(One of the great challenges of the Humanities is to increase the awareness of these different disciplines in today’s increasingly economics- & technology-based world: to show why the different studies in Faculties of Arts are elemental to the well-being of society, to the development of civilization, and to the survival of humankind. The following text is based on my deliberation on this, mostly in two presentations earlier this term, from the point of view of my own vocation in language and literature in general, and in English studies in particular.)

English is a world language, a lingua franca of the Internet, of popular culture, and of much of international politics. In the western world, English is often an expected and presumed second-language skill whatever the native language(s) of a country. In a number of contexts, English has reached the status of the the designated language of communication (e.g. in civil aviation). These are choices of safety, practicality, and circumstance.

In a world with this language set-up then, what is the role of academic English studies?

All language study is study of communication, of people’s minds and of their emotions. In the English-speaking world today, we need to study and understand phenomena like Brexit, Backstop, and “fake news”, and, on an even larger scale, we need to work through challenges like nationalism, prejudice, and environmental issues. This is why we study language.

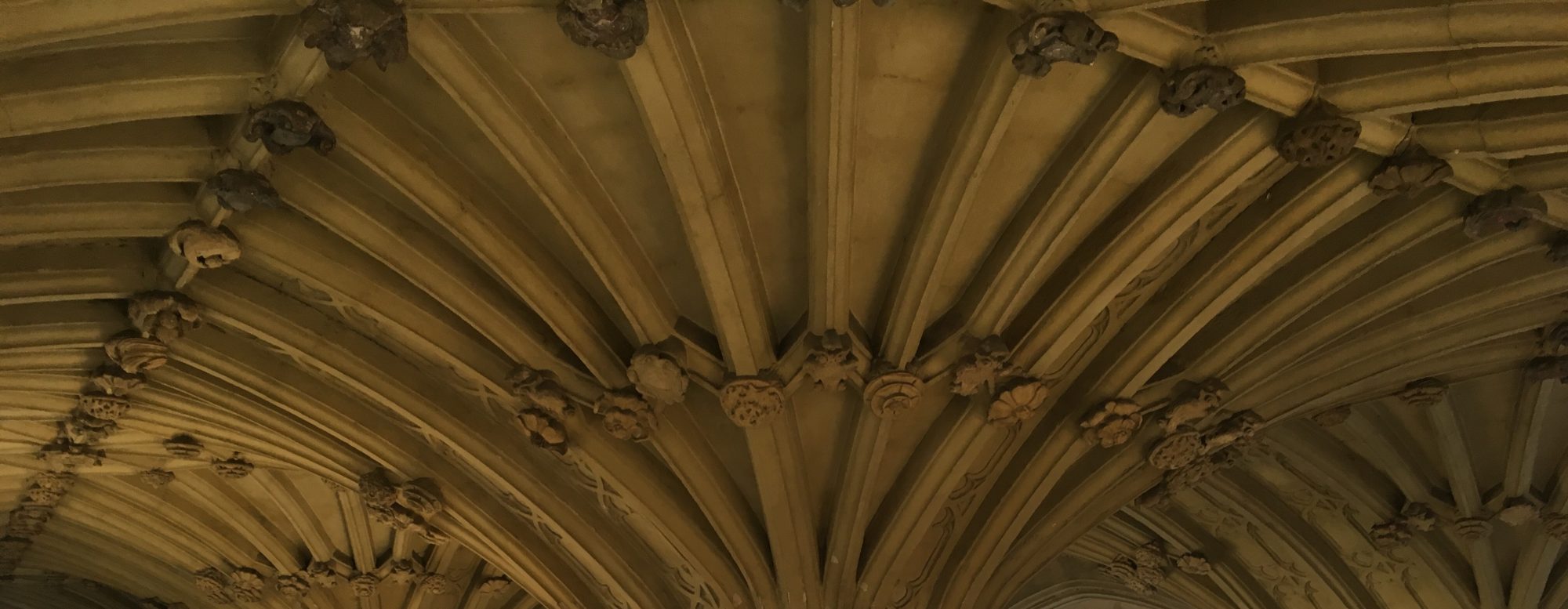

Furthermore, the academic study of languages is more than the study of contemporary language. In the case of English, it is the study of a language in the continuum of centuries of Judeo-Christian western tradition. In order to understand the language of today, we need to study the language of the past, and the literature created in that language, by the writers who saw the world change, and sometimes made that change happen. “Study our manuscripts, those Myriades / Of letters, which have past twixt thee and mee, / Thence write our Annals, [—]” prompts the poet John Donne (1572–1631) in one of his poems.*

Taking John Donne as an example, then: He lived in the London of Renaissance Humanism, harbouring the legacy of his great-uncle and the friend of Erasmus, Sir Thomas More (1478–1535); he suffered, and later embraced, the aftermath of the English Reformation; and he saw the Elizabethan era come to an end and the Tudor rule turn into the reign of the Stuarts that eventually open the way to the creation of the United Kingdom.

John Donne was also involved and interested in the exploration of and travel in the new world(s): he partook in naval campaigns with men like the Earl of Essex (1565–1601) and Sir Walter Raleigh (1552–1618); he was highly intrigued by the expedition of the Virginia Company; and he had a great personal engagement with the work of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). All these expansions of the known world — and of the mind of man — are reflected in Donne’s language and writings.

In the English-speaking world of today, we need to study writers like John Donne — as well as other writers of other eras — in order to find out how the world we know was formed and why. By understanding how the people were thinking and why they made their choices, we can make sense of where and who we are in England and in Europe today. Other scholars do the same in other languages and for other cultures. Together, eventually, we can hopefully make the future a better place.

* “Valediction on the booke” (ed. John T. Shawcross, 1967)