The Maker Movement, or Maker Culture was born in the mid 2000s with the publication of the first issue of Make: magazine in 2005 and the first Maker Faire being organised in 2006. Maker Culture differs from regular do-it-yourself activities in three aspects:

- Usage of digital tools

- Cultural norm of sharing plans and co-operating online

- Usage of common planning standards to enable sharing and rapid iteration

Digital tools refer to, for example, 3D printing, laser cutters, and open-source microcontrollers, such as Arduino. Because not everyone has the means to acquire large or expensive equipment, Maker Culture uses shared facilities called hacklabs (also referred to as hackerspace, hackspace, and makerspace). Hacklabs are communal spaces meant for working and aiding other makers, and they are generally not-for-profit.

Makerspaces in the Helsinki area:

Maker Culture in Schools

Playing is a natural way for people to learn. Learning by doing is based on the idea that physical actions bear more likeness to playing, compared to formal classroom teaching. Learning by doing has long been a topic of discussion and it is one reason for why there is interest in Finnish schools to adopt aspects of Maker Culture. Here is an article by Yle on the topic (in Finnish): Maker-kulttuuria tuodaan Suomeenkin – onko tässä koulutuksen uusi suunta?

The underlying theory is Seymour Papert’s Constructionism, which is based on Dewey’s Constructivism. The difference is that in constructionism, the learning happens by building an artefact that is sharable. In Maker Culture, this manifests itself in the production of digital and physical artefacts.

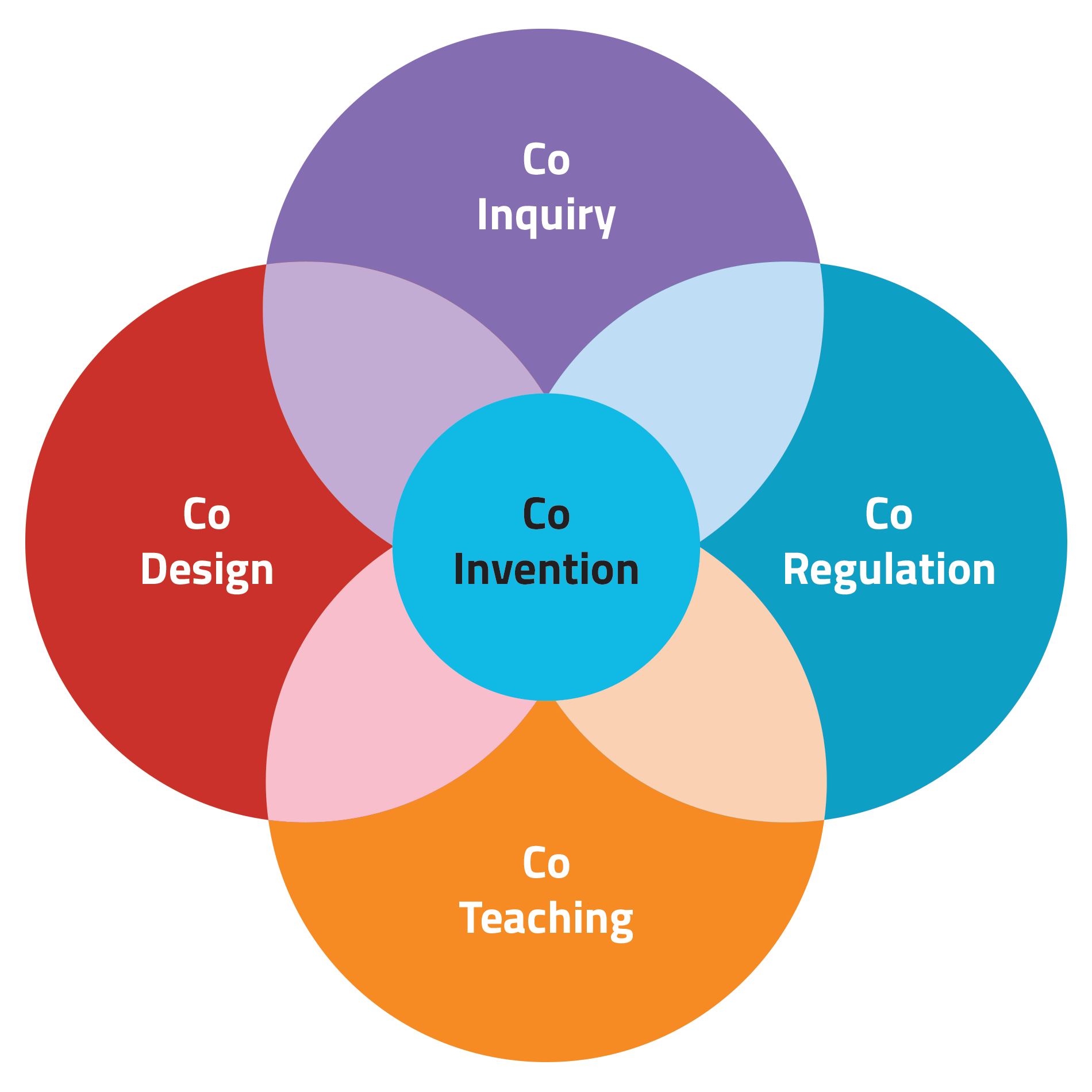

Academic research is also being conducted on the topic of Maker Culture in schools. Helsinki University has launched the Co4Lab project, which “aims at bringing elements of Maker Culture to school by appropriating instruments and methods of digital fabrication and collaborative invention”. The purpose of the project is to research and develop knowledge-creating practices of learning based on co-inquiry. Co-invention in the project consists of four areas:

Learning while doing is not synonymous with education. However, Maker Culture makes attempts to narrow the gap between formal and informal learning and thus forces us to think about learning in a broader and more comprehensive sense. Questions such as “who”, “where”, and “how” can be looked at without getting caught up in strict rules. This fading of boundaries is demonstrated by the fact that Maker Faires are attended by people of all ages and backgrounds, presenting their products and sharing ideas.

There are some structural challenges with bringing Maker Culture into schools. School learning is guided by national and subject-specific curricula and a strong culture of standardisation. Learning by doing is cross-curricular by nature, and a maker project could perhaps function as an integrative learning module, described in the new National Core Curriculum for Basic Education.

Additionally, schools do not necessarily have the opportunity to acquire the digital tools required or to build a hacklab. Schools can, however, make use of existing hacklabs, as well as so called travelling hacklabs.There are also several projects with similar aims, such as these ones by the Innokas Network:

Meanwhile, it should be remembered that although makerspaces include several new and sophisticated technological gadgets, learning should always be focused on the process and the product instead of the tools used.