HISTORY | ARCHIVE | LOGO GALLERY

How it all began

Unlike the name suggests, the very first Spring Symposium was not held in the spring, but in November 1990 at Tvärminne Zoological Station, south coast of Finland, within the former Department of Zoology. Originally an environmental seminar was organized were, many post-graduate students gave talks and a competition for the best talk was arranged. This laid the basis for the annual student symposium that was officially started a year later.

On this very first occasion Ilkka Teräs, a former Departmental Coordinator of the University, was acting as the secretary of the meeting, while the professors and supervisors acted as evaluators. The winner of the best talk was a PhD student Jari Heikkilä, currently working as a Senior Researcher in the Finnish Environment Institute. Jari presented his research plan about the interactions between voles and small Mustelids on the islands of Lake Inarijärvi. His work was developed under the supervision of Ilkka Hanski . The prize for the winner was decided during the bus trip back to Helsinki as a sum of money to buy a laptop computer.

When Teräs analyzed the votes later, he pointed out that it would be wise to use independent evaluators to get neutral opinions, and thereafter the evaluators came from outside the department, in most cases from abroad. The idea of inviting external evaluators to judge the presentations and provide feedback to students was adopted from the University of Uppsala in Sweden, where a similar annual post-graduate symposium had been started by professor Staffan Ulfstrand in the 1980s. Ilkka Hanski, Esa Ranta, and others at the Department of Zoology in Helsinki were familiar with the successful symposium in Uppsala and wanted to introduce it to Helsinki.

The Tvärminne seminar was closely followed by the sudden death of Olli Järvinen (the 29th of November 1990 at the age of 40), Professor of Zoology at the University of Helsinki. After this sad event, a yearly seminar was started and was first held in April 1991 under the name “April Symposium”. This was the occasion when the prize for the best presentation was officially named “Olli’s prize” by Ilkka Hanski, who was an acting Professor of Zoology at the time, as a tribute to Olli’s memory.

Officially named in 1992, the Spring Symposium tradition has been kept up since a high-profile seminar for PhD students to present their work, with external evaluators giving valuable feedback both on the scientific content and presentational skills of the speaker. The sum for the Olli’s prize was initially 5000 Finnish marks (roughly 840 euros), and from the very beginning, it has been targeted to cover travel and accommodation expenses for attending an international congress. Today the 1000 euro grant is provided by LUOVA graduate school (Finnish School in Wildlife Biology, Conservation and Management).

The man behind Olli’s prize

Professor Olli Juhani Järvinen (1950-1990) was born in Jyväskylä, Finland, 3rd of October in 1950. He obtained his MSc degree from the University of Helsinki in 1973, after which he worked on ornithological projects in Sweden, Poland, and France. In 1980 he returned to Helsinki where he defended his PhD thesis on the “Ecological zoogeography of Northern European bird communities”. Olli acted as Professor of Zoology at the University of Helsinki from 1981-1990. As an enthusiastic bird watcher, his greatest scientific contributions came from ornithology and, in particular, the community structure of birds. Within his short-cut career, Olli published over a hundred scientific articles, mainly on ecology, zoogeography, and population genetics, in addition to hundreds of non-scientific articles, reviews, books, and booklets. He was a passionate speaker for wildlife conservation and believed in nature protection based upon sound biological research. Olli strongly disapproved of using vague phrases such as “the delicate balance of nature” and the assumed “truths” in the field that had, in reality, never been tested. With numerous publications and talks aimed at both the public and scientists, he brought hard facts and data to the ongoing discussion of wildlife protection in Finland. A vast majority of Finnish biologists today also know Olli as one of the authors of the book Sammuuko suuri suku? / Sista paret ut? (“Last pair out?”) – a deep and critical introduction to nature protection published in 1987, and a mandatory reading to all applicants of the university entrance examination in Biology in the 1990s.

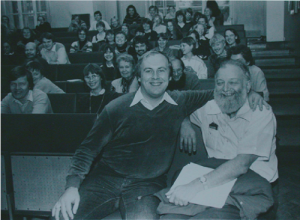

Olli Järvinen and Richard Levins (right) in Helsinki Zoological Museum lecture hall, 1982

Olli was a diplomatic negotiator, and as a board member of the Finnish Cultural Foundation, he greatly improved the facilities and working climate for young scientists. Through his connections, Olli arranged visits of acknowledged researchers from foreign institutions, which brought new life to advanced-level seminars at the department, bringing new life to advanced-level seminars. Olli’s commitment to teaching began during his studies in the Genetics Department, where he played a large role in developing courses. As a professor, he was appreciated for his ability to combine a broad knowledge of theory and solid experience of fieldwork. A good example of his broad-minded approach was a new field course, in which students would learn the latest methods of population genetics while addressing ecological questions. Olli’s attitude towards students was very encouraging, and he also established the so-called “Mickey mouse” seminar, where PhD students could present their research plans to get feedback about their ideas.

Counted in years, Olli’s life was tragically cut short but counted in deed and influence, it was exceptionally long and bright. In 1991, during the first official Spring Symposium (named April Symposium back then), the prize of the best presentation was named Olli’s prize to honor Olli’s lifework and the legacy he left behind.

The information of this page is provided by several sources: Ilkka Teräs and Ilkka Hanski personal communications; Kari Vepsäläinen, Academia Scientiarum Fennica Year Book 1991-1992 Obituaries, Olli Järvinen; Spring Symposium & Olli’s Prize (Poster) compiled by Emma Vitikainen from material provided by Kari Vepsäläinen, Ilkka Teräs, Ilpo Hanski and Hannu Pietiäinen.

Day-to-day life of PhD students and the atmosphere at the starting era of the Spring Symposium

A perspective from Lotta Sundström

The history of the Spring Symposium is quite well documented – how it was initiated and the history behind Olli’s Prize. Less is perhaps known about the day-to-day life of PhD students, and the atmosphere at the department at the time when the Spring Symposium was initiated. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, only some 15-20 post-graduate students were working towards their PhD degree within the department of zoology as it was then called. Also, rather few post-doctoral researchers were around, and the number of staff members was also much smaller. At the time post-graduate studies formed an unstructured process where supervision was almost non-existent – the notable exceptions being those supervised by Olli Järvinen and some of the younger staff members – and nobody really even dreamt of PhD courses. Olli Järvinen was instrumental in creating an open and supportive atmosphere, where students were encouraged to get engaged in dialogue with each other and create their own discussion circles. A proper curriculum for post-graduate studies was thus only beginning to form. This was the time when Ilkka Hanski and Esa Ranta were just past their post-doctoral period and were looking for more permanent positions in the department. During the 1990’s they, and Yrjö Haila, were to shape the future of the department together with the PhD-students at the time. I personally remember this time as the period when, owing to the absence of PhD- courses, post-graduate students created and held their own courses and so gained the necessary study credits and funding for their degree. As a side effect, we also gained very broad insights into ecological and evolutionary theory. It was indeed a very different world in which pressures for time constraints, public outreach, career development, and job prospects were much less prominent than today. I certainly did not give much thought to these matters.

The start of the Spring Symposium (or the April Symposium as it was then called) heralded an entirely new era in doctoral training at the department – it formed the first structured form of post-graduate training organized by the department. Although the number of PhD students was only a fraction of that today, almost twenty student presentations were given already in the first years. In addition, staff members also gave presentations. But the atmosphere was the same: excitement while preparing presentations, over what the invited experts would think about the projects, how the presentation would be received, and – above all – what questions would be posed. The symposium was held in the large lecture hall at the zoological museum where the department also was located. The lecture hall was usually jam-packed with staff and students alike. This difference in attendance between the early times and today sadly demonstrates the extent to which the workload of both staff and students has changed during the past twenty years. But it also reflects the fact that those in the lead in the early 1990s have moved on and new people will have to shoulder the responsibility. This has been done admirably by the PhD students who now run the entire organization.

Some aspects of the Spring Symposium have changed over time, as is appropriate. Most of these represent improvements – most notably the quality of the presentations. The change from hand-scribbled barely legible overhead sheets to visually very appealing PowerPoint slides, and from nervous mumbling from notes to confidently and professionally delivered presentations is remarkable. What I miss is the informal gathering of guests, staff, and students in the local pub after each day, where lively discussions continued until early morning. More than once one or more of the guests had to be more or less carried home afterward. The move to Viikki and the loss of the local pub with a cozy atmosphere has changed this tradition to a more formal dinner, but the element of dialogue between students and leading scientists is still there. The final evening party is perhaps all an older staff member can cope with so keep up this tradition.

Shifts in the topics and taxa of Spring Symposium talks

A review by Ilkka Hanski (1953 – 2016)

Twenty years is a long enough time for research topics to change substantially. In our field, community ecology was especially topical in the 1970s and behavioral ecology in the 1980s, while in the past decade many ecologists have started to employ molecular biology tools in their research. The presentations that have been made in the Spring Symposia (SS) over the past 20 years provide interesting material to examine how ecology and evolutionary biology have changed in Helsinki. Or have they?

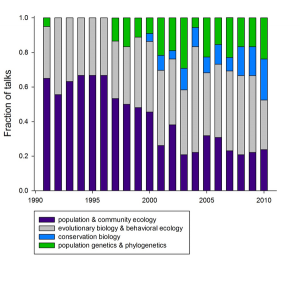

Figure 1 shows a rough classification of SS presentations into four categories. Population and community ecology appears to have experienced a steady decline from around 60% of the presentations in the early 1990s to just over 20% in recent years. Evolutionary biology combined with behavoural ecology have retained their share at around 40% over the years. I clumped evolutionary biology with behavioural ecology because many presentations could have been classified into one or the other. Population genetic and phylogenetic talks started to appear in the late 1990s and they now account for about 20% of all the talks, while talks that I considered to represent conservation biology are most recent, starting to appear in the past 10 years. One should not read too much into the details in Figure 1, because my classification is crude. Nonetheless, but what is very clear is the increasing diversity of research approaches and topics over the years. In addition to what is shown in Figure 1, we have had smaller numbers of presentations in taxonomy, morphology, developmental biology, physiology and theory. The numbers of these talks have slightly increased overtime, further adding to the diversity of topics.

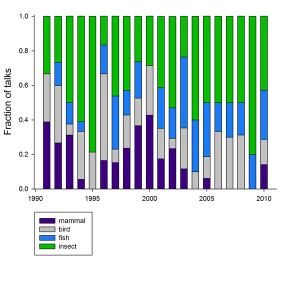

It is of interest to examine which taxa have been studied in empirical projects (Figure 2). Our department has had a great tradition in small mammal studies, which were still doing well in the 1990s, but the numbers of talks concerned with mammals have declined to almost nothing in the past years. The numbers of projects on fishes and birds have not changed much, while studies on insects have somewhat increased, and nowadays about half of the SS talks are on insects. A few talks on other invertebrates, plants and fungi add to the diversity.

The classifications that I have produced do not touch some of the most interesting and important issues, such as which kinds of statistical analyses have been applied in empirical studies, and how closely the empirical projects are related to relevant concepts and theories, and which kinds of concepts and theories. Unfortunately, it would be difficult if not impossible to analyze such questions with the SS abstracts. However, without any analyses I can testify, having been around for the past 20 years, that huge progress has been made on these fronts, as well as in the general quality of presentations. I expect that further integration of ecological and molecular studies as well as of empirical and theoretical studies will take place in the coming years and be reflected in SS presentations. The current diversity of approaches and topics is a distinct strength of ecology and evolutionary biology in Helsinki.

Spring symposium presenters: Trends and outlooks

A review by Liselotte Sundström

So with 20 years of data what can a scientist do but grind it through an analysis (or at least make graphs in excel)? Several patterns emerge and reveal changes in both the composition of presenters and the type of science done.

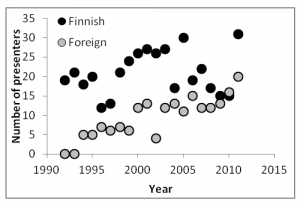

First, there has been a steady increase in the number of contributions. Second, although still lower than the number of native Finns among the presenters, the number of non-native presenters has steadily increased (Figure 3). This clearly reflects the extensive international exchange that all the units involved have experienced. Finally,

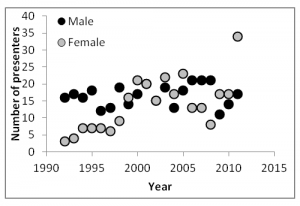

there has also been a clear improvement to the gender balance among the presenters (Figure 4). Indeed, the gender balance has been pretty even during the past 10-15 years, but 2012 stands out as the first time there are many more females than male presenters. Maybe we should start worrying? Be this as it may, science is alive and well.

The years have seen changes in the content and approaches. Applied ecology is advancing strongly, and this means there will be scientists properly trained in ecological theory to provide expertise to policy-makers. Nonetheless, also the basic science is advancing in giant leaps, with new approaches allowing entirely new questions to be addressed. This means we are not stagnating, but rather staying at the forefront of our chosen field of science.