Author: Marwa Mamdouh-Salem, PhD researcher, Doctoral Programme of Political, Societal and Regional Changes, University of Helsinki.

Critical Issues in Private Higher Education in Egypt: Seeing From the South

Higher Education in Egypt has stuck in transitions, frequently criticized by its inefficiency and modest contribution to graduates’ employability, as well as its modest infrastructure especially in terms of technology and communication. This paper delves deeper into this important sector by examining the impact of private higher institutions PHIs and digitalization. Ever since the Ministry of Higher Education MoHE, the main building bloc in this sector, invited private entrepreneurs to join the landscape in early nineties, little work is conducted to assess the performance of the ‘Newcomer’, however, there are several indications of limited success by private universities to solve the problem. Meanwhile, digitalization has been recently introduced to the universities, including private ones, as part of the government’s policy towards digital transformation, and is spreading rapidly as one of the repercussions of Covid19 pandemic that limited face-to-face education. In addition to virtual learning management systems (ex. Blackboard, Moodle et cetera) Egypt started to embrace other forms of digitalization in the learning process at higher education institutions, though still at preliminary stages.

Keywords: Higher education, edupreneurs, private universities, digitalization, Egypt

Introduction

In an innovative and challenging academic experience, the faculty of Educational Science, University of Helsinki, organized a series of lectures titled ‘FuturEducation: Future Trajectories of Education and the Emergence of Precision Education Governance,’ allowing PhD students to participate in it as part of their doctoral studies. Although my specialization has always been political science, I applied for the course aiming to fill the knowledge gap I have in terms of educational science and pedagogical studies. I have been engaged with the higher education business for six years teaching to freshmen, juniors, seniors and post-grads at the three types of higher education institutions in Egypt, namely public, private and international universities.

Throughout this series of lectures, I have been fluctuating between the four selected topics. Some of the topics sounded familiar such as the ‘role of private entrepreneurships in education’ for Malin Ideland, and to some extent, ‘digitalization and datafication’ for Sam Sellar. My mind has never stopped comparing between and trying to apply what I learnt from the articles and discussions of these two lectures to the situation in Egypt. To the opposite, my attempts to fit the case of Egypt into the other two topics of ‘databanks in education’ for Gita Steiner-Khamsi and the role of ‘cognitive science and neuroscience in education’ for Deborah Youdell seemed as ‘passing a camel through the eye of a needle’. This can be attributed to the fact that Egypt – as a model from the south – is a developing country that has its economic hardships and social challenges. No doubt, the overall political, economic, social, and cultural domestic environment has its impact on the educational and pedagogical sector. Therefore, issues such as datafication, databanks and including cognitive science in the learning process are not on the list of priorities of the competent authorities let alone the fact of being beyond its current capacity. The best way to describe the situation is that if we were to offer a thirsty man all wisdom, we would not please him more than if we gave him a drink. This is, of course, not to suggest that datafication, databanks, using artificial intelligence and cognitive science have no existence whatsoever in the educational landscape in Egypt. What I mean by this is that to the best of my knowledge as university professor, they are not at the core of the educational process or the government policies. I have no idea whether there are plans to include them soon, given the discrete nature of the decision-making process which is monopolized by the executive authority. In other words, policies are enforced from up-to-down and not the opposite which makes it extremely difficult to make predictions on the government’s intention in this regard.

Accordingly, the above-mentioned topics are beyond the scope of this paper which focuses on examining the contribution of private sector and digitalization to higher education in Egypt. In fact, the phenomenon of private higher institutions emerged in early nineties. It is argued that authorizing the establishment of private universities in Egypt coincided with the government’s tendency towards capitalism as it signed an agreement with the IMF according to which a gradual economic reform program was implemented during the 1990s leading to massive privatization process for the public sector and a significant increase of private and foreign direct investment (Dessouki and Korany, 2008). Indeed, this has opened the door for edupreneurs to enter the higher education sector as well. So, although the phenomenon is not that old, however one can claim that twenty-five years of existence is more than enough to examine how private institutions contribute to the higher education in Egypt. Also, it is important to highlight that the analysis in this paper is limited to the universities as it will not include other forms of higher institutions.

As for digitalization, the situation is more difficult since Egypt’s experience towards digital transformation in general, and its application on education, is still at a primary phase. However, day-by-day it gains more momentum because of Covid19 crisis and its negative impact on the face-to-face education. The new and unexpected pandemic situation forced the government and MoHE to accelerate efforts towards including digital transformation into the educational process and to adopt virtual learning methods. At present, software such as Blackboard and Moodle are the mostly used learning management systems which increased the Egyptian PHIs’ reliance on technology in higher education and thus requests more attention from specialists and researchers in educational and pedagogical issues.

Obviously, the issue of higher education in Egypt is quite critical, yet most of the attention is directed to pre-university education. As a result, there is clear scarcity in scientific literature, and even the popular science articles and newspaper chronicles on the it, let alone the sub-topic of the contribution of private universities in the educational landscape. However, this paper is authored by someone who practiced what is written and can, therefore, claim that Egyptian higher educational system is in a critical situation that needs immediate comprehensive treatment. After nearly three decades, private entrepreneurship failed to fill the gap, although the pipeline is filled with other topics such as digitalization, datafication, applying AI, cognitive science et cetera that need to be addressed since they are of equal importance to the educational and pedagogical process if the government of Egypt genuinely wants to enable the educational sector.

Considering the scarcity in documentation on the issue of PHIs in Africa that indeed needs to be treated (Barsoum, 2017a) and the fact that little work is conducted on universities’ digitalization, the reason for the timeliness and relevance of this analysis is that it highlights the following: (a) the fact that the higher educational system in Egypt is the oldest and largest in the region, (b) the vital role of youth in political, economic and social realm in Egypt, (c) the youth unemployment rate is increasing rapidly (15.7 percent), (d) there is a great need to diversify higher education funding, reduce state monopoly on this sector and open for the market for competition, (e) the current level of access to higher education is still at a low level (28 percent) (Barsoum, 2017b).

Finally, the following table introduces some figures relevant to our topic [1]:

| Total Number of Youth (age 18-29) in million | 21.3 |

| Percentage to population | 21% |

| Total Number of Students Enrolled in Universities | 2,838,000 |

| Percentage of Students Enrolled in Private Universities | 22.1% |

| Total Number of University Graduates in 2019 | 456561 |

| Percentage of Private Universities’ Graduates | 6.1% |

Key figures on University Graduates in Egypt (2019)

Problem unsolved: How edupreneurs failed to overcome universities’ crisis in Egypt

In their article Problem unsolved! How edupreneurs enact a school crisis as business possibilities, Ideland et.al (2021) analyze the role of neoliberalization and marketization in education as they highlight the contribution of edupreneurs to better schooling. Inspired by this article, I sought to examine the expanding role of edupreneurs in the higher education sector in Egypt. After further readings I discovered numerous negative consequences that drove me to use the title of Ideland’s article but this time in its negation form. As stated above, Ideland et.al believe that edupreneurs succeeded to present market solutions to the schools’ problems in Sweden, whereas I claim that PHIs in Egypt are struggling to meet the challenges.

Until the end of the twentieth century, the pedagogical realm in Egypt was monopolized by free public universities, except for the American University in Cairo (est. 1919) characterized by high tuition fees that limited the number of applicants to its faculties. Due to the unprecedented increase in the number of students who succeeded to obtain Egyptian Baccalaureate Thanawīyah ‘amah, in addition to other elements that rose the demand on higher education institutions, public universities became unable to provide educational services to all of the baccalaureate’s graduates, whereas the batches doubled its numbers compared to the situation before. Such deficiency opened the door wide for private sector to contribute to the educational sector through inaugurating private universities that offer paid education. After nearly two decades, the current debate is on the effect of these private universities on the educational sector, and some analysts go far beyond that by arguing that neither the public universities nor the private ones have succeeded to improve the quality of higher education in Egypt, besides the failure to foster graduate’s employability.

Barsoum (2017a) emphasized that encouraging private higher education institutions to play a larger role has been one of the key recommendations of international advisers such as the World Bank, which is part of a global trend. She highlights that in his report Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution, Altbach and his colleagues viewed the growth of private higher education around the world as an academic revolution. She also draws the attention to the views of the prominent scholar Martin Trow as he attributes the problem of higher education ‘massification’ resulted in overcrowded lecture halls, deteriorated facilities and outdated library holding. As a result, governments – especially in the developing economies in Africa, Asia and the Middle East – unable deal with these pressures efficiently found the solution through fostering private higher education institutions HEIs. This has been exactly the situation in Egypt where most of the families who belong to the middle and low classes insist to send their children to the university as a mean to secure a satisfactory social and financial class to them in the future. Such high demand put huge pressure on the limited educational budget of the government of Egypt, given the fact the higher education in Egypt is fees-free. This newcomer to the education landscape claimed to be more efficient in preparing graduates of private institutions to meet the job market requirements, and as an effective solution to the challenge of increasing unemployment among fresh graduates in Egypt.

In light of the above-mentioned, the main question is how far the private universities succeeded to solve the problem of higher education in Egypt? Other sub-questions can be raised, such as: To what extent they managed to foster students’ generic academic skills during the undergraduate studies, thus contributed to students’ employability. This section of the paper is organized as follows: a descriptive part on the background of higher education in Egypt and the rise of the phenomenon of private universities followed by an analysis of the main challenges which the PHIs face. These challenges include high tuition fees, government’s restrictions, increasing teaching-space density, insufficient knowledge (‘easy’ education) and low employability.

Background on the evolution of higher education in Egypt

According to Hamoud (2014), Egypt has been the cradle of higher education since the establishment of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, which served as the university in ancient Egypt. Because of its strategic location, Egypt interacted with several peoples in the era that concerns us, such as the Arabs, the Mamluks, the Ottomans, the French and the English, and each of them had an economic, cultural and educational impact on them, especially on higher education. In middle ages, Al-Azhar university which was established in 969AD has played a significant role in fostering higher education in Egypt. Almost a millennium later, Khedive Mohamed Ali (the founder of the modern Egyptian state) launched modern education at the beginning of the nineteenth century as part of a huge modernization project that targeted every sector in the country. By introducing modern educational system – that replicated the western curriculum – Mohamed Ali aimed to serve the greater objective of reintroducing Egypt as an influential regional power, independent enough from the Ottoman empire. In this context, ‘private (higher) education institutions were established according to the European multidisciplinary model,’ stated Hamoud, whereas Egyptian students were sent abroad in scholarships to London, Paris, Rome, Moscow et cetera to get educated and return to Egypt with a satisfactory academic level that allows them to promote national education according to liberal values (Abdelgawad, 2003). The signing of London treaty in 1840 hindered the growth of educational sector in Egypt as it terminated the entire state-building project as part of the West’s plan to curb Mohamed Ali’s regional ambitions.

In the era of the British occupation of Egypt (1882-1952), education witnessed a period of stagnation. The colonial authorities ‘sieged’ higher education as it abolished free education imposing tuition fees. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the national struggle against the British occupation grew, and the attack on its educational policies intensified. In this context, the idea of establishing the national university appeared, and the people spent their own money collecting donations for its establishment. Thus, in 1908, the National University (Al-Gāmi‘ah al-Ahlīyah) began to function, though with limited faculties and incomplete structures (Hamoud, 2014).

The university’s growth continued in connection with the escalation of the national movement against the British occupation, in addition to the role of the Egyptian women’s movement until the national law of establishing the ‘Egyptian University’ was issued. The ‘Egyptian University’ was established in 1925 as the first public university (currently Cairo University). This was followed by the inauguration of several public universities and branches of faculties which were opened in cities that soon became independent universities. The 23rd of July junta/ revolution – that ended the monarchy in 1952 – gave a lot of attention to the issue of free education as an important component of socialism which was adopted by the new political system. Therefore, the number of public universities has increased tremendously during the 1950s, 1960s, and until mid-seventies, as new universities were established in the governorates (Hamoud, 2014).

There are two significant points that are worth highlighting: Firstly, admission to public higher institutions is based on a competition according to the student’s grades obtained in the national baccalaureate. Since 1952, the ‘coordination bureau’ ACBEU (Maktab al-Tansīq) has been responsible to distribute students among universities according to their grades so as priority is for those who scored the higher grades. As a result, faculties of medicine, pharmacy, engineering, economics, political science, and mass communication are dedicated to students of the highest GPA (Magmū‘). Later, this system created higher demand on the PHIs by offering places to the students whom their GPA did not allow them to join the faculties, they wished to study in. Secondly, during the 1960s and 1970s, the Ministry of Manpower (est. 1961) was responsible to hire university graduates in the bureaucracy as soon as the degree is obtained. As a result, the Egyptian bureaucracy has dramatically inflated which resulted in the emergence of the phenomenon of hidden unemployment, until the government was forced in 1990s to terminate such policy of guaranteed employment (Hossni, 2021). The impact of these two points will be examined thoroughly in the coming section on the quality of private higher institutions in Egypt.

As for the evolution of private higher education, it started with the ‘Assiut Faculty, founded in 1865 by the American missionary, and that was followed by the American University in Cairo AUC, which later became the only international private higher educational institution that is not subjected to the supervision of the Egyptian government (Hamoud, 2014). Despite its good academic reputation, enrollment in the American University remained limited to the children of families with high incomes, who can cover the high tuition fees. Private higher institutions remained exclusive to the AUC until 1992 when Law 101 was passed to authorize the establishment of private universities. Accordingly, four new universities opened their doors in 1996, followed by five more in 2000 and six more in 2006. Barsoum and Rashid (2016) stated:

These legal changes marked a shift in the student body of private institutions, opening the door for more achieving students to choose private education. Many of these students opt to private education to study the discipline of their choice, as opposed to being placed in a less desired discipline in public institutions based on their secondary education examination score.

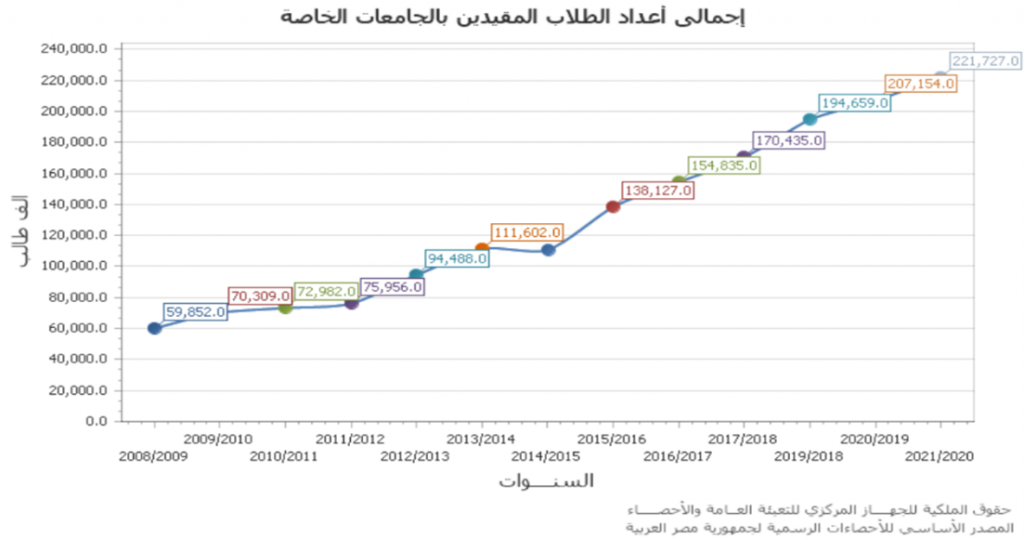

According to recent figures issued by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics CAPMAS, 3.4 million students have been enrolled in higher institutions for the academic year 2020/2021, 221.7 thousand students are enrolled in private universities, representing 6.5 percent of the total number of higher education students in 2020/2021. These figures indicate that despite the significant increase in the number of PHIs in Egypt and the number of students enrolled, however, the quantitative contribution of the private sector to the educational landscape and process is still limited compared to the public sector. Yet, the figure below issued by CAPMAS (2021) on Igmālī A‘dād Al-Tulāb Al-muqaīyadīn bel-gāmi‘āt Al-khāṣah (Total Number of Students Enrolled in Private Universities) the growth emphasizes the dramatic increase in the number of PHIs since its establishment in mid-nineties, which signifies the increased demand on this type of education.

Igmālī A‘dād Al-Tulāb Al-muqaīyadīn bel-gāmi‘āt Al-khāṣah

Igmālī A‘dād Al-Tulāb Al-muqaīyadīn bel-gāmi‘āt Al-khāṣah

(Total Number of Students Enrolled in Private Universities)

(X-axis = academic year/ Y-axis = number of students)

Major challenges for private universities

As it was mentioned in another section of this paper, private higher education has been introduced in early 1990s as a solution for the inability of public universities to meet the rising demand and the increased number of students who have just finished their high school and willing to resume university studies in a way that provides them with high level of job security, in addition to the problem of inefficient teaching methods and lack of facilities. In this context, PHIs in Egypt were supposed to provide students with the following: freedom of choice in terms of studying the discipline they opt to, liberal art education and fostered generic academic skills that enhances their employability. In her article Quality, Pedagogy and Governance in Private Higher Education Institutions in Egypt, Barsoum (2017a) argued that after more than two decades of joining the higher education realm, private universities failed to fill the gap in terms of quantity and quality of graduates.

To begin with, it is useful to highlight that private universities in Egypt are viewed as the last resort for students who ‘… opt to private education to study the discipline of their choice, as opposed to being placed in a less desired discipline in public institutions based on their secondary education examination score,’ stated Barsoum and Rashad (2016). Nevertheless, in his article Private Universities: Education or Exploitation? published by Al-Ahram, the most widely circulating Egyptian national daily newspaper, El-Azab (2015) criticized the high tuition fees of the private universities that make it unaffordable by many households, given the rising economic hardship which the Egyptian middle class has been suffering from for decades. Qassim (2021) draws the attention to the fact that the average annual fee for studying scientific disciplines in the private universities in Egypt ranges between nine to fourteen thousand US dollars, and for humanities it ranges between eleven to thirteen thousand US dollars, whereas per capita GDP in Egypt is about $3,500, according to the World Bank, which is about $10,000 less than the cost of studying for one year at one of these universities.

In fact, the principle of equal opportunity has always been at the core of the Egyptian higher education sector since 1952 and to which the meritocratic admission system to public universities is attributed. Also, according to constitution the right to education is confirmed as article (19) states that ‘every citizen has the right to education,’ whereas article (21) pledges that ‘the State shall allocate a percentage of government spending to university education equivalent to at least 2% of the Gross National Product (GNP), which shall gradually increase to comply with international standards. The State shall encourage the establishment of non-profit, non-governmental universities. The State shall guarantee the quality of education in private and non-governmental universities, ensure that they comply with international quality standards’ (‘Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt’, 2014). This key principle of equal opportunities can no longer be preserved since only the children of the financially capable families could enroll in PHIs, whereas others lack such an alternative even if their scores at high school were higher. Kamal Moghith, education expert stated that these universities target a specific group of the Egyptian society whose income exceeds one million pounds annually, so that they can bear the high cost of studying in private universities (Qassim, 2021).

It is noteworthy that MoHE does not have the authority on PHIs in terms of the tuition fees, as the law regulating private universities in Egypt did not set a percentage to increase expenses annually, and did not specify their value, which makes the matter left without any ceiling and dependent on supply and demand (Qassim, 2021). Barsoum (2017a) presents a plausible diagnosis of the problem:

The legal framework in Egypt does not make a clear distinction between for-profit and not-for-profit institutions. In fact, most private HEIs in Egypt are for-profit institutions. A clear legal foundation for non-profit institutions is an important prerequisite to developing strong private higher education.

Actually, many private universities allocate part of their budget to offer scholarships to students who obtained high scores in their Egyptian Baccalaureate. Nevertheless, these scholarships are not sufficient and there is no possibility to pay the fees in installments. Moreover, private universities continue to raise the tuition fees. For the academic year 2021/2022 there is about thirty percent increase (Hussein, 2021). According to Dr. Mahmoud Fahmy, Secretary of the Council of Private Universities: ‘Tuitions fees are viewed as a red line,’ which indicates that there is no room for financial concessions in this regard (El-Azab, 2015). It is interesting to mention that the Minister of Higher Education Dr. Khaled Abdel-Ghafar has recently stated that increasing the supply through opening more private universities in Egypt will result in a natural decrease of tuition fees (Hosni, 2021).

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that the twenty-six private universities accredited in Egypt act under direct supervision of the Supreme Council of Universities. The Council (est. 1954) is responsible to set the educational policies for the universities, coordinate among them, determine the quality assurance regulations (Hamoud, 2014). As a result, PHIs are subjected to the state-centric approach that enables the Ministry of Higher Education MoHE to monopolize the pedagogy policy decision-making process like the case in public universities. This means that deficiencies similar to that of public higher education is more likely to be detected in PHIs as well (Barsoum, 2017a). The Council has a very strong leverage over PHIs since it the only agency in Egypt that has the authority to equalize the scientific degrees awarded by these institutes. In other words, private universities are forced to abide by the regulations and policies set by the council, otherwise its certificates and academic degrees will not be acknowledged. Although this system provides necessary supervision over private higher education as the universities are held accountable to the council, however it deprives these universities from the right to present pedagogical service, independent from the state’s control. No doubt this adds severe restrictions on the PHIs’ work and limits innovation (‘Al-ta‘līm Al-‘ālī Tuhdir Istiqlālīyit Al-gami‘āt Al-khāṣah (The Ministry of Higher Education Violates the Independence of Private Universities)’, 2015). A stunning example is the restrictions on the freedom of speech during the lectures on the teacher and students specially if the discussion is related to the government and domestic policies.

Turning now to the question of the quality of the learning process. The first point that needs to be underscored is the high teaching space density, a key criticism which public universities have always been subjected to. For example, room sizes averaged 3000 students across all faculty years in the faculties of law and commerce, 1000 students in the faculties of political science and media and 1600 in the faculty of medicine, all of those at Cairo University. So far, the gap is still wide between public and private universities in terms of room density, however, the situation is changing rapidly. At the beginning, students’ numbers for each class in private universities were reasonable. For example, the number of students in political science department at private university X in the academic year 2016/ 2017 has been about thirty students before it quadruples to reach 120 students in 2018/2019 at the same university.[2]

Undoubtedly, there is a negative correlation between the classroom density and the teachers’ performance, as well as the students’ achievements. The more students in class the less efficient teachers can perform, and the less achievements students can do. In the interesting study The Impact of Classroom Density on Teachers’ Performance and Students’ Achievements in Al-Ain School, Al-Manei (2015) underlined the direct link between these elements as he found that decreasing the class density is critical request to guarantee an efficient learning process and went further to suggest that teaching methods, class facilities, technologies integrated must be adapted according to the number of knowledge recipients in class. Similarly, Al-Manei’s argument is stated by other analysts as Chingos and Whitehurst (2011) said that: ‘It appears that very large class-size reductions, on the order of magnitude of 7-10 fewer students per class, can have meaningful long-term effects on student achievement and perhaps on non-cognitive outcomes. The academic effects seem to be largest when introduced in the earliest grades, and for students from less advantaged family backgrounds. They may also be largest in classrooms of teachers who are less well prepared and effective in the classroom.’

Surprisingly, there is not enough literature on the students’ density at the universities compared to that conducted on the preuniversity institutions. However, assumptions like the above-mentioned can be made, of course, with considering the difference in the educational stage, the nature of the curricula, teaching methods, the intended learning outcomes and the assessment methods applied. In private university X, students in a class-size of 120 are expected to achieve lower results in terms of the learnt academic skills and intended learning outcomes compared to those in a class-size of thirty persons. Teachers tend to apply traditional teaching methods – through lecturing – rather than adopting liberal art education that focuses on students’ engagement in class activities such as presentations and open discussions. As a result, in class peer-to-peer assessment remains absent because of the large number of students. On a general level, the entire learning-teaching atmosphere is far away from innovation and efficiency.

Moreover, one of the points of weaknesses of PHIs in Egypt is the quality of knowledge provided. Barsoum (2017b) draws the attention to the fact that most of the private institutions are considered ‘demand-absorbing’ agencies. It performs this role by ‘providing access to students who might not be qualified to join public institutions or who cannot be accommodated due to overcrowding.’ She examined the reflections of some PHIs’ graduates in Egypt on the learning experience they had to find that most of them identified the degree they received and the entire learning process as ‘easy’. Based on the interviews she conducted with PHIs graduates, ‘Easy’ education in private institutions is accepted and commended, Barsoum quotes one of the interviewees:

The institute had no education. Yes, there were good curricula, but how were we taught? Study and memorize for the exam [we are taught]. I had colleagues who used to memorize the programming codes. I had colleagues who could not do a word processing document. All we cared about was what to do for the exam. You ask what exam do we have? … ok, then you memorize and just throw it all up in the exam.

The bitter comment of this graduate demonstrates the ‘no education process’ that dominates the learning process in this private university, however, such incompetent learning system did not prevent the students from getting their credentials and their certificate accredited by the MoHE aiming to find a guaranteed job opportunity based on this accreditation no matter how insufficient the knowledge they gained is. This behavior can be described by the coining phrase ‘diploma disease’, which the outstanding British sociologist Ronald Dore is credited with, referring to the students’ passion to obtain a diploma rather than true and quality learning experience.

Another question that needs to be posed is whether private universities in Egypt increases the employability of graduates? Before we proceed to address this question, it is useful to draw a portrait of the current Egyptian labor market. According to the OECD study titled Schools for Skills – A New Learning Agenda for Egypt (2015), ‘Egypt has a dual economy …. with overlapping formal and informal economic sectors. In 1998, the formal economy was estimated to account for some 60% of total employment, around 40% of which was in the government sector.’ This section focuses on formal sector: in fact, the government plays a significant role in the formal labor market, accounting for 23.7 percent of the employed labor force in 2011 (5.4 million people employed in the government sector). Transformation to capital market economy has reduced the size of the state-owned sector and promoted the role of private sector in terms of job creation. However, economic hardships – especially in the last two years of Covid19 pandemic – hindered private-sector job growth. Accordingly, the official unemployment rate in Egypt jumped to almost 3.4 million out of a work force of 26.8 million, while the actual level of unemployment may be even much higher.

Surprisingly, high rates of unemployment exist among highly educated job seekers. The phenomenon of having excess university graduate supply (particularly in the social science) over labor market demand is referred to by the OECD and the World Bank as ‘educated unemployment’. This can be attributed to the fact that ‘education and training systems are not adequately linked to the skills required by the economy … the skills mismatch between what the labor market offers and what young people expect, continues to grow. Indeed, graduates, misinformed about the country’s working conditions and requirements, have educational profiles that are inconsistent with reality.’ The study underlines the Egyptian employers complain that students were ‘not educated to learn’, ‘lacked initiative’ and had bad work attitudes. Employers look for basic and generic skills to be taught in schools. They want employees who have analytical skills and can use problem-solving techniques, have employability skills such as self-management, the ability to work in a team, communications skills, and the ability to apply numeracy and information technology (IT) skills (OECD, 2015). The UNDP identified the main source the of the problem stating that:

The reality is that neither higher education nor technical and vocational education and training have offered a critical level of skill enhancement that qualifies young people in the search for jobs in the formal economy.

Barsoum and Rashad (2016) underline that private institutions succeeded to increase access to higher education by offering more seats to students. Nevertheless, they failed to provide ‘a qualitatively different education experience that would have an impact on labor market outcomes.’ They attributed this failure to the fact that Egypt’s governance model of private institution is based on the control of education inputs. Instead, it is necessary to adopt policies that focus on education outcomes and set the appropriate measurements to assess them. In Egypt – where there is an excess demand for higher education while competition for quality and innovation take less priority in an eco-system of this nature – it is a necessary to adopt policies that hold PHIs accountable for education and performance.

No more elephants in the room: The long-awaited digital transformation of higher education in Egypt

In their article Becoming information centric: the emergence of new cognitive infrastructures in education policy Sellar and Gulson (2021) explore the emergence of new forms of data-driven decision making in the work of a policy analysis unit ‘The Centre’ within an Australian state education department. On a more general level, this work seeks to increase the use of data infrastructures in educational governance. In other words, it attempts to engage AI in the educational and pedagogical decision-making process. One of the first things that jumped to my mind after reading this amazing article was how advanced is the country that applies such programs in terms of technology and communication facilities, as well as economic and financial capacity. Datafication and digitalization are indeed a demonstration of the country’s development and advancement.

As for Egypt, Moneim (2021) states that the Egyptian government raised investment allocations for the ICT sector by 300 percent in fiscal year 2021/22 in response to the Covid19 circumstances. According to Egypt’s Vision 2030, digital transformation is necessary to align the country with the UN SDGs. In this context, the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology launched ‘Digital Egypt’ project that aim to transform Egypt into a digital society. No doubt the allocation of investments worth $1.6 billion (2018-2020) to improve the internet provision fosters the governments’ efforts towards digital transformation. It is noteworthy that education is one of the targeted sectors to be digitalized according to the government’s digital transformation agenda.

In this context, Bedeir (2020) underlines the importance of digital transformation of university education in Egypt. He lists some early attempts to digitalize Egyptian universities such as the Egyptian Universities Networks (est. 1987) that aimed to enable universities to share resources. Also, the Information and Communication Technology Project that helps the MoHE to manages the educational process using a comprehensive data center. Moreover, the ministry established sixty-two electronic units/ centers in twenty-three universities responsible for converting the courses into electronic form, training faculty members on the use of new technology and automating work in the university libraries. Today, Egypt has been determinant to develop university education and promote the use of technology and artificial intelligence in accordance with the global trend. For example, there is consistent effort to develop the communication infrastructure in several universities to apply electronic exams. Organizing events to promote digital transformation in higher academic institutions, such as the First Higher Education Forum. The forum resulted in the following achievements: (a) SISCO company has pledged to train 106,000 university students every year on information technology programs, (b) establishing three digitalized universities in Cairo, Menofia and Beni Suef, (c) banning the use of the paper book at the university of Mansoura, et cetera. To encourage universities to accelerate digitalization, the Supreme Council of Universities established a prize of ‘Best University’ in terms of digital transformation for the years 2019/2020.

Last summer, the MoHE declared its strategy to digitalize universities in Egypt, as the Minister of higher education, Khaled Abdel Ghafar announced the allocation of 6.2 billion pounds to foster the digitalization of tens of public and private universities. This includes the establishment of smart campus, spreading training programs to universities’ staff, applying electronic exams, launching electronic platforms and portals, applying virtual learning management systems such as Blackboard, Moodle et cetera (Mukhtar, 2021). Obviously, the government and MoFA work to accelerate digitalization in the Egyptian universities, however, it is too early to assess how successful these efforts are given the primacy of the experience.

Conclusion

The status of education is practically deteriorating in Egypt. According to the indicators of the World Economic Forum for 2017, Egypt ranked behind regarding the quality of basic and higher education, a rank that some analysts attributed to the failure of successive Egyptian governments to prioritize education for decades. Studies have shown that more than half of students in Egypt do not meet even the low level in international learning assessments. This paper focused on the university level as it examined the role of private entrepreneurs in promoting quality higher education in Egypt. The line of the analysis pointed out several deficiencies that hinder PHIs from improving education outcomes. Surprisingly, the situation is better in terms of government’s efforts to digitalize universities even though these efforts have been launched recently and accelerated in response to Covid19 restrictions on face-to-face education. In sum, the issues and challenges of higher education in Egypt demonstrate how challenging the situation is in the South. It draws our attention to the wide gap between the developed and the developing nations in terms of their education priorities. This paper did not present solutions to the problem, rather it sought to describe the present and future of higher education in Egypt as seeing from the South.dom

[1] Source: Compiled by author from https://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/2892434.aspx with data originating from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

[2] Source: Numbers compiled by author who taught to these batches by herself at the X University in Egypt in the academic years mentioned in text.

Bibliography

Abdelgawad, G. (2003). Al-tayār al-lībrāli fī Misr fī Maṭla‘ Qarn Gadīd (Liberal Trend in Egypt at the Threshold of a New Century). In Ola Abuzeid (ed.), Al-fikr al-sīyāsi al-Miṣrī al-mu‘āṣir (Egyptian Modern Political Thought), Cairo: Center of Political Research and Studies, 2003, pp. 19-42.

AbdelRashid, H. (2021). Fī Al-yawm al-‘ālmī lil Shabāb Ta‘araf ‘alá Nisbat Al-shabāb fī Miṣr wa-a‘dād Al-ṭulāb fī Maraḥil Al-ta‘līm (In the Occasion of the Youth Day, Get to know the Percentage and Numbers and of Youth and Students in Different Grades in Egypt), Al-Ahram, 12 August 2021. Available at https://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/2892434.aspx (accessed 14 January 2022)

Al-ta‘līm Al-‘ālī Tuhdir Istiqlālīyit Al-gāmi‘āt Al-khāṣah (The Ministry of Higher Education Violates the Independence of Private Universities), Al-Ahram, 5 August 2015.

Barsoum, G. (2017a). Quality, Pedagogy and Governance in Private Higher Education Institutions in Egypt. Africa Education Review, 14 (1), 193-211. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2016.122455

Barsoum, G. (2017b). The allure of ‘easy’: reflections on the learning experience in private higher education institutes in Egypt, Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(1), 105-117. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2016.1153409

Barsoum, G and Rashad, A. (2016). Does Private Higher Education Improve Employment Outcomes? Comparative Analysis from Egypt. Public Organiz Rev. doi: 10.1007/s11115-016-0367-x

Bedeir, E. (2020). Mutaṭalabāt Raqmanit Al-gāmi‘āt Al-Misrīyah fī Daw’ Ba‘ḍ Al-khibrāt Al-‘ālamīyah (The Requirements of Digitalizing Egyptian Universities in Light of International Experiences), Journal of University Performance Development, 12 (1), 267-308.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. (2021). Annual Bulletin of Students Enrolled & Teaching Staff: Higher Education 2020/ 2021.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. Igmālī A‘dād Al-ṭulāb Al-muqaīyadīn bel-gāmi‘āt Al-khāṣah (Total Number of Students Enrolled in Private Universities). Available at https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/IndicatorsPage.aspx?Ind_id=2459 (accessed 8 January 2022).

‘Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt’. 18 January 2014. Available at https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b5368.html (accessed 14 January 2022).

Dessouki, A. and Korany, B. (2008). ‘Regional Leadership: Balancing of Costs and Dividends in the Foreign Policy of Egypt’, in Bahgat Korany & Alei E. Hilal Dessouki (ed.), The Foreign Policy of Arab States: The Challenge of Globalization, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008, pp. 172-173.

El-Azab, W. (2015). Al-gami‘āt Al-khāṣah: Ta‘līm am Istighlāl? (Private Universities: Education or Exploitation?), Al-Ahram, 30 November 2015.

Hamoud, R. (2014). Development of higher education in Egypt: Background paper. In: Quality issues in higher education in the Arab countries: Eighth yearbook, pp. 729-753, 2014. Beirut: Lebanese Association for Educational Studies.

Hosni, A. (2021). Wazir Al-ta‘līm Al-‘ālī: Lā Yūgad fī Al-qānūn Tas‘īr lil-kulīyāt Al-khāṣah fī Miṣr (Minister of Higher Education: Pricing for private Faculties in Egypt is not included in Law), El-Watan, 30 August 2021. Available at https://www.elwatannews.com/news/details/5664907 (accessed 10 January 2022).

Hosni, D. (2021). Sa‘fān: Al-qūwá Al-‘āmilah Tuqaliṣ Dawriha fī Ta‘iyīn Shabāb Al-khirīgīn fī Aghizat Al-dawlah (Safan: The Manpower shrinks its role to appoint fresh graduates in the Bureaucracy), Al-Mal, 12 June 2021.

Hussein, E. (2021). Maṣrufāt Al-gāmi‘āt Al-khāṣah Nar wa-al-a‘lá lil-gami‘āt: Al-qānūn la Yulzimha bi-ḥad Aqṣā (The Tuition Fees of Private Universities is Extremely High, and the Supreme Council says that the law does oblige it to have a Maximum Limit), Akhbar Al-Yawm, 21 August 2021.

Ideland, M., Jobér, A., & Axelsson, T. (2021). Problem solved! How eduprenuers enact a school crisis as business possibilities. European Educational Research Journal, 20(1), 83–101. doi:10.1177/1474904120952978

Mokhtar, H. (2021). Wazīr Al-ta‘līm Al-‘ālī: Raqmanit 27 Gāmi‘ah ḥukumīyah wa-gāmi‘at Al-Azhar bi-taklufat 4.7 Milīyār Gunaīyih (Minister of Higher Education: Digitalizing 27 Public Universities and Al-Azhar Universities at the Cost of 4.7 Billion Pounds), Al-Yawm Al-Sabi‘, 13 August 2021.

Moneim, D. (2021). Digital transformation: Egypt’s means to build back better, Ahram Online, 7 August 2021. Available on https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/418543/Business/Economy/Digital-transformation-Egypt%E2%80%99s-means-to-build-back.aspx (accessed 15 January 2022).

OECD. (2015). Schools for Skills a New Learning Agenda for Egypt. Available at https://www.oecd.org/countries/egypt/Schools-for-skills-a-new-learning-agenda-for-Egypt.pdf

Qassim, N. (2021). Al- Gami‘āt Al-khāṣah wa-al-agnabīyah fī Miṣr: Man Yastaṭī‘ Taḥamul Al-rusūm Al-bāhizah? (Private and Foreign Universities in Egypt: Who can bear the Expensive Fees?), BBC News, 4 September 2021. Available at https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast-58397557 (accessed 14 January 2022).

Ragab, A. (2021). Al-gāmi‘at Al-khāṣa fī Miṣr ṭawq Al-nagāh Rughm Irtifā‘ As‘āriha (Private Universities in Egypt is the Life Savior albeit its Hight Tuition Fees), Sky News Arabiya, 31 August 2021.

Salem, S. (2015). The Impact of Classroom Density on teachers’ Performance and Students’ Achievement in Al-Ain School: Perspective of Teachers and Students. Theses. 42. Available at https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/all_theses/42 (accessed 13 January 2022).

Supreme Council of Universities. Nabza ‘an Al-Maglis (About the Council). Available at https://scu.eg/News/259# (accessed 9 January 2022).

Trow, M. (2006). “Reflections on the Transition from Elite to Mass to Universal Access: Forms and Phases of Higher Education in Modern Societies since WWII.” In International Handbook of Higher Education, edited by J. J. F. Forest and P. G. Altbach, 243–280. Dordrecht: Springer.

Whitehurst, G. and Chingos, M. (2011). Class Size: What Research Says and What it Means for State Policy. Brown Center on Education Policy. 11 May 2011. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/class-size-what-research-says-and-what-it-means-for-state-policy/ (accessed 13 January 2022).

Acknowledgement: I owe deep gratitude to Professor Ghada Barsoum, Chair of the Department of Public Policy and Administration at the American University in Cairo (AUC), for providing the most valuable insights and for sharing her work, time, and thoughts on private higher education in Egypt with me.