02.12.2015 Eeva-Liisa Bastman

November and December are dark times in the North. During the Finnish kaamos, the dark winter period, we only have few hours of daylight. Night closes in earlier and earlier, and we do what we can to keep the gloominess away.

Taking into account the seemingly endless hours of darkness, it is easy to understand why light and lighting are such central elements in the Finnish Christmas preparations. By the end of November, candles, lanterns and Christmas lights in all colours and shapes turn up everywhere. Artificial lighting cannot compensate for the lack of natural light, but it does brighten up the darkness a bit. Christmas lightings remind us that eventually, days will grow longer again. Symbolically, in a Christian context, the approaching light is associated with the advent of Christ. In a way, the habit of lighting Christmas lightings can be seen as a way to reenact the prophecy about the people who walk in darkness and the light that shall shine upon them (Isaiah 9:2).

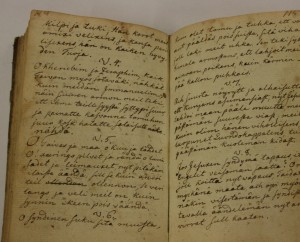

As I come across a Christmas hymn in a hand-written hymnal from the 1780s in the Literary archives of the Finnish Literature Society, I find myself thinking about Christmas times in the 1780s compared to the present days. If the darkness seems overwhelming for us, despite of all the street lights and led lights and the big and small gleaming screens we constantly keep peering at, how dark has the darkness been for people living before the invention of electric light?

The small hymn book has presumably been compiled and used by pietists in the Southern Finnish town of Orimattila, but much of its history remains to be unearthed. Many of the hymns, meticulously written down in small but readable handwriting, are not well known: some were never printed and are nowadays completely forgotten. The only Christmas hymn in the book is written by Gustaf Lilius – his name, Gus. Lilius, can be found at the bottom of the page – but of this person nothing is known. Who was he, and did he have a personal connection with the pietists in Orimattila? How did his hymn end up in the manuscript? Was it sung to lighten up the long dark nights before Christmas, and if so, by whom?

For the speaker of the poem, the birth of Christ seems to bring the world into a state of transformation. Instead of the normal winter weather with rain, sleet or snow, the hymn describes how the “righteous sun” shines (“Vanhurskas auring nyt paistapi”) and how the heaven is dripping grace (“taivas armoa tiukupi”) as people in the “Finnish marchlands” (“Suomen saaren soilla”) come together to celebrate Christmas.

Light is a central motif in many Christmas hymns and we encounter it in Gustaf Lilius’ hymn as well. Here, light is associated with Jesus who is described both as the sweet new-born child lying on the straw but also as the creator, the ruler and the redeemer, who overrides death and brings with him a dawn that shines brighter than the sun (“kirkamb on auringon valo”). The speaker of the poem urges everyone to join in a resounding song of praise that resonates all the way to “the house of heavens”:

Se lapsi nyt pahnoisa kärittele

jong taivas on istuma Jalo

se koito nyt meitä jäll etsiskele

kuin kirkamb on auringon valo

sijs kitosta hälle huutakam

ja ylistys korkja veisatkam

ett kaikupi Taivahan talon.

(KIA A1663 25:2)

(The child lies on the straw/ and heaven is his noble throne./ We are again sought after by the dawn that shines brighter than the Sun./ Therefore, let us shout out our thanks/ and sing high praises/ that resonate to the house of heavens.)

The linkage of light to hope and gladness is not only typical for Christmas hymns or even hymns in general, the symbolic meaning is more universal. Perhaps a more genre specific motif, also found in Gustaf Lilius’ hymn, is singing. Motifs connected to singing and music are frequently used to represent joy and gratitude, and hymns describing or expressing praise and adoration very often explicitly refer to the actual act of singing hymns.

A central element in Lilius’ Christmas hymn is the exhortation to join in the singing. Here, the speaker refers to the heavenly host that praises God with their Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men (Luke 2:14). Even if it is not stated that the praise of the angels is a song, the gloria is usually perceived as one. In this hymn, the song of the angels is set forth as an example for the world to follow. When the birth of Jesus makes even the angels sing, says the speaker, then how can the world, liberated from the pains of death, be silent?

Jos JEsuxen syndymä tapaus

its Engelit veisaman saatta.

O maa joll koitta nyt wapaus,

taidatkos myckänä maata.

Ah opi myös sinäkin visertämän

ja syndisten tavalla äändelemän

nyt armon virrat sull kaatan.

(KIA A1663, 25:8)

(If the birth of Jesus/ makes the angels sing/ then how can you, O world, at the brake of freedom/stay mute?/ Oh, you too should learn to twitter/ and to make sounds, like the sinners/ as the streams of grace are poured to you.)

Here, the ‘world’ is being addressed as ‘you’, and the speaker proposes that the world should learn to ‘twitter like the sinners’. The twittering draws parallels between humans and birds suggesting that people should express their joy in singing. Moreover, with the chirping and trilling of birds, the sound world of spring as well as the growing light that inspires birds to sing, enters the hymn. The contrast between the quiet and dusky winter landscape and the animate sounds and colours of spring is further enhanced, when the speaker urges other natural beings to join the chorus.

The speaker repeatedly addresses not only the world and us, his audience, but also the heaven and the earth, the cherubs and seraphs, the moon, the stars, the sun and even clouds, sleet, snowfall and lightning:

O Taivas ja maa, o kuu ja tähdet

O! auringo pilvet ja rändä

o lumisade ja leimauxet

nyt pitäkäm iloista äändä

sill se kuin andoi teil olennon,

se werilango ja veli meil on

kuin synnin ikeen pois väändä.

(KIA A1663, 25:5)

(O Heaven and e arth, o moon and stars/ O! Sun, clouds and sleet/ o snowfall and lightning/ let us make joyful noises/ he who gave you your substance/ is our brother and brother-in-law in blood/ and he takes away the yoke of sin.)

A similar record of natural forces can be found in an older Christmas hymn in the hymnal of the Evangelic Lutheran Church from 1701, translated from Latin by Finnish baroque hymn poet Hemminki Maskulainen:

Meill’ taivaan korkia Kuningas

Neitseest’ nuorest’ puhtaast’

Syntyi ihmiseks’,

syntyi ihmiseks’.

Kuta kuu, ilma, aurinko

Maa, meri, tähdet, taivaat

Ain’ palvelevat,

ain’ palvelevat.

(VVK 1701, 126: 1-2).

(For us, the high King of heaven/ by a young pure virgin/ was born as man.

Whom the moon, the air, the Sun/ the earth, sea, stars and heaven/ always serve.)

The difference here compared to the Christmas hymn in the Orimattila manuscript has to do with manner of representation. Maskulainen’s hymn describes to us how the moon, the air, the sun, the earth, the sea, the stars and heavens serve the Lord. In Lilius’ hymn, the elements are being directly addressed: the heaven and earth, the moon and the sun are the ones being spoken to: “O Heaven and earth, o moon and stars/ O! Sun, clouds and sleet” (“O Taivas ja maa, o kuu ja tähdet, O! auringo pilvet ja rändä”).

This apostrophic gesture – the act of addressing someone or something that is not present, like the sun and the moon – is ritualistic, performative and distinctively poetical, according to Jonathan Culler (2015, 213). Culler writes that the “function of apostrophe would be to posit a potentially responsive or at least attentive universe, to which one has a relation.” (Culler 2015, 216). The addressing of cherubs and seraphs or stars, snowfall and lightning means that they are represented as beings the speaker can communicate with. The apostrophe personifies them into creatures that hear, listen, and possibly respond by doing what the speaker of the poem asks them to do: to make “joyous noises” (“iloista äändä”).

Thus, the act of apostrophizing endows the speaker with almost shamanistic powers. Like Orpheus or Väinämöinen he makes the natural forces and the heavenly creatures as well as the earthly ones stay and listen to himself. But unlike these mythical singers, whose music quietens down all living beings, the speaker in Lilius’ Christmas hymn makes the entire creation sing together with him to celebrate the birth of Christ. As a genre of religious poetry as well as a genre of congregational singing, the hymn seems to offer a suitable format for the staging of this joyous singalong of cosmic proportions. And so, with the help of the poetic power of the apostrophe, the silent, dark Finnish midwinter suddenly brakes into luminous song.

Gustaf Lilius’ Christmas hymn in the Orimattila Manuscript (A1663), a handwritten hymn book, in the Literary Archives of the Finnish Literature Society.

References:

- Culler, Jonathan 2015: Theory of the Lyric. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Orimattilan käsikirjoitus: Laulu ja virsikokoelma, käsinkirjoitettu SKS/KIA A1663. Kirjallisuusarkisto, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. The Orimattila Manuscript, Literary Archives, Finnish Literature Society, SKS/KIA A1663

- Väinölä, Tauno 1995: Vanha Virsikirja. Vuoden 1701 suomalainen virsikirja. Tauno Väinölä. Helsinki: Kirjaneliö.