If social media posts are the measure, it seems that academics working from home have moved from ‘now I have all this extra time’ to ‘I cannot get anything done’ during the first weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown.

I went to ‘I cannot get anything done’ directly.

But, of course, ‘anything’ here refers to writing—that perpetual source of academic bad conscience. I have been reading hundreds of pages of PhD manuscript drafts, MA theses (drafts and assessments), and done six different review jobs (two books, four articles). So, I guess I have done ‘something’. Alas, the writing devil on my shoulder is relentless.

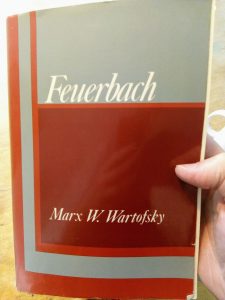

However, in between all this I somehow managed to squeeze in Feuerbach (1977) by Marx W. Wartofsky (check out that first name!) and Ludwig Feuerbach (1967) by Bernard Byhovsky. I read the books in preparation for a course I’m hoping to run one day—for once I started early—and not only did a learn a great deal about the 19th century philosopher, but the act of reading itself forced me to think about the state we are in as scholars. If there is one truism in academia, it is that you cannot develop your own thinking without reading. Unfortunately, the pressure to constantly publish makes writing the ultimate academic achievement. Reading is what one does when all the emails have been answered. But without reading our writing becomes stale and repetitive (I speak from experience here).

So, I was inspired—generally speaking. As a sociologist of religion, less so. For Wartofsky, Feuerbach’s writings on religion are the surface appearance of his philosophical journey from idealism to materialism. Indeed, he considers Feuerbach’s critique of religion in The Essence of Christianity as a ‘manifest’ thesis, underlying which is the ‘latent’ thesis, ‘a radical reinterpretation of philosophy itself’. In his attempt to reinstate Feuerbach as a significant name in the history of philosophy, Wartofsky goes out of his way to downplay the social sources and consequences of Feuerbach’s critique of religion. Methodologically, this means that Feuerbach’s personal history or the social context of his philosophical discoveries plays hardly any role in Wartofsky’s account. His is a philosophical analysis, not intellectual history. It also means that Feuerbach’s critique of religion is treated as an epiphenomenon.

It was fascinating to read Bernard Byhovsky’s CPSU-approved (I assume) portrait of Feuerbach side by side with Wartofsky. For Byhovsky, Feuerbach’s worth is, first and foremost, in paving the way for Marx, Engels, and Lenin. In fact, two of the eight chapters in the book are dedicated to Feuerbach’s legacy. In these, Feuerbach emerges as a ‘pre-materialist’, in the shadow of Marx, who is, predictably, credited with the development of the true ‘science’ of historical/dialectical materialism. The last chapter is dedicated to protecting Feuerbach’s legacy against the later ‘bourgeois’ misrepresentations of his work (including appropriating Feuerbach for theological uses).

So, one book takes a narrow geneaological (Wartofsky calls is the ‘genetic’) approach, and the other one reads Feuerbach teleologically. For Wartofsky, philosophy must be assessed in isolation from Feuerbach’s social or political context. Byhovsky, in turn, moves backwards from official Marxism-Leninism and Soviet atheism to find sources for these in the political-religious struggles of 19th century Germany. Clearly, both present a selective picture.

Reading about Feuerbach in isolation creates an interesting affinity with the man himself. After being denied a career in academia (because of his controversial views on religion), Feuerbach holed up in the village of Bruckberg, removed from collegial university life. His copious Briefwechsel shows that Feuerbach was far from socially isolated, though. He was zooming and emailing away with the technology of his time.

The best bit about collegial meetings—not to mention exchanging actual, thoughtful letters, which I sorely miss—is, I think, the opportunity to learn. There will always be academics who are more interested in being right than listening and learning (mea culpa, I have been one of those people many times), but at its best true conversation can be as enlightening as reading a book like these works on Feuerbach. The good thing about being a professional reader is that you can have an internal conversation. I am not very interested in deciding which one of the Feuerbach portraits is right. It is much more important to understand why each would say what they say.