number of reuses, Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), William Richardson (1743-1814), Sir William D’Avenant (1606-1668), Edward Byyshe (fl. 1702–1712), Richard Cumberland (1732-1811), William Enfield (1741-1797), Elizabeth Montagu (1720-1800), James Burgh (1714-1775), John Boydell (1720-1804) and Elizabeth Griffith (1727-1793).

Because of Samuel Johnson’s relevance for text reuse, in what follows we will discuss him in more detail. Afterwards, we will have a closer look at two other important reusers: William Richardson and Edward Byyshe.

Samuel Johnson

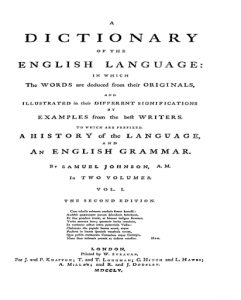

Based on the data analyzed through computational methods and visualizations, it is evident that Johnson Samuel and his 1799 edition of A Dictionary of the English Language hold a prominent position both in terms of Macbeth reuse. Notably, the 1799 edition of the dictionary emerges as the most significant source quoting from Macbeth, offering insights into its popularity and widespread use during that period. This particular edition of the dictionary not only provided a comprehensive documentation of the English Language as it existed in the 18th century, but also drew extensively from Macbeth (Crystal, 2018).

While Johnson’s references to Macbeth can be found in his other works, it is the dictionary that stands out as a primary medium for the abundant reuse of Macbeth. Therefore, we chose “A Dictionary of the English Language” as a case study to investigate the traces of Macbeth and explore further the content and context of the reuses. By doing so, we aim to uncover the reasons behind the frequent usage of Macbeth quotes and understand how they facilitated Johnson Samuel in expressing himself while documenting the English language. Through this examination, we seek to shed light on the significance of Macbeth within the dictionary and its contribution to linguistic and literary discourse.

Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language was a groundbreaking work and a significant contribution to English lexicography. The dictionary, first published in 1755, contained around 42,000 words, and each word was accompanied by definitions, etymologies, and illustrative quotations. Johnson’s use of illustrative quotations from various works of literature was an innovative approach that helped to make his dictionary a valuable resource for anyone interested in English language and literature. Johnson drew his examples from a wide range of sources, including the Bible, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, and other influential writers of his time. The quotations he used to illustrate each word were carefully chosen to showcase the word’s different meanings and nuances. In some cases, the quotations he used became famous phrases or idioms (Library, 1755).

One reason why Johnson may have reused a lot from Macbeth is that Shakespeare’s works were among the most widely read and influential texts in the English language, even in Johnson’s time. As such, they would have been a rich source of examples for Johnson to draw upon in his dictionary. Additionally, Macbeth is in particular notable for its use of poetic language and complex wordplay, which would have made it an especially fruitful source of linguistic examples for Johnson (Britannica Encyclopedia).

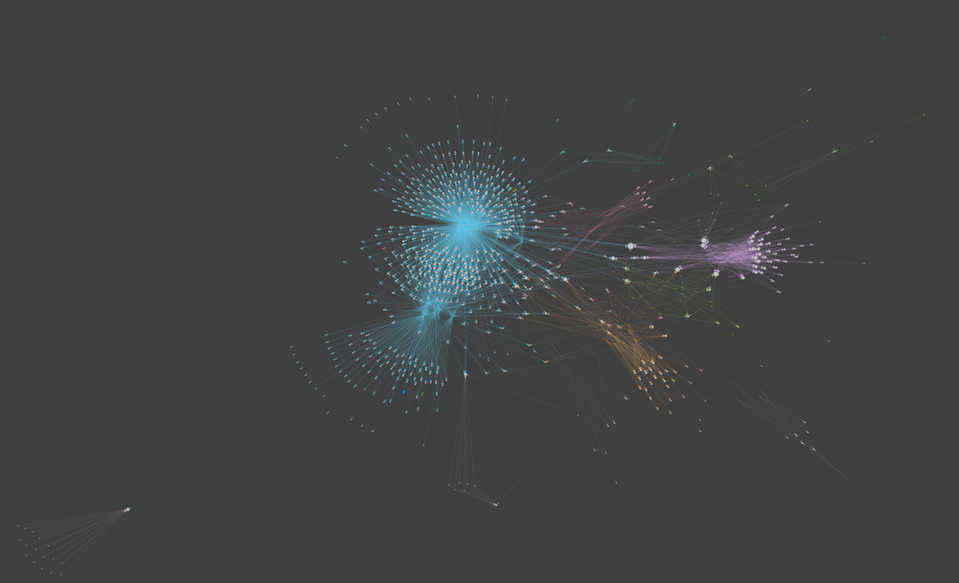

Most reused passages of Macbeth from A Dictionary of the English Language, 1799:

Example 1. The most reused passage of Macbeth in the Dictionary within its context.

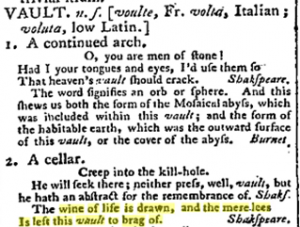

“The wine of life is drawn, and the mere lees

Is left this vault to brag of”

It is the most reused passage that was determined by computational methods and it was reused eight times in this edition of the dictionary. The phrase is a line spoken by Macbeth in act 2, scene 3 of the play. In this scene, Macbeth has just murdered King Duncan and is filled with guilt and remorse. He speaks these words to the porter who is attending to the door of the castle. Johnson used the quote to show how the word “vault” was used metaphorically in Macbeth. The word “vault” in this context is a symbol for the world or existence that proudly boasts about its empty and unimportant leftovers. The choice to include this quote in the dictionary entry for “vault” highlights his recognition of the power of Shakespeare’s language and his intention to provide vivid and meaningful examples to aid readers in understanding the nuances and connotations of words. Including passages from Macbeth shows how influential and important Shakespeare’s works were in shaping the English language even during Johnson’s time.

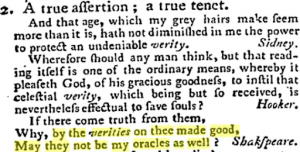

Example 2. “By the verities on thee made good,

May they not be my oracles as well”.

In this part of the play, Macbeth is thinking about the predictions given to him by the witches, who have supernatural powers. He talks about the “verities,” which means sacred truths or divine forces, and wonders if they can also guide him and tell him what will happen in the future. Macbeth is questioning whether these prophecies can be trusted and if they will shape his own destiny and if he can trust them as reliable oracles. This moment shows Macbeth’s ambition and his willingness to rely on supernatural sources for guidance. It sets the stage for the tragic events that unfold as Macbeth becomes obsessed with gaining power at any cost.

In different situations, we observe the recurrence of identical passages being utilized with distinct purposes.

1.

2.

William Richardson

Richardson William, along with authors like Samuel Johnson, and Edward Bysshe, was known for reusing passages from Shakespeare’s Macbeth in his writings. He was a prominent writer of his time who extensively referred to and criticized Shakespeare’s dramatic characters and language. In his works A philosophical analysis and illustration of some of Shakespeare’s remarkable characters (1784) and Essays on some Shakespeare’s dramatic characters (1798) he analyzed the characters of Macbeth, exploring their emotions, moral attitudes, and the themes of moral decay and tyranny of the characters. His criticism received praise and attention in publications like the Critical Review and the Monthly Review, particularly for his philosophical approach to the characters of Hamlet and Macbeth. Richardson’s works were appreciated for the insights into the study of the human mind and his analysis of Shakespeare’s characters (Babcock, Jan., 1929)..

In A philosophical analysis and illustration of some of Shakespeare’s remarkable characters (1784), his main objective was to explore Shakespeare’s characters and their emotions to help us comprehend our own human passions. He believed that by examining the portrayal of passions in drama, we could gain insight into our own fleeting emotions, which would otherwise be difficult to study directly. The moral purpose of Richardson’s work is evident throughout, as he wanted readers to observe Shakespeare’s depiction of various passions and improve their moral understanding, leading to personal growth and salvation (Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 48).

Richardson also presented a three-fold division of Taste, categorizing it as “feeling,” “discernment,” and “knowledge.” He applied this division to his critique of Shakespeare, suggesting that Shakespeare lacked the last two components. Additionally, Richardson disapproved of what he perceived as inaccuracies, obscure language, vulgarity, and unfair outcomes in Shakespeare’s plays. His classical and conservative perspective found Shakespeare’s tragicomedy and portrayal of important individuals problematic.

Richardson’s criticism had both positive and negative aspects. On the one hand, he was commended for his well-structured arguments, effective use of examples, and occasional genuine appreciation of Shakespeare’s work. On the other hand, Richardson showed little interest in analyzing Shakespeare’s actual texts and lacked historical depth by neglecting to discuss Shakespeare’s sources (Babcock, Jan., 1929).

In summary, Richardson William made significant contributions to the analysis of Shakespeare’s characters, particularly in terms of their moral and psychological aspects. His works garnered both praise and criticism, and his philosophical approach and refined language were notable features of his writings.

Next, we will examine a few examples of the passages Richardson reused the most.

Example 1. ”Upon the sightless couriers of the air, Shall blow the horrid deed in sev’ry eye, That tears shall drown thused”

This is from A philosophical analysis and illustration of some of Shakespeare’s remarkable characters (1784). In this part of the play, Macbeth is thinking about the consequences of his plan to kill King Duncan. He imagines that the news of the murder will spread quickly, like messengers carried by the wind. Everyone will be shocked and horrified by the terrible deed, and there will be so many tears shed that they will overpower even the strongest wind. It shows Macbeth’s realization that his actions will have far-reaching and devastating effects.

Richardson had reused this passage in his writings in a similar context to emphasize the swift and far-reaching dissemination of a shocking or dreadful event. He could have used it to convey the notion that the consequences of this event would be widely known and deeply felt by people, causing great emotional turmoil. Richardson criticizes the characters or situations, highlighting the impact and consequences of their actions.

Example 2. “Stars, hide your fires!

Let not light see my black and deep desire.

One cried, ‘God bless us!’ and the other said, ‘Amen.’

As if they had seen me with the hangman’s hands,

Listening to their fear, I could not say ‘Amen’

When they said, ‘God bless us.’”

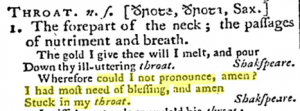

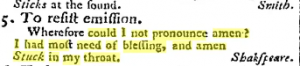

Example 2 was used in Essays on some Shakespeare’s dramatic character (1798). This passage was reused a lot in the dictionary by Samuel Johnson as well. The passage is from Macbeth, specifically act 2, scene 3. It depicts a moment where Macbeth, after assassination of the king, overhears the chamberlains praying and blessing themselves. Macbeth’s guilt and internal turmoil prevent him from saying “Amen” in response to their blessings. Macbeth is expressing his desire for darkness to conceal his wicked intentions. This scene shows Macbeth’s disturbed inability to find peace or seek forgiveness for his actions. Richardson focused on the moral implications and psychological depth portrayed in this scene. He examined Macbeth’s guilt and the internal conflict between his dark desires and the character’s moral decay and the consequences of his actions.

Edward Byyshe

Edward Byyshe (fl. 1702-1712) was an English writer most notably known for his work The Art of English Poetry, first published in 1702, of which successive editions were issued until 1737. In 1714, the second and third parts of this book were published separately under the title The British Parnassus; or a compleat Common Place-book of English Poetry (2 vols.) (Bernard, 2012). These were reissued in 1718 under a new title, The Art of English Poetry, vols. the iiid and ivth. The single Macbeth reuses we have traced can be found in this last work. Though often mocked (British hack writer Charles Gildon called it “a book too scandalously mean to name”), The Art of English Poetry was a largely printed reference book (Bernard, 2012), and it was part of the collections of authors as relevant as Alexander Pope, Samuel Richardson, Henry Fielding, Isaac Watts, Samuel Johnson, and William Blake (Bernard, 2012).

The Art of English Poetry was composed of three sections: the “Rules”, “A Dictionary” and “A Collection”. This last part, also included in The British Parnassus, was written following the tradition of the commonplace book. “Commonplacing”, or the ordering of extracts under headwords, was an habitual tool for the organization of knowledge among intellectuals. However, Byyshe was innovative in the sense that he was the first to transition the genre from “the coterie closet” and “the schoolroom” into the public sphere and “the domain of polite letters” (Bernard, 2012, p. 118). His work was not aimed at a restricted circle, but to a large readership perhaps unaware of the figure of the author (Bernard, 2012).

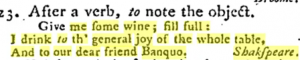

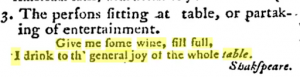

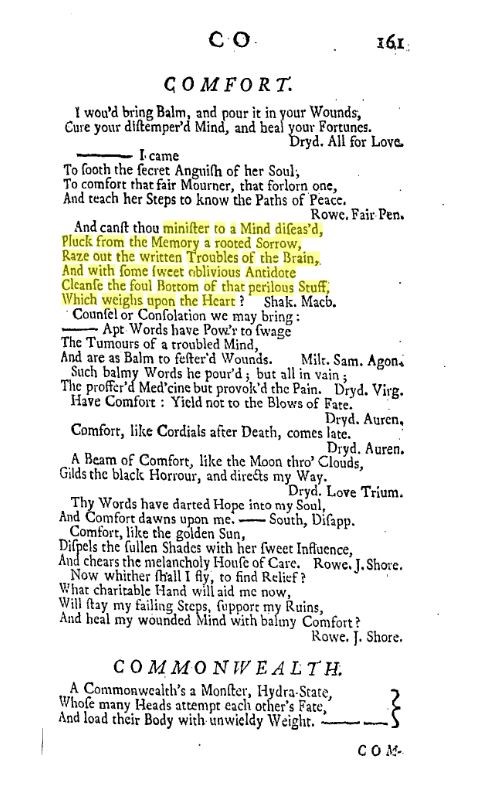

Much like Samuel Johnson used Macbeth passages in his dictionary to illustrate the meaning of words, Byyshe used excerpts of the play to illustrate poetic “Thoughts”, such as “comfort”, “courage”, “dissembling” and “evening”. For instance, the concept of “comfort” is exemplified through the following Macbeth passage from Act V, Scene III:

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?”

Byyshe explains the notion of “comfort” through Macbeth’s plea to the doctor to provide solace for his wife, who was “troubled with thick-coming fancies, / That keep her from her rest”. These lines are, however, so filled with anxiety, that Macbeth seems to be referring to his own distressed mental state, something that the doctor seems to pick up on when he answers using a male pronoun: “Therein the patient / Must minister to himself”.

As seen in this page, Shakespeare’s quote is tucked between John Milton’s tragic closet drama Samson Agonistes (1671) and Nicholas Rowe’s The Fair Penitent (1703), a theatrical adaptation of the tragedy The Fatal Dowry, by Philip Massinger and Nathan Field, which received much praise from, among others (surprise), Samuel Johnson.

Though the influence of The British Parnassus was rarely acknowledged (Bernard, 2012), it is beyond doubt that it was a valuable reference for both writers and the common reader, and that it impacted canon-formation in the 18th century and beyond. Crucially, the transitioning of the commonplace book to a wider readership that Byyshe’s work brought along is a symptom of the change of status of English in relation to Latin which took place in the early 18th century (Bernard, 2012). That Macbeth, and with it Shakespeare, was involved in such a transition is all but irrelevant.

What kinds of passages were reused?

Most reused passages

As we wanted to explore which passages were reused the most, we clustered the passages together by using computational methods. The aim was to see which passage clusters were reused the most and what kinds of topics were discussed in them. Based on the clustered passages, we determined that the three most reused passages in Macbeth are from act 1, scene 3, act 4, scene 1 and act 5, scene 5.

The most reused passage is from act 1, scene 3, and it has been reused 241 times. This passage cluster contains a lot of variation in length: some of the instances are several pages long, while most are only a few lines long. The overall passage cluster refers to Macbeth’s first meeting with the witches. The longer instances are related to collections of plays. During data cleaning, the target texts were filtered by author metadata, but as Macbeth has been published as a part of collections of plays that include plays from multiple authors, these were not excluded from the target data. In addition, the metadata is not comprehensive and therefore some self-references were not excluded. This passage cluster would not, however, be the most reused passage without the shorter instances of the passage although some of the shorter instances do not overlap and thus are not technically reuses of the same passage. 129 instances of the cluster are related to the first prophecy of the witches regarding Macbeth’s ascension to the Scottish throne. This is enough for the passage to remain within the top three of the most reused passages.

The second most reused passage is from act 4, scene 1 and it is an excerpt from the witch’s spells. This passage cluster has been reused 185 times. The third most reused passage is related to Macbeth’s comments about life and time after being informed of his wife’s death. It appears in act 5, scene 5 and its reuse count is 118. Example 1. is an instance of the second most reused passage and an instance of the third cluster is demonstrated in example 2.

Example 1. “Double, double, toil and trouble;

Fire, burn; and caldron bubble”

Example 2. “Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more! It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

Among the topics that seem to be most appealing for authors of the eighteenth century are witches and general comments about universal topics. The top two passage clusters are related to the former and the third most reused passage cluster represents the latter. Similarly, among the top ten most reused clusters, most are also related to either of these two overarching topics. Other clusters depict, for example, tumultuous feelings such as sorrow and hope, mental illness, weather and thought processes related to assassination. Based on the top ten most reused passage clusters, the passages with universal topics and witches seem to be appealing for reusing Macbeth.

Reuse passage visualization

Given some preliminary understanding of the reuse passages, we now proceed to visualize the passages in a vector space as mentioned in the methods section:

In this plot, the sizes of the circles correspond to their reuse counts, and, as mentioned, the distance between the circles represent how different the passages are. Immediately, we see some passages as well as some clusters of very similar texts that are very commonly reused. Upon closer inspection of these clusters, we see that they mostly correspond to reuse of parts of the same section in Macbeth. For example, the farthest clusters to the left of the plot mostly correspond to the “To-morrow, to-morrow” segment in Macbeth:

“morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools .

The way to dusty death”.

The passage is reused extensively by Samuel Johsnon and other authors.e.g. “Morrow-morrow” is reused as a slow, tedious passage of time. Samuel referred to this passage to explain the “last syllable of recorded time” to express how time marches on relentlessly as Macbeth conveyed in his monologue after his wife’s death. There are many circles of average sizes corresponding to this passage, signifying that it is commonly reused in many different ways. Similar inferences can be said about the “Double, double…” section to the bottom right corner.

The previous plot is a good visualization of the landscape of Macbeth reuses. However, we can still add much more information to the plot to get a better understanding of the “areas” within this “landscape”. We turn to topic modeling as mentioned in the Methods section.

Topic Modeling

From the topic words generated by the topic modeling process, we produced the following corresponding topic interpretations:

Topic 0: Thane of Cawdor and nobility: The cluster is related to the titles and positions of Macbeth, such as Thane of Cawdor and Glamis, and his future as foretold by the witches.

Topic 1: The dagger scene: This cluster is related to Macbeth’s hallucination of a dagger before he kills King Duncan, representing his inner conflict and guilt.

Topic 2: Witches and prophecies: This cluster is about the witches and their prophecies, as well as their influence on Macbeth and Banquo’s fate.

Topic 3: Ambition and morality: The cluster discusses the struggle between ambition and morality, the consequences of Macbeth’s actions, and his descent into damnation.

Topic 4: The passage of time: This cluster is about the concept of time in the play, and the realization that life is brief and meaningless, like a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Topic 5: Blood and guilt: This cluster is about the recurring theme of blood and guilt, as well as the characters’ attempts to wash away their sins and seek redemption.

Topic 6: Death and violence: This cluster is about the brutal and violent nature of the play, including the slaughter of innocents and the ruthlessness of Macbeth’s actions.

Topic 7: Supernatural elements: This cluster is about the supernatural elements in the play, including the witches and their ability to bend reality and affect the characters’ decisions.

Topic 8: Sleep and conscience: This cluster is about the theme of sleep and its connection to conscience, guilt, and the search for peace and redemption.

Topic 9: Celebration and doom: This cluster is about the contrast between celebration and the impending doom, as the characters are summoned to their fates.

Topic 10: Fear and horror: This cluster is about the overwhelming sense of fear and horror that permeates the play, as the characters confront their darkest desires and actions.

Topic 11: Tyranny and treason: This cluster is about the themes of tyranny and treason, as Macbeth becomes a tyrant and the other characters grapple with loyalty and betrayal.

Topic 12: Names and titles: This cluster is about the importance of names and titles in the play, particularly in relation to power and ambition.

Topic 13: Witchcraft and potions: This cluster is about the witches and their cauldron, where they brew potions and cast spells to manipulate the course of events.

Topic 14: Memory and cleansing: This cluster is about the desire to erase or cleanse the memory of past actions, and the struggle to reconcile one’s actions with one’s conscience.

Topic 15: Love and deception: This cluster is about the complex relationships between characters, particularly the deceptive nature of appearances and the contrast between fair and foul.

Topic 16: Warfare and conflict: This cluster is about the battles and conflicts that take place throughout the play, both on the battlefield and within the characters themselves.

Topic 17: Night and darkness: This cluster is about the motif of night and darkness, symbolizing the characters’ moral ambiguity and the sinister atmosphere of the play.

Topic 18: Charms and enchantments: This cluster is about the various charms and enchantments used by the witches to manipulate the characters and events.

Topic 19: Hospitality and betrayal: This cluster is about the contrast between the outward show of hospitality and the inner treachery and betrayal that permeate the play.

Topic 20: Desire and concealment: This cluster is about the theme of desire and the need to conceal one’s true intentions, particularly in relation to Macbeth’s ambition and his attempts to hide his guilt.

Topic 21: Mortality and suffering: This cluster is about the themes of mortality, suffering, and the transience of human life.

Topic 22: Kingship and power: This cluster is about the concept of kingship, power, and the struggle for the throne, as well as the responsibilities and consequences that come with it.

Topic 23: Poison and betrayal: This cluster is about the motif of poison, both literal and metaphorical, as a representation of betrayal, deceit, and the corrupting influence of ambition and power in the play.

The topics identified in the analysis primarily revolve around various themes related to Macbeth, including characters, actions, emotions, and objects. These topics provide insight into the multifaceted nature of the play, both in a computational and contextual sense. It is interesting to observe that the most frequently reused passages and the themes identified through topic modeling align closely, enhancing the reliability of our analysis. These themes are self-explanatory within the context of Macbeth, highlighting the complexity of the characters and their actions. Notably, the clustered themes on the left side include the concepts of time, fear and horror, the insignificance of life, memory, cleansing of memory, and the struggle to forget the past, as well as the concepts of supernatural elements. These themes align with the most reused passages by authors such as Samuel Johnson, Richardson William, and Edward Byshee, who appear prominently in the list. Additionally, the passage that emerged from the topic modeling analysis, which starts with “morrow-morrow” reflecting the fleeting nature of time, resonates with Samuel Johnson’s usage of it in a similar context. Topics like Warfare and Conflict, Hospitality and Betrayal, Desire and Concealment further contribute to our understanding of Macbeth’s complex story, although they were not identified as the most frequently reused passages.

The central character of Macbeth is undoubtedly shaped by the witches and their prophecies (Topic 2), which ultimately set the play’s tragic course in motion. The supernatural elements (Topic 7) serve to heighten the drama and challenge the characters’ agency, creating an atmosphere of inevitability and helplessness. The witches’ influence on Macbeth and Banquo’s fate reflects the human tendency to seek validation and certainty in the face of the unknown, thus making this theme relatable to audiences across time and culture.

Macbeth’s ambition and morality (Topic 3) lie at the heart of his character’s development. Driven by the witches’ prophecy, Macbeth grapples with his desire for power, ultimately succumbing to the temptation and committing heinous acts, such as the murder of King Duncan. The dagger scene (Topic 1) symbolizes Macbeth’s inner conflict and guilt, foreshadowing his downward spiral into moral decay. As Macbeth’s ambition grows, so too does his capacity for deception and betrayal (Topic 15), which contrasts sharply with his once-noble status as Thane of Cawdor (Topic 0).

The theme of blood and guilt (Topic 5) is inextricably linked to Macbeth’s ambition and violence (Topic 6). His repeated efforts to wash away his sins, like Lady Macbeth’s infamous “out, damned spot!” speech, demonstrate the indelible stain left on their souls by their actions. The desire for memory and cleansing (Topic 14) further highlights the characters’ struggle to reconcile their actions with their conscience, a conflict that remains pertinent in contemporary society.

Kingship and power (Topic 22) are central to the plot, as Macbeth’s ruthless pursuit of the throne reveals the corrupting nature of power and the lengths individuals will go to secure it. His eventual descent into tyranny (Topic 11) showcases the destructive consequences of unchecked ambition and the erosion of moral boundaries. Shakespeare’s portrayal of tyranny and treason serves as a cautionary tale, warning against the dangers of unbridled power.

The passage of time (Topic 4) is a recurring theme in Macbeth, emphasizing the fleeting nature of life and the ultimate insignificance of human actions. Macbeth’s soliloquy, in which he laments that life is “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing,” underscores this theme, reminding audiences of the existential questions that continue to plague humanity.

Fear and horror (Topic 10) permeate the play, both in response to the supernatural elements and the characters’ own capacity for evil. The night and darkness (Topic 17) motif serves to symbolize moral ambiguity and the sinister atmosphere that pervades the play. The prevalence of death and suffering (Topic 21) highlights the tragic nature of the narrative and the inescapable consequences of the characters’ actions.

The contrast between hospitality and betrayal (Topic 19) is another recurring theme, as Macbeth’s initial welcoming of King Duncan gives way to his brutal murder. This juxtaposition underscores the deceptive nature of appearances, a theme that extends to the witches’ famous line, “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” (Topic 15), which encapsulates the play’s exploration of deception, duplicity, and the discrepancy between outward appearances and inner realities.

The concepts of names and titles (Topic 12) in Macbeth serve not only as markers of status and ambition but also as a commentary on the transience and superficiality of power. Despite his status as Thane of Cawdor and later as king, Macbeth’s actions result in his downfall, demonstrating that titles, while significant, cannot shield one from the consequences of their actions.

Witchcraft and potions (Topic 13), charms, and enchantments (Topic 18) are further aspects of the supernatural that underscore the play’s sense of foreboding and manipulate the course of events. These elements, coupled with the themes of poison and betrayal (Topic 23), serve as metaphors for the corrupting influence of ambition and power, underlining the moral decay that accompanies Macbeth’s rise to the throne.

Lastly, the theme of desire and concealment (Topic 20) is central to Macbeth’s character. His ambition, initially hidden beneath a façade of loyalty, gradually becomes apparent as he manipulates and murders to achieve his goals. This theme resonates with audiences, reflecting the universal struggle between personal desires and societal expectations.

Framing in target texts and intertextuality analysis

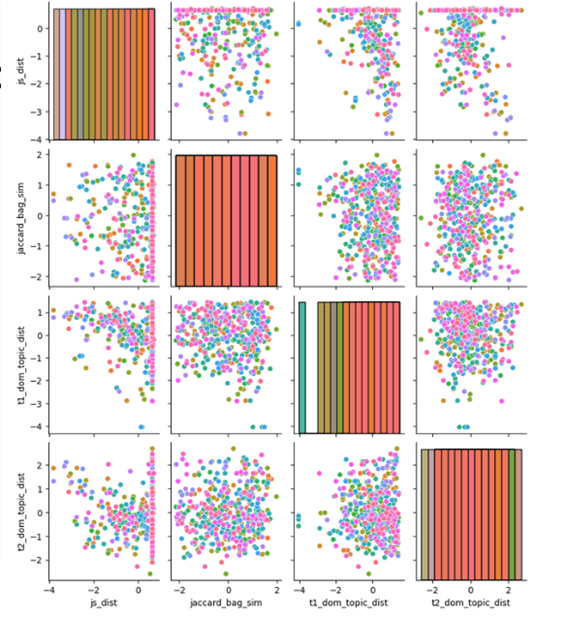

We performed multiple linear regression on three factors of intertextuality to explore the relationship among those. The lexical similarity between the target texts and Macbeth is predicted on a) the topical similarity between the same works and b) the dominant topic of the reuse contexts. The dominant topic of the contexts is a category variable of 50 levels, as we used a 50-topic LDA model as the base of topical similarity measurement. As a result, the regression model shows 0.068 adjusted R-squared (F-value < 0.05), indicating only slight correlation among the reuse contexts’ topics and the lexicon. The weak correlation makes it futile to analyze the individual regression coefficients, therefore we omitted it.

The side-by-side scatter plot below illustrates the relationship among the factors. As we can see, no factor pair shows a “belt”- or “line”-like shape, which matches the result of weak correlation. The topical similarity is highly skewed, meaning the context of all the reuses, regardless of the topic it talks about, is very different from the context of Macbeth. It matches the observation that the reuses are mostly direct quotations, often with explicit mentioning of the origin. Specific examples can be seen in the Methodology section or just below:

In Macbeth, the context is Macbeth’s monologue about how badly he is tortured by the conscientiousness, and the Karma he will get; Topically, it is related to the upper context of A Novel, as it talks about the “complicated enormities… before her mental vision”. However, the lower context talks about the past realities, which encloses the monologue-like imaginations of Karma. From this perspective, we consider it makes sense that most of the reuse works have different contexts in terms of topic.