By Eugenia Pesci, doctoral researcher in the Horizon 2020 MSCA ITN Markets project, Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, Finland.

Photos by Eugenia Pesci, Giulio Benedetti and Tommaso Aguzzi.

On 26 November – 3 December, thirteen early-stage researchers of the International Training Network Markets (MSCA ITN Markets), funded by the Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska Curie Actions, were hosted by one of the ITN partners – the Center for Social Sciences (CSS) in Tbilisi, Georgia, for the second in-person project meeting. The five-day program included fellows’ presentations of their research progress, brainstorming on the concept of informality, a workshop on grant proposal writing, and three training sessions on both qualitative and quantitative research methods. The program was enriched by a visit to the Georgian Parliament, Q&A sessions with two Georgian politicians and a think tank expert to have a better understanding of the country’s current political situation, in particular vis-à-vis Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and its domestic spillover effects. During our visit to the Parliament, we met with the Deputy Chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, MP Giorgi Khalashvili of the ruling Georgian Dream faction. He highlighted Georgia’s difficult position as a small state, especially in a situation when the international rules-based order has been turned upside down by the war in Ukraine. Georgia did not join the Western sanctions against Russia and did not send weapons to Ukraine, though it continues providing humanitarian help and hosting Ukrainian refugees inside Georgia. The opposition and ordinary citizens have been criticizing the ambiguous position of the Georgian Dream-led government vis-à-vis Russia’s aggression and have been demanding more concrete actions against Russia, like introducing a visa regime to limit the inflow of Russians citizens fleeing mobilization.

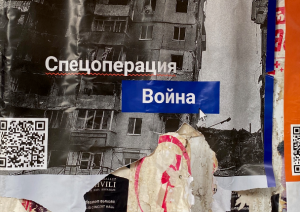

Although talking to politicians and experts of international politics was eye opening for grasping the current political mood in the country, what really interested me was to observe how everyday life is being affected by the war in Ukraine and what people think about the situation. Walking around Tbilisi, it was impossible not to notice the abundance of anti-Russian slogans on the walls, the omnipresence of Ukrainian flags, as well as anti-propaganda campaigns addressed at Russian speakers. In Tbilisi, street walls, shop windows, bars and cafes have become a space where ordinary people engage in political debates, express their support for Ukraine, their condemnation of Putin’s regime, and irritation towards Russian ‘relocants’ (relokanty). The mass inflow of Russians after the announcement of the partial mobilization in September provoked an unprecedented housing crisis, with cases of tenants being evicted or ‘encouraged’ to move out because of the sudden increase of their rents.

A friend living in Tbilisi told me her rent went from an initial 400 US dollars to 800. Now that the contract needs to be renewed, the owner is asking for one thousand US dollars, an exorbitant sum for a one-room flat in Tbilisi. Property owners are confident they will find middle-class Russians willing to rent the flat at such price. In the old town quarter, fancy restaurants and hipster cafés with European prices – unaffordable for the majority of the local population – have popped up with the arrival of Russian digital nomads. According to official estimates, around 100 thousand Russian citizens arrived to Georgia since the beginning of the war, which corresponds to 3 percent of the country’s total population. In February and March, it was mostly members of the opposition and the ‘creative class’ from Moscow and Saint Petersburg who moved to Georgia because of their anti-war position. However, after the announcement of the ‘partial mobilization’ on 21 September, many ordinary Russians, even those who supported Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, decided to leave the country almost overnight to avoid the front.

The presence of young Russians in Tbilisi hardly goes unnoticed even at night, when outside the most popular bars and clubs of the capital you can hardly hear speaking Georgian. At a jazz bar in one of the central streets, a waiter gets annoyed when someone asks for the bill in a mix of English and Russian. “We do not speak Russian here”, she replies in English. Not everyone seems to appreciate that Russians feel ‘too much at home’ in Tbilisi. The question of which language to use when addressing someone in the street acquires new meanings under the current circumstances. When I sat on a taxi at the airport, the driver, a young man in his thirties – asked me in Russian where I was from. When I told him I am Italian, he started laughing and said: “It can’t be! You are Russian; I can see it from your face! Now all Russians say like that, that they come from other countries… I met many of you, you all pretend to come from another country, you do not want to say you are Russian!”.

The massive arrival of Russians is having a visible impact on Georgia’s economy, from inflation to the dramatic rise in rent prices. Besides the negative consequences, the National Bank of Georgia predicted that the arrival of Russians would contribute to an additional 500 million US dollars to the Georgian economy, revitalizing the tourism sector after two years of crisis due to the pandemic.

Even if this is true, the economic benefits of this consumption boost remain concentrated in the housing and service sectors of Tbilisi and Batumi, thus mostly benefiting business owners and the rentier class, leaving the majority of the ordinary people to cope with impoverishment and a shrinking labour market. Recent surveys show that more than 70 percent of Georgians are worried about unemployment and the rising living costs due inflation. By the end of 2022, average monthly earnings amounted 595 US dollars, though if we look at the median earnings provided by the National Statistics Committee of Georgia, wages are just above 330 US dollars. In 2021, unemployment rate surpassed 20 percent; by the end of 2022, despite the post-Covid recovery, it remained high at 15 percent. The situation is particularly grim for young people, as more than 34 percent of those aged 15-29 is considered to be not in employment, education or training (NEET). The lack of a stable employment and the impossibility to provide households for basic needs pushes many Georgians to seek employment abroad. Even if the streets of Tbilisi reflected quite well the overall mood in Georgia, I wanted to see how people leave in less isolated areas outside of the capital.

Together with other ITN Market fellows, I decided to embark on a three-day trip to the Pankisi Gorge, a three-hour ride from Tbilisi. It is a 20-km long valley in the Georgian region of Kakheti, near the border with the Russian Federation. The valley, which nowadays counts around 5 thousand inhabitants residing in a handful of villages, is home to the Kists, an ethnic group originating from the Chechens of the northern Caucasus. Our first stop was Akhmeta, the municipal center and entrance point to the valley. From there, wel planned to take a taxi and to visit the Kist villages of Jokolo and Duisi, home to ancient mosques. On our way, we decided to call our host in the village of Jokolo to inform her of our arrival time. We booked the place through a popular platform for short-term homestays and paid the entire sum in advance. To our surprise, the host said there was a mistake and that the guesthouse was closed. We tried to call other guesthouses, but they were all closed for the winter, a dead seasons for tourism in this rather isolated area. After many unsuccessful phone calls, we found a guesthouse in Akhmeta that agreed to host us. Our host Cicino, an old Georgian woman, spent more than 20 years working in Moscow and recently returned to her native village. Their children and grandchildren all live abroad or in the capital Tbilisi. She said we were lucky to find her there, and even though she admitted that heating the house only for us would cost her a lot, she agreed to switch on the heating in our rooms and in the bathroom. Though very polite, Cicino seemed a bit suspicious about our questions regarding the Pankisi gorge and even seemed offended when we asked whether there were ethnic Chechens in Akhmeta: “Why are you asking such questions? Why are you interested in that?”.

The next day, on our way to the village of Duisi, we walked past what seemed from the outside an abandoned hospital building. The building now hosts an ethnographic museum, the headquarters of Radio Pankisi, and an English language school. The museum turned out to be closed. An old woman living in the other wing of the building, noticing our surprise in finding the museum closed, took her address book and gave us the phone number of the museum director. After receiving no answer, we thanked the old woman and decide to come back on the next day. While were deciding what to do, a group of girls from the second floor was staring at us with curiosity. They had just attended an English language class at the one of Roddy’s Scoot Foundation schools, a charity named after Roddy Scott, a BBC journalist killed during the second Chechen war. The foundation teaches English to over 270 students from the entire valley. Besides English classes and judo lessons, there are very few activities that children in the valley can do.

While we were looking for the building of the ancient mosque in the village of Duisi, we run into a group of schoolchildren. When I asked them what language did they speak, one of them answered me in Russian: “we are Chechens, we speak Chechen at home but we learn Georgian at school. We come here to learn English, when we have nothing else to do”. The recent history of the Pankisi gorge has been shaped by the two Chechen wars in the neighboring Russian Federation, when the valley had the reputation of being a transit point for drug traffickers and arms smugglers to Chechen separatists. During the second Chechen war, the gorge became a crossing point for foreign fighters from the Middle East who wanted to join the Chechen separatists. In the early 2000’s, Russia claimed that Chechen armed groups were hiding in Pankisi and were using the mountain passes around the valley to return to Chechnya and carry out terrorist activities across Russia. In 2001 and 2002, Russia repeatedly bombed the gorge. Even though the Georgian government conducted an anti-terrorist operation after this episode, it did not put enough resources to improve the socio-economic situation in the region.

Almost everyone we spoke to in the valley said the biggest problem was unemployment and the lack of education and career perspectives for young people. Over the last 20 years, the population in the valley has been steadily decreasing, as work-age population moves to other regions of Georgia or to Russia. Since 2017, when the EU introduced a visa-free regime with Georgia, countries like Italy and Germany are becoming increasingly popular destinations for labour migrants. In Pankisi, we met a couple of taxi drivers whose wives work in Italy as caretakers for the elderly. There are also those who see the recent tourism development as a chance to come back and open their own business. The owner of a hotel under construction in Akhmeta told us she came back from Israel after seven years and decided to invest her savings in the tourist sector. She proudly shows us the brand new hotel rooms and hopes the summer season will be a success.

Only a decade ago, rampant unemployment and the lack of perspectives were among the reasons that led many Kist young men to join Islamist groups and travel to Syria to join ISIS, although the exact number is still unknown. Today, tourism and labour migration are seen by many locals as the only options to get out of poverty. Thanks to local initiatives for community development, the Pankisi gorge is an increasingly popular spot for hiking in the Tusheti mountain range. In summer, dozens of guesthouses in Pankisi’s villages of Jokolo and Duisi welcome tourists from all over the world. However, as our first-hand experience has taught us, tourism in Pankisi is a seasonal thing. In winter, those working in the tourist industry close their activities and move to Tbilisi to find temporary employment there. Others rely on remittances. According to recent data, Georgia’s remittances from EU countries, in particular from Italy, where caretakers are in high demand, have been steadily rising. Remittances are boosting domestic consumption and contributing to the country’s overall economic growth, but they are also emptying out villages and contributing to the rising of inequality. Though being quite short, our visit to the Pankisi Gorge opened us another Georgia that we did not know almost anything about, where the wounds from a recent past are still shaping its present.

The second in-person ITN Markets meeting was not only an occasion to engage in academic conversations and improve our research skills; it gave us the possibility to get acquainted with Georgian politics and to see with our eyes the spillover effects of the war in Ukraine and the many contradictions that characterize Georgian society. It was also an occasion to delve into Georgia’s recent history, ethnic and religious diversity, and cultural richness.