When settling into the form that we now most closely associate with the quintessential Victorian novel, the aim of prose writing was to inform, delight, and move its audience (in the true vein of the docere, delectare and movere of classical rhetoric). After its by-ways via imaginative travel-narratives and Gothic ghost-tales, the novel had found its form of realistic description as well as historical, social, and moral, close-reading. This development gives us classics like Charles Dickens (1812–70), William Thackeray (1811–63), George Eliot (1819–80), and the Brontë sisters.

In their various narratives, all these authors sooner or later include Christmas scenes in their stories. True to the mission to educate and affect, the descriptions of the seasonal festivities are no strangers to the realities of the times in which they occur, and often the joy and expectations of Christmastide are purposefully contrasted with the less favourable circumstances of the life of lower or middle class Victorians. Like when “the merry Christmas bringing the happy New Year” reminds Lydgate all too well about the expectations of debts to be paid in George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871–72; chapter LXIV); or the efforts to acquire new clothes and food for little Georgy for Christmas in William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847–48; chapter XLVI). Or when Cathy, in Emily Brontë’s (1818–48) novel, is arriving home to Wuthering Heights for Christmas, in an attire of “a grand plaid silk frock” (Wuthering Heights, 1847; chapter VII), strongly in contrast with her domestic environment; and when it is clear that Mr Pumblechook’s gift of a bottle of sherry and another of port to Mrs Joe (in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, 1860–61) is a generous gift at the humble home (chapter IV). Sometimes Christmas becomes a metaphor: For Charlotte Brontë’s (1816–55) protagonist a moment of loneliness and desolation is referred to as a “Christmas frost” and a “December storm” (Jane Eyre, 1847; chapter XXVI). And, of course, the Christmas-theme is epitomised in Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol” (1843), where a complete scenery of the goodness and evil of man is being portrayed before the reader in a fairy-tale-cum-ghost-story. In all these narratives, even the moments of joy include a reminder of the realities of every-day life.

The Victorian poet Christina Rossetti (1830-94), too, seems to illustrate her pilgrimage to the manger in a setting of her own contemporary landscape. In the “bleak midwinter” where, “frosty wind made moan, / earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone”, she is asking: “What can I give him, poor as I am?”. This poem also survives as a well-known Christmas carol. Indeed, another Victorian legacy that we encounter each holiday season is the service of Nine Lessons and Carols. This service from the late 19th century, celebrating the birth of Christ and anchoring it to the Old Testament prophesies, survives in a variety of Christian denominations today.

The music and lyrics intertwined with the biblical texts of the carol service represent a mixture of tunes and texts from the medieval times onwards (and later even especially commissioned post-19th-century works and arrangements). At the same time, however, the service also gives us a special insight into the Victorian era. Like Dickens, Thackeray, Eliot and the Brontës, the texts of the carols, while telling the story of the nativity, also refer to the life of the Victorians. The “little town of Betlehem” with its “dark streets” could much more naturally be a scene in 19th-century London. Also, “the poor, and mean, and lowly” we encounter in “royal David’s city” may just as well have wandered the streets of London in the 1800s. For the Victorians, in devotional music as well as in literature, the celebration of Christmas is closely related to their own social circumstances.

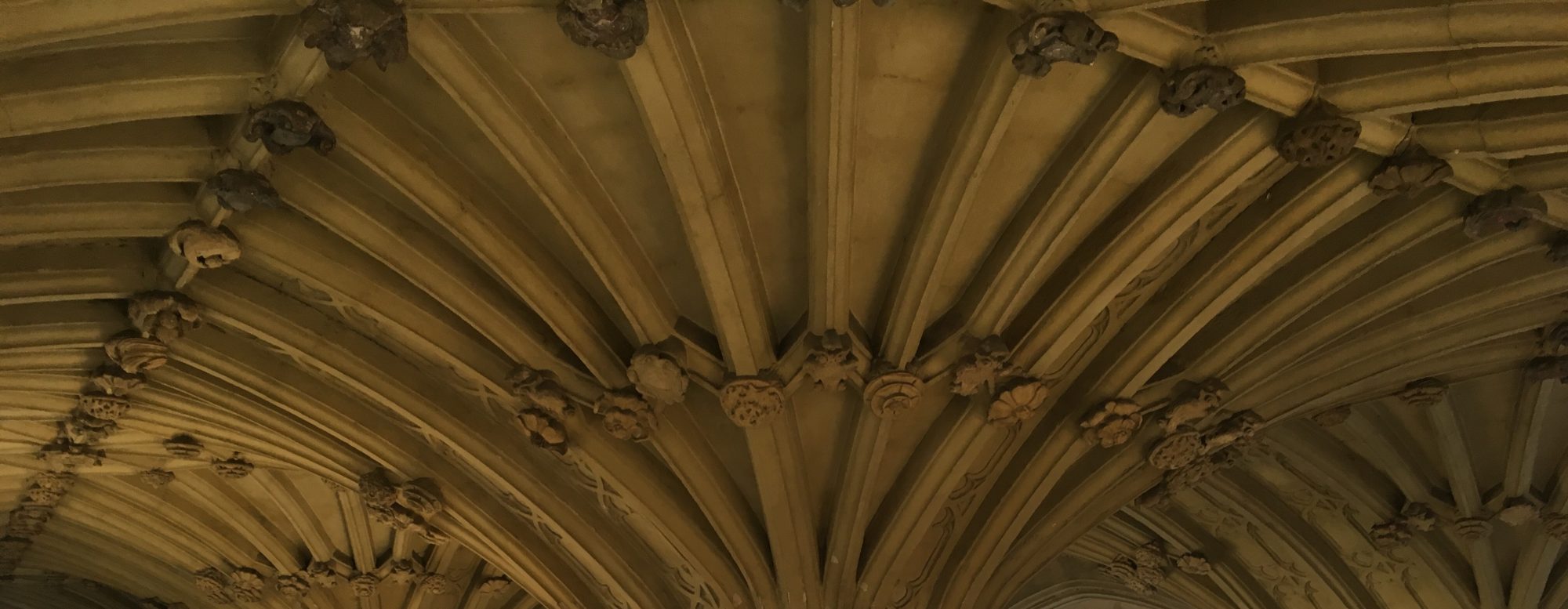

Although originating in a stable more than two thousand years ago in Betlehem, Christmas has always been a festivity anchored in the here-and-now. In a carol service earlier this month (appropriately, as a memento of Victorian London, in the very church where Charles Dickens’s parents were married in 1809), the texts and sermon speak of Christmas today: they include John Betjeman’s (1906–84) poem contrasting Christmas shopping in London with the “most tremendous tale of all”, as well as poignant references to the on-going refugee crisis in the Middle-East and the especially topical discussion on the escalated situation in and about Jerusalem. These Christmas narratives of today all suggest that Christmas, like in times past, must be made happen every year all over again. In the words of the preacher of this service: “It is in this real world, not in a fantasy world, that Christmas is celebrated.” Like in Victorian London, or on the fictional pages of a great novel, Christmas challenges us, every year, all over again, to share “a thousand thoughts, and hopes, and joys, and cares” (Charles Dickens, “A Christmas Carol”).

St Mary le Strand, London, venue of the Christmas Carol Service on 8th December 2017, address by the Revd Lucy Winkett.