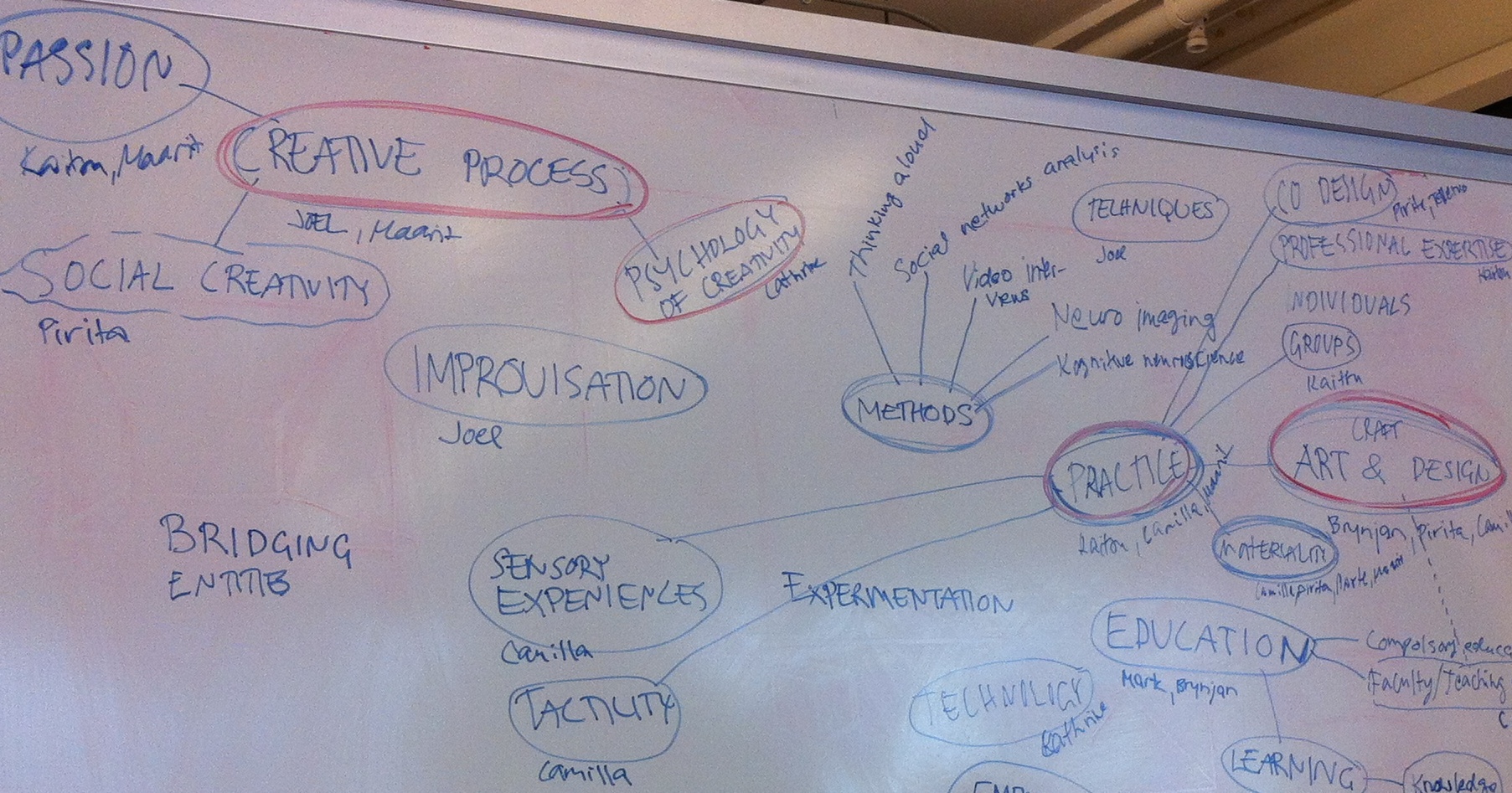

The Handling mind research project aimed to provide a bridge between areas of neuroscience, education and design research – all concerned with embodied activities, social creativity and the extended nature of the human mind. Art, craft and design was understood as a multifaceted activity that involves complex cognitive processes and embodied interaction with materials and tools. This post introduces snapshots on some of our interesting results and provides links to the published doctoral dissertations and research articles.

The Handling mind research project aimed to provide a bridge between areas of neuroscience, education and design research – all concerned with embodied activities, social creativity and the extended nature of the human mind. Art, craft and design was understood as a multifaceted activity that involves complex cognitive processes and embodied interaction with materials and tools. This post introduces snapshots on some of our interesting results and provides links to the published doctoral dissertations and research articles.

Independent clay throwing by deafblind participant after receiving tactile guiding. Images by Camilla Groth.

Camilla Groth

Link to Doctoral study:

Making sense through hands: Design and craft thinking analyzed as embodied cognition

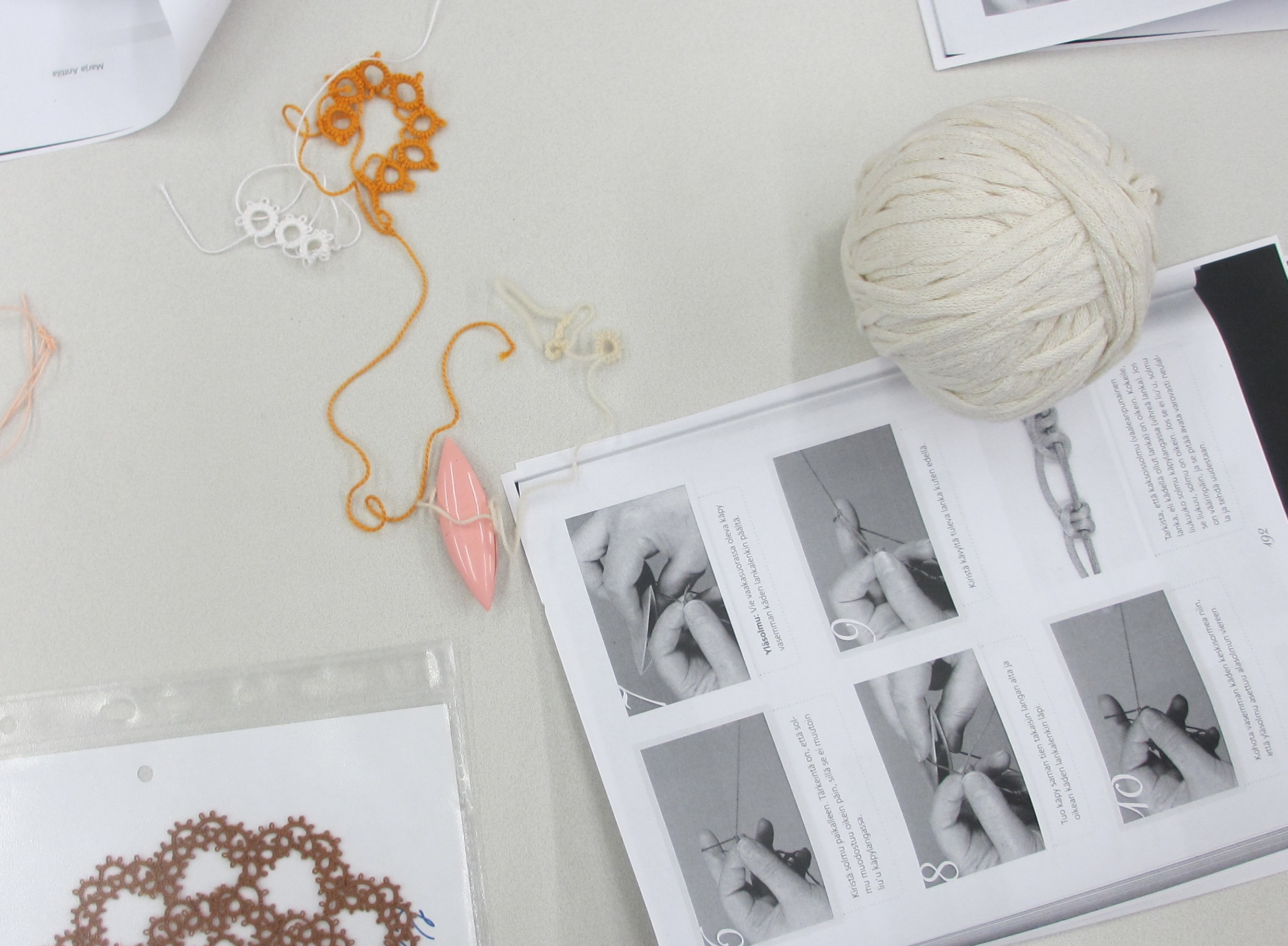

The importance of touch and haptic experiences in decision-making processes and the link to emotions in the context of craft-making was one of the key findings. During the making process, the practitioner seems to gain manual skills and tacit knowledge but also builds herself as a practitioner. Manipulating material could be seen as a way of being in and affecting the world as well as negotiating meaning related to our abilities and limitations. Read more in Tactile augmentation: A multimethod for capturing experiential knowledge.

Many different levels and notions of emotions surfaced through and in connection with haptic experiences. Emotions related to haptic and tactual experiences in a craft-making process affect and regulate risk assessment, decision-making and problem-solving. Moreover, a form of re-knowing of previous knowing aids in overcoming challenges. Read more on Emotions in Risk Assessment and Decision Making Processes.

Touch was an essential evaluation tool for making decisions on materials and for testing materials, but also for communicating ethical and social aspects of the design. Read more on The knowing body in material exploration.

Tactile skills could be taught relying solely on tactile means (omitting verbal and visual means), as the embodied knowledge of the teacher, including exact timing of movements and limb pressure, is more readily available to the student in such a setting. Furthermore, modelling can become an act of making sense (in a similar way as drawing is generally considered) through its capacity to give form and initiate ideas and through its iterative properties. Read more on Making sense: What can we learn from experts of tactile knowledge?

Tarja-Kaarina Laamanen

Link to Doctoral study:

Generating and transforming representations in design ideation

Design ideation is a multimaterial and multimodal process where representations and objects of the material world – important triggers for ideation – inspire and direct the ideation process. Importantly, creative ideation requires gradual development of ideas. Studied design situations required constraining the task in personally meaningful ways. A design situation that started as open was framed by generating and transforming representations, and these intertwined efforts created the dynamic nature of ideation. Read more on Sources of inspiration and mental image in textile design process.

Professional designers had developed strategies of efficiently finding and using sources of inspiration as well as different types of representations for their current cases. Developing a professional vision meant also competence in seeing a common underlying characteristic such as a pattern, a concept, a class membership, a rule, a process or causal relation. The four approaches to ideation, graphic, material, verbal and mental approach illustrated these versatile processes. Read more on Interview Study of Professional Designers’ Ideation Approaches.

Students had to find their own self-imposed constraints in order to manage their design ideation processes. When they did this successfully, they framed the situation in ways that resembled professional designers’ practices. However, novices who did not yet have mature design-thinking capabilities, anchored their process too early to a chosen source of inspiration. Read more on Constraining an open-ended design task by interpreting sources of inspiration.

To conclude, the exploratory process of generating and transforming representations is a holistic making-related activity that is best supported by interaction with peers and different types of externalization methods. In teaching design ideation, deliberate practices and a variety of techniques for generating and transforming representations to develop visual ideas, as well as meaning-making for personal engagement and exploration should be included.

Mimmu Rankanen

Link to Doctoral study:

The visible spectrum: Participants’ experiences of the process and impacts of art therapy

The study focused on clients’ experiences of art therapy process and it’s impacts. A case study described how the changing qualities in the embodied creative art process, in the context of art in therapeutic group, affect the participant’s mental relation to the emotionally problematic issue. The transformative change process proceeded during the creative process from embodied experience into the perception of an alternative meaning.

The quality of aesthetic creative experiences can either hinder or aid a participant’s mental and emotional change processes. In the studied case, the changes from cognitively controlling art-making into a spontaneous and playful approach to art-making – which the client made her way to make art – also affected other levels of her experiences by changing a helpless relationship with a traumatic experience into an agentic position, wherein more flexible observation and experiences of resourcefulness became possible.

Read more on The space between art experiences and reflective understanding in therapy and Clients’ experiences of the impacts of an experiential art therapy group

Contradictions or challenges that are experienced within a therapeutic relationship, group environment or during art processes affect the participants’ experiences of therapeutic change. Interestingly, these experiences can either turn into significant aiding processes and a good outcome or become stagnant and hinder the therapeutic process. Unpleasant emotions that remain unsolved could arise during sensory interaction in art-making or in social interaction, and a fear for others’ interpretations could prevent or restrict expressing personally important issues. The results create a clearer and better structured understanding of how crucial it is for the experienced outcome of art therapy to encounter and reflect those intrapersonal, intermediate and interpersonal experiences, which awake unpleasant emotions during the process.

Artistic interaction that takes place in a group context may include unique therapeutic mechanisms or processes. Any aspect of this intervening interactive relationship between art, participant, therapist and group can either have positive influences or negative influences on the participants’ art therapy process or the outcomes they experience. The results include an overview on how clients described the therapeutic or un-therapeutic effects of art as well as the kinds of positive processes or influences that participants have experienced in relation to art therapy group. Read more on Clients’ positive and negative experiences of experiential art therapy group process and The three-headed girl. The experience of dialogical art therapy viewed from different perspectives.

Tellervo Härkki

Link to Doctoral study:

Handling Knowledge: Three perspectives on embodied creation of knowledge in collaborative design

In collaborative design, students engage in focused knowledge work. On the other hand, collaborative designing can be understood as drafting series of essential features (of the problems and the solutions) in different formats, which build on linguistic and embodied resources.

Sketching has an acknowledged role in facilitating idea generation and communication. In these studies, collaborative sketching was utilized when memorising was required, especially to depict spatial configurations, whereas gestures provided a channel to ideate fine details clearly and with precision by employing both visuospatial and kinaesthetic feedback. Moreover, gestures revealed a conceptualisation that was different from words. A strength of gestures as a resource for creative collaboration is that gestures invite designers to share and communicate rather than withdraw.

Material knowledge was a resource to address the challenges of making, not an end itself. In general, materials were considered to be practical solutions rather than sources of inspiration and new ideas.

In general, the practice of sharing ideas as and when they emerge might benefit novices as much as any single design tool. At best, active and rich use of embodied resources alongside the linguistic ones can turn interaction into inspiraction, that is, interaction that inspires—elicits new ideas and (even) more productive interaction. Further, the epistemic role of the studied embodied resources is not necessarily limited to enriching communication and thinking but could entail the ability to elicit more ideas by enhancing the intensity and richness of collaborative designing.

Read more on Line by line, part by part: Collaborative sketching for designing, Material knowledge in collaborative designing and making – A case of wearable sea creatures and Hands on design: comparing the use of sketching and gesturing in collaborative designing

Maarit Mäkelä

The creative process could be described as altering positions of serendipity and intentionality. Intuitive leaps are taken when circumstances are fortunate or feed the process with opportunities for progress. These paths may be followed or re-wined through an internal, and sometimes shared, learning process that takes time and that benefits from breaks and time for reflection. Materials act as agentic forces and may be attributed partial ownership of the process as they enable or disable certain possibilities through their affordances. Read more on Personal exploration: Serendipity and intentionality as altering positions in a creative process.

Maarit Mäkelä & Teija Löytönen

The physical environment and materials – active agents in the learning process – create a performative learning space. In such a space, learning becomes a more unpredictable and experimental process, opening up new, emergent possibilities. Pedagogical relationships go beyond the teacher and the curriculum, and the agency of materiality has a pedagogical effect. We propose that materiality teaches in its own way, and the design of the learning setting has an important role. Matter can have an unanticipated or unexpected contribution to the learning processes – and to the final artefacts. In addition to the pedagogical agency of matter, physical environment as part of the material world also has agency, thus creating a performative learning space. Instead of contributing solely to transmitting knowledge and skills, the teacher’s role then is to create conditions for the emergent and evolving learning – and to be prepared to learn herself, alongside the students. Read more on Rethinking materialities in higher education.

To sum up four years of intensive work in a blog post is hard

However, we are happy that the goals of the project were achieved very well and we did not drastically change the implementation of the research plan. The project provided a new understanding of the meaning of embodied knowing in relation to material culture. It also revealed new ways to focus future research efforts toward multidisciplinary research. The challenge of the project was to conduct interdisciplinary research creating a mutual language between different discourses (design research and neuroscience). In order to get good quality data in neuroscientific standards we were forced to make compromises in some of the research settings. The strict experimental setting that we had to implement to get our data did not easily capture the essence of the creative design process. Anyhow the discourse was fruitful and we were able to receive meaningful results.

Research setting utilising movement sensors on the wrists and a heartbeat monitor.

Photo by Camilla Groth.

Research setting utilising EEG as well as movement sensors on the wrists and a heartbeat monitor.

Photo by Camilla Groth.

Each of the 30 participants produced 92 pieces of formed clay and 92 drawings, resulting in a room full of ceramic artefacts and drawn designs. Photo by Camilla Groth.

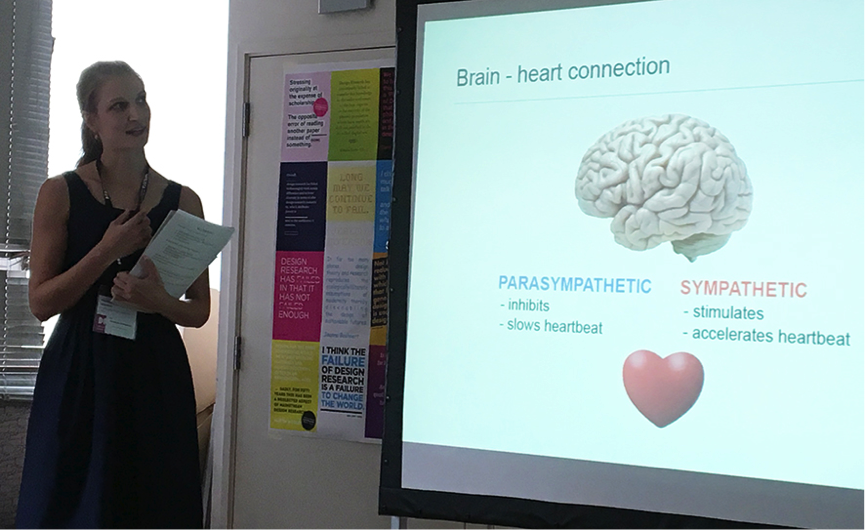

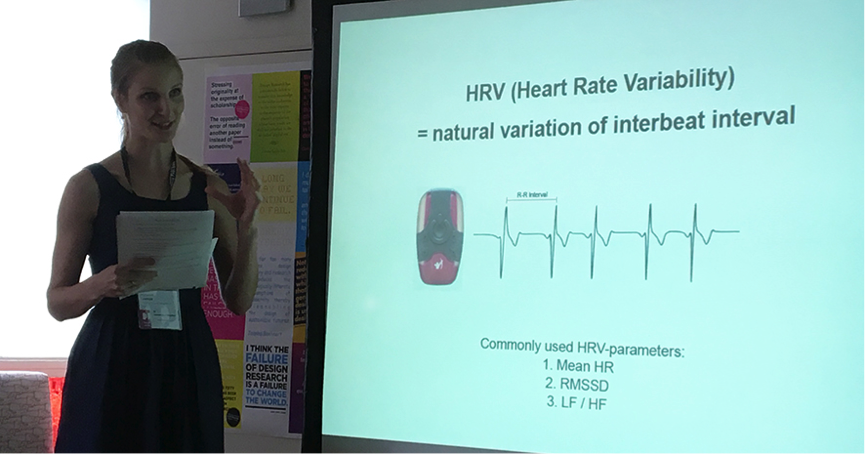

The most challenging task in the project was to design a research setting that would capture the practical information that is relevant to the field of design research, but at the same time acknowledge the limitations of the data that can be acquired via methods used in the field of brain research. The main work related to designing of these methods (Track C) were already done when writing the application, and during the project we were able to implement these study settings to the practice. Thus, in the study we were able to gather the planned data, though in small scale. This means that even though we have results, they are mainly tentative due to the limitations of the gathered data. Regardless, our main contribution to the field is that we opened a neuroscientific track in the field of design research that may be built on by future research teams.

Read more on our neuroscientific studies on

Huotilainen, M., Rankanen, M., Groth, C., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. & Mäkelä, M. (2018) Why our brains love arts and crafts: Implications of creative practices on psychophysical well-being. FORMakademisk Journal, 11 (2).

Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., Huotilainen, M., Mäkelä, M., Groth, C. & Hakkarainen, K. (2016) How can neuroscience help to understand design and craft activity? The promise of cognitive neuroscience in design studies. FORMakademisk, 9 (1) Article 3, 1-16.

Leinikka, M., Huotilainen, M., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., Groth, C., Rankanen, M., Mäkelä, M. (2016) Physiological measurements of drawing and forming activities. In: P. Lloyd & E. Bohemia, eds., Proceedings of Design Research Society Conference 2016, Brighton, Vol. 7, pp. 2941-2957, DOI 10.21606/drs.2016.335

Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., Huotilainen, M., Mäkelä, M. Groth, C. & Hakkarainen, K. (2014) The promise of cognitive neuroscience in design studies. In Lim, Y.-K., Niedderer, K., Redström, J., Stolterman, E., & Valtonen, A. (Eds.). Proceedings of the Design Research Societys’ Conference, Umeå, Sweden: Umeå Institute of Design, Umeå University. pp. 834-846.