by Sini Salko

Author: Katja Anniina

Contribution of tourism development to climate change and livelihood of local people in Greenland

by Kalle Nordling, Joel Owona, Martina Ravn, Frederik Siegstad and Joula Siponen

Tourism and air transport are among the sectors that contribute to climate change through construction of new infrastructure and direct emission from the aircraft engines. Aviation accounts for around 2% of world’s GHG emissions, however much of the current analysis and policies continued to ignore the sectors. Arctic countries such as Greenland and Iceland depend heavily on air transport. Available data from Visit Greenland show that tourists comprised a total of 64 % of all passengers flying in and out of the Greenland in 2016. This could be compared to Iceland ten years a go.

New technologies could help in reduction of aviation emissions; however, this needs to be developed. Our group investigated how increased tourism and aviation emissions contribute to climate change and the livelihood of local people in Greenland compared to Iceland. A number of local people from Nuuk were interviewed and our findings indicate that there is high potential of tourism development in Greenland. We also discovered that there is an exponential growth in tourism in Iceland since 2010 after volcanic eruption. These growth comes with some challenges which include infrastructural expansion, cultural issues and ecological sites destruction.

Greenland is therefore encouraged to collaborate with Iceland to learn from their experiences.

See animation in the link below to learn what we experienced during our visit in Nuuk and Iceland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDR2l3FwjGI&feature=youtu.be

Reference

Aviation emissions rates in Iceland – Google Search. (n.d.). Retrieved July 11, 2018, from https://www.google.is/search?ei=cAFFW_TxF9LxkwXOm7iIBw&q=aviation+emissions+rates+in+iceland&oq=aviation+emissions+rates+in+iceland&gs_l=psy-ab.3…7677.10438.0.13649.10.10.0.0.0.0.118.1059.2j8.10.0….0…1c.1.64.psy-ab..0.0.0….0.P2tvnCMtUZY

International Civil Aviation Organisation (2016). The World of Air Transport). (n.d.). Retrieved July 11, 2018, from https://www.icao.int/annual-report-2016/Pages/the-world-of-air-transport-in-2016.aspx

NIR Iceland 2017 submission May resub.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ust.is/library/Skrar/Einstaklingar/Loftgaedi/NIR%20Iceland%202017%20submission_May%20resub.pdf

Sharp, H., Grundius, J., & Heinonen, J. (2016). Carbon Footprint of Inbound Tourism to Iceland: A Consumption-Based Life-Cycle Assessment including Direct and Indirect Emissions. Sustainability, 8(11), 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8111147

Tourism Report Arctic Circle 2016.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.tourismstat.gl/resources/reports/en/r9/Tourism%20Report%20Arctic%20Circle%202016.pdf

How Greenlanders feel about the changing sea ice?

by Kangasaho Vilma, Lehmusjärvi Tuuli, Leppäkoski Janne, López i Losada Raül, Markussen Ullunguaq

-“I was born with ice around. If there was none, something would be wrong or not in balance”

As a part of our project, in Greenland we interviewed local people about their relationship with sea ice.

We wanted to interview people who have direct connection with sea ice, like getting their income and livelihood from it. Because of the time and locality constraints, we could not reach any people directly living off sea ice. Finding them at random is quite an unlikely event. The amount of traditional hunters and fishermen in Greenland has gone down rapidly. In 2013 there were less than 1800 people living on traditional livelihoods, and that was half of the number it was only 10 years earlier.

In total we interviewed 10 persons, of which 9 were males, and 1 female. The age distribution was from 20s to late 60s. The interviews were made in Nuuk and also in Kapisillit, a fishing village located in Uummannap Sullua fjord, about 100 km east from Nuuk.

We asked the interviewees their name, age, hometown (place of birth) and the following five questions

- Is there sea ice in your hometown?

- Has the sea ice changed in your experience?

- What does sea ice means to you / Activities?

- If there is no ice… how would that make you feel?

- Do you think Climate change is good or bad for Greenland?

We tried to make the questions as unbiased as possible, meaning that they would not lead the interviewee to any direction that might affect the answer. We probably succeeded in that, as we got quite diverse and formulated opinions from the people we interviewed.

There is practically no sea ice in Nuuk, so we tried to find people who would be from places with sea ice. In Kapisillit there is some sea ice in the area, though it was widely mentioned that extent has diminished from what it used to be, and the depth and quality of the ice has gotten worse. We found some people from areas of seasonal firm sea ice (eg. Tasiilaq in east Greenland).

-“Sea ice reminds you about who you are”

Sea ice plays noticeable role within Greenlandic culture and identity. Loss of sea ice can also mean that part of the people living in Greenland will lose part of their fundamental identity. The importance of the sea ice on the identity can also be seen from the fact that many of the interviewees said that they had never thought about not having sea ice in their lives. Also the aesthetic properties, such as sunlight glittering on the ice and the beauty of the winter sea ice were mentioned being important.

For the hunters knowing how to move on the sea ice is crucial. When they are children, they play on the ice and jump from one ice floe to another. Sometimes they fall into water, but this is a part of an important process to learn how to move on the ice and understand it’s behaviour. It is about being connected with the nature by direct experience, something that is not often practised in the western world.

There is also a spiritual dimension. The Mother of the Sea, Sedna, is the most famous of all Greenlandic legends, the goddess of the marine mammals. Sedna will punish the people by taking the animals away if they do not behave and show respect to nature. From this perspective, it was bit of a surprise to see that in Greenland there was rubbish thrown away into the nature.

So the sea ice has always represented possibilities and also food in the old Greenlandic history.

-“It means food, and possibility to get to the food. When there is ice, you can go places you really can’t go otherwise. Also you always can’t go those places using boat cause gas is very expensive and all the people don’t necessarily can afford it”

If the sea ice is lost, one more direct connection with the nature is lost. Of course for some, especially for people working with modern methods, the sea ice can be more of a hindrance. For example sea ice can make it harder to navigate with boats.

We also asked about the meaning of climate change for Greenland. Most of the interviewees we spoke with thought that climate change has two sides. It can be good for South Greenland as it gives more farming and fishing opportunities there. For more remote areas in North and East Greenland, where the culture is still more dependent on ice conditions, climate change has more likely negative effects. For example seals are more easily caught on sea ice than on open water.

In the end the sociology aspect of the course was an interesting experience to widen our perspective (as most of us were natural scientists) to have some first-hand experience of the viewpoint of the social sciences. It was also interesting how tedious it is to take notes while interviewing people, and the hardship of containing the real message in the interview notes.

-”There is no same kind of beautiness than with sea ice anywhere else in the world”

Integrating sea ice loss into decision making in the Arctic

by Kangasaho Vilma, Lehmusjärvi Tuuli, Leppäkoski Janne, López i Losada Raül, Markussen Ullunguaq

Sea ice can be found throughout the year in the Arctic, as a result of freezing of the upper water layer of the sea. Its extent varies from year to year and depends on the dominant weather conditions. The minimum of the sea ice appears in autumn and the maximum just before the sea ice starts to melt, usually during the spring. Apart from the natural yearly variation of the sea ice extent, climate change is also playing a major role, since the largest warming is happening in the Arctic according to different climate change scenarios and, therefore, the sea ice is retreating to more northern latitudes. On top of this, a potential link between human coastal activities and further sea ice loss has not been widely researched.

Sea ice is an inherent element within Greenlandic culture and the identity of its people. Traditional livelihoods in Greenland greatly depend on fishing and seal hunting, and the latter one is largely dependent on the sea ice – if there would not be sea ice or the sea ice would be too thin, seal hunting would be greatly hindered. In year 2013, there were less than 1800 people living on traditional livelihoods and the amount is decreasing rapidly. Sea ice is also an important component in Greenlandic mythology, and it provides a leisure element. After all, sea ice is not only important from a climatic perspective but also from a cultural one.

Fracturing sea ice floating near Ilulissat, North Greenland.

Climate change is a pressing issue that can vastly affect the sea ice extension. Sea ice is regarded as an important aspect of nature to the Greenlandic society, which immediately leads to the necessity of protecting the sea ice.

This project focuses on the hypothesis that local human activity can enhance sea ice loss/thinning at least at a local scale.

Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies the impacts that human activities pose on humans and the environment. This is done in such a way that the impact of individual products or services can be assessed, and so, this methodology can be used as a helping tool to make educated choices on different alternatives.

LCA provides a framework to quantify impacts under different impact categories, which in the end aims at holistically assessing the impacts of products and services. This framework does not yet consider sea ice loss that is not directly derived from climate change, but from human actions.

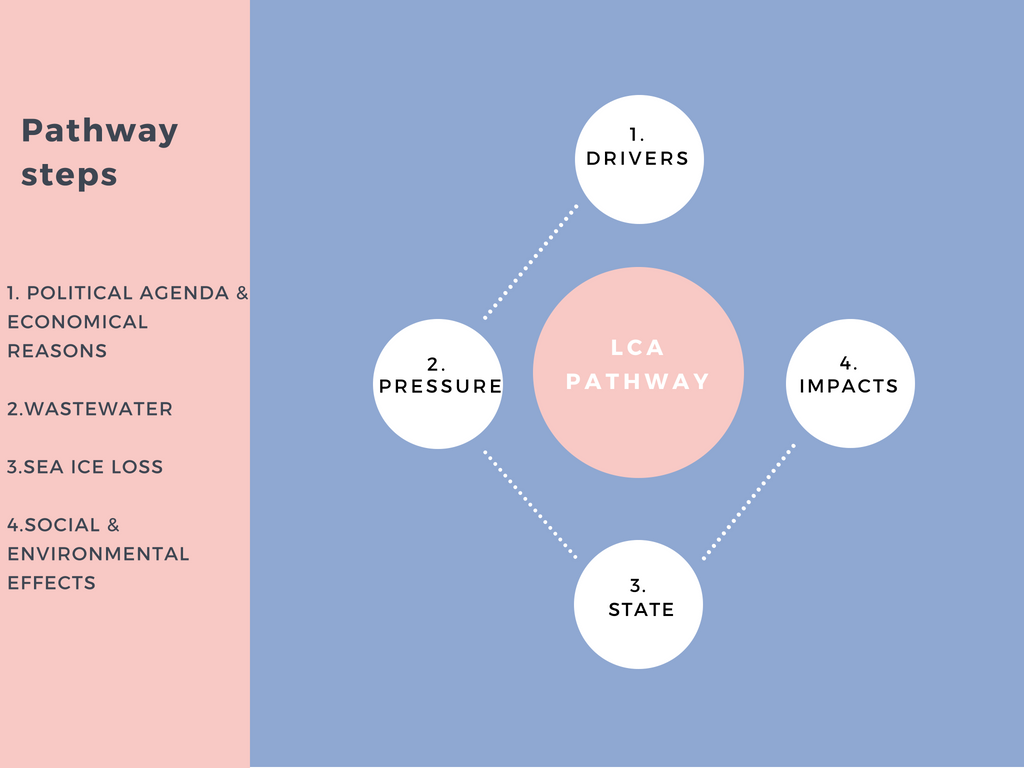

The goal of this project is to initiate a debate from which sea ice loss could arise as a new impact category to be covered on LCA cases from the Arctic region. In order to do so, the EU recommended DPSIR (Drivers-Pressure-State-Impact-Responses) approach is used. Roughly summarised, major economic or societal drivers exert pressures to the system which change their state in such a way that produces an impact. As a result of this impact, responses may appear altering any of the previously given components, thus modifying its outcome in an iterative process.

Under this approach, an LCA impact pathway is built by defining its four first elements (Drivers-Pressure-State-Impact), so that an outcome from a certain human activity can be translated into impacts to humans and the environment. Responses are left aside from this analysis as they greatly depend on political factors that are not meant to be included under LCA methodology, which is in the end a tool designed to assist decision making.

On the left hand side, the panel describes steps for the Arctic sea ice loss. LCA pathway steps are represented on the right hand side.

- DRIVERS

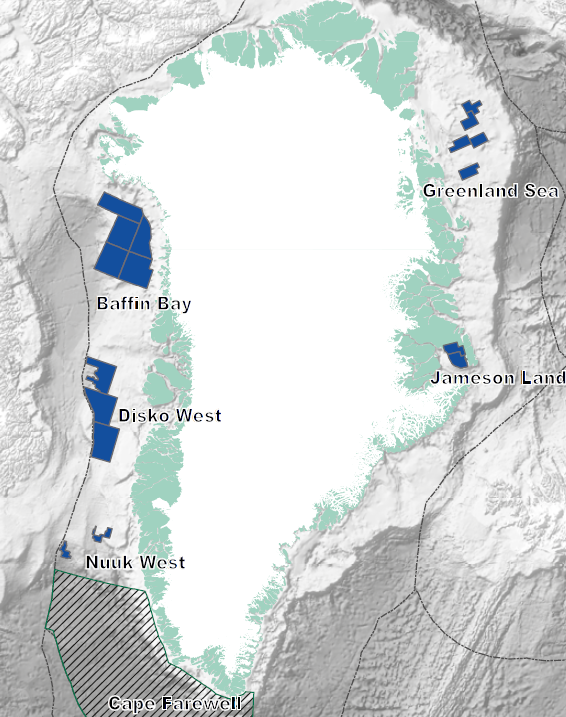

Human activity in Greenland is mainly located in coastal areas, mostly focalised within its numerous fjord systems. There are several economical, political and societal factors that are expected to drive an increase of the human activity through coastal Greenland:

- It is on the Greenlandic political agenda to aim for a self-sustaining economy that does not depend on the yearly grant from the Danish government. In order to achieve that, Greenland has directed its attention towards its vast reservoirs of mineral resources. Within these prospective scenarios, numerous mines would be established through the Greenlandic coast, thus increasing substantially human influence in these areas.

- Tourism has not yet been developed extensively in Greenland. However, there are reasons to believe it will increase significantly over the following years.

- Population increase due to warming climate favouring farming conditions in southern Greenland

- PRESSURES

All of the above points will to a greater or lesser extent contribute to an increase of human activity in Greenlandic coastal areas. An immediate effect that can be derived from such a prediction is an increased production of wastewater.

Wastewater streams in Greenland are directed into the sea, with none or close to none treatment. This is due to the very sparse distribution of population, which makes it very difficult to build treatment plants that are worth the effort – and this without mentioning the difficulties of wastewater treatment at -50 ºC.

Apart from chemical pollution or nutrient excess, wastewater streams being poured into the sea can account for thermal pollution due to temperature differences between both water systems. This effect, depending on the temperature and the streamflow of wastewater, could potentially lead to local loss or thinning of the sea ice layer.

- STATES

As a result of the pressure from incoming heat from wastewater into the sea, the sea ice could melt completely, or decrease in its quality (i.e. thinning to a dangerous extent where it is not possible to stand on it anymore), mostly at a local level in the area surrounding the effluent. This effect would be combined with an already existing warming Arctic due to climate change, and thus possibly magnify its consequences, especially in those limiting areas where the sea ice has been retreating the most over the past years.

- IMPACTS

The relevance that the sea ice has within Greenlandic culture was already emphasised to provide a rationale based on which it is desirable to consider it as an element in nature that should be protected. However, this fact does not comprehend the whole nature that its loss might signify, and so impacts are further categorised as social or environmental:

- The impact that the sea ice loss can cause from a social perspective has been studied by fieldwork consisting of interviews with Greenlanders encountered in Nuuk and Kapisillit. The results of these interviews show that, even if there is not so many people relying on sea ice anymore for their subsistence (as the hunting population is small and diminishing), sea ice is regarded as a valuable aspect that should not be lost, as it is part of the cultural identity of Greenland. In fact, some of the interviewees were astonished at the possibility that their hometowns would not have sea ice anymore (more about the interviews and cultural side of sea ice in the separate blog post).

- There are also several studies that focus on the environmental impacts that sea ice loss can cause. A reduction of the albedo would cause a boost on climate change. Sea mammals, which are dependent on sea ice to rest and to grow their cubs would retreat along with it, and polar bears would have a difficult time finding food. On top of it, several species of phytoplankton and algae rely on sea ice for their growth. Overall, enhanced climate change and diversity loss due to a retreat of arctic marine and ice ecosystems would represent most of the environmental impact of sea ice loss.

CONCLUSION

Sea ice in Greenland is an element of nature that is receding mostly due to climate change and its warming effect in the Arctic. Increased coastal human activity could further boost this effect.

A proposal to update LCA methodology with a new impact category covering sea ice loss due to human activity has been studied. This update could be important in order to provide comprehensive information to decision-makers in relation to projects that would increase substantially coastal human activity, such as mining sites.

The impact of the sea ice loss has been tracked following the DPSIR approach. On this basis, several economic, political and societal drivers have been found that could lead to an increased coastal human activity in Greenland, from which increased wastewater streams could lead to heat pollution in the sea leading to sea ice loss.

Sea ice loss impacts have been studied from a social perspective by means of interviews, to ponder how valuable sea ice is regarded by local communities. Environmental effects of sea ice loss at an ecosystem level have also been explored.

Further work is required in order to incorporate this newly described pathway into LCA methodology, such as the definition of quantifiable magnitudes of emissions and their effects on sea ice, which could go on the direction of quantifying heat content in wastewater discharge.

The work produced under this project could easily be extrapolated to other arctic communities where sea ice is present and so plays an important role on its livelihoods and ecosystems.

Fisherman in Kapisillit, Greenland.

Greenlandic society: is fishing the future?

By Joonatan Ala-Könni

Our bus takes a turn from the center of Nuuk, and starts heading to the harbor. A truck sporting a smiling shrimp on its side accelerates on the pier, behind the inconspicuous white-and-blue building, the sort that are plentiful in this city. This building has a small emblem signifying the purpose of this house: the office of the Greenlandic hunters and fishers association, “KNAPK”.

Our group had prepared a set of questions that we thought could reveal how the climate change is currently pushing fishermen to adapt in the front of the rapidly changing Arctic.

We climb stairs up to a balcony running around the second floor, ask a man smoking outside whether he is our guy, Bjarne. He says no, waves us to walk inside, and while I’m nervously struggling with the door the smoking guy says something to me. I turn back and notice he’s pointing at my bus ticket on the balcony, I apparently managed to drop that from my hat. Confused about why there was bus ticket in my hat and whether I should say “sorry” or “thanks”, I step into a very plain office, with a hole in the roof and a coat rack that was able to take my jacket only after a careful balancing act.

We are greeted by two guys, Bjarne and Kaka, who have set up a coffee pan and cookies on the table for us. Everything here speaks of actually working, and not trying to create an impression of working for some high-ranking visitors. Genuine, I think. After some initial anxiousness I’m starting to feel good about this interview.

We sit around the table chitchatting but soon turn to asking our prepared questions. Very quickly it turns out that adaptation is pressed by fishing quotas, price of fish and labor shortage. I’m actually quite surprised by this, I was expecting changes in sea ice patterns and unpredictable weather to be the thing we are talking about, not economical issues.

So, this report is not about climate change, but a change in the attitude of people towards the historical, and current, mainstay of Greenlandic economy: fishing. Bjarne underlines in no uncertain terms, that the number one problem the Greenlandic fishing industry is facing currently is finding suitable workers for the factories and ships. Greenlandic economy is protectionist, and they can do this since they had their own “Grexit” way before it became fashionable, back in 1985. Factories and fishing companies operating in Greenland need to have at least 2/3 ownership in Greenland, and local workforce can be favored over foreign. Unemployment in Greenland has been hovering at around 10%, but every year over a thousand workers come from abroad, mainly from Asia and Eastern Europe, to work in the new factories.

So what is causing this peculiar situation? When this question got brought up during the interview, Kaka says that the young people are interested only in playing video games, and not working. Bjarne nods in acceptance. I mumble something about this sounding familiar, but I get a feeling that the reasons must be a little deeper than that. Let’s start looking at possible explanations.

First thing that comes to my mind is that the work might be low paid, but this is not case. The fishing industry in general has been doing great in Greenland: the prices of fish have been rising since 2008 and the fish stocks are in good shape. The work is seasonal in general, but the pay can be very high, over 100 000 DKK (approx. 14 000 €) per month on the large off-shore factory ships, where workers spend sometimes weeks at a time. The season might be really short, only a few weeks for some species, but the hours can be ruthless. 6 hours of work, 6 hours rest, and repeat until the season is over. This might discourage some from the work on larger ships, no matter how well it is paid. The factories pay by the hour, with a typical hourly wage starting from 15 €, with extra paid for weekends and holidays. For someone without education, this is a decent deal still, and the work is more regular than the work on the factory ships.

One reason could be a lack of choices, which may feel very uninspiring in a world where individual freedom is something that is valued very high. “If you are an uneducated, unskilled Greenlander, especially young man you don’t have many choices. Then you have to become hunter, fisherman.” says Bjarne. But then again, many of my friends are struggling with the blinding variety of choices presented to them, and feel paralyzed by it all. So choosing the path of your future is stressful anyways.

Could the work be dull and soul crushing? When I ask Bjarne and Kaka about how pleased fishers and hunters are in general about their jobs, I get an answer: “They are very pleased, even with low income. They are like lonesome rangers, they like the independence.” Of course, this probably does not account for the factory workers, but at least fishing and hunting are usually satisfying occupations. And with the new licenses for fishing prioritized for young Greenlanders, a career as a “dinghy-fisher” is definitely attainable.

Although both of us interviewing the officials afterwards had the feeling that the conversation had been very sincere, I thought something was missing from the picture. While talking with a local adolescent, one likely explanation was brought up, and it regards situations in Greenlandic homes. Domestic violence is very prevalent and the rate of sexual abuse among children and youth are among the highest in the world. This quite obviously leads to mental health issues, which combined with alcohol and drugs, leads to a serious impairment in the abilities of many people. Escaping reality with video games and intoxicants can seem like a very desirable solution for many young people. These issues are obvious for the people living in it, and the society is taking measures to tackle them.

Currently, the Greenlandic economy is completely reliable on fishing, which accounts for about 90% of the export. Although, as the “For the Benefit of Greenland” report outlines, this model of economy is very fragile, this is the reality that people have to work with. With a brand new trawler fleet, processing plants on ground and improved boats for fishing in fjords, the catch is posed to increase still. But if labor force is not to be found from Greenland, new workers are needed from outside. This is problematic with a small, mostly indigenous population, that is already feeling that their cultural heritage has been eroded by foreign control.

In order to fix problems in the economy, something needs to be done to break the spiral of domestic violence and abuse. And it starts with the minds of the young, so that they don’t just move their emotional load to their own children.

Fishing in the Arctic & Climate Change

by Michael Platou, Luciana Capuano Mascarenhas, Marja Hemmilä, Joonatan Ala-Könni, Sini Salko and Sebastian Abel

The Arctic is warming at a faster rate than the rest of the world, and it is expected that this will bring both benefits and challenges. An Arctic with warmer temperatures has less sea ice, which hinders local traditional transportation and ice hunting. At the same time, warmer oceans lead to fish species travelling northwards seeking for cooler waters and shipping routes become more available with less sea ice. Hence, the overall expectation is that climate change will increase fishing opportunities in the Arctic.

The focus of our group project was the interface between fishing in Greenland and Iceland and climate change. We wanted to check if the promised fishing opportunities will not bring any challenges or unintended consequences that might not be considered in the mainstream discourse about the future of the Arctic. To understand how future changes in the climate might affect the industry, we wanted to understand the past challenges that were faced and what has been done in terms of adaptation to those changes. We were also interested in knowing how big is our stakeholders’ concern with climate change and how it affects decision-making.

During our 12-day trip to Greenland and Iceland, we conducted interviews with local actors that were relevant to our subject:

- Bjarne Lyberth and Tønnes “Kaka” Berthelsen, from KNAPK (The Organization of Fishermen and Hunters in Greenland);

- Ilannguaq Abrahamsen, factory manager from Royal Greenland A/S;

- A local fisherman from Kapisillit, Western Greenland;

- Karl Egede, local fishermen associated with Polar Seafood Greenland A/S;

- AnnDorte Burmeister, scientist at the Department of Fish and Shellfish, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources;

- Dr. Ólafur S. Ástþórsson, from the Marine & Freshwater Research Institute in Iceland;

- Dr. Kristján Þórarinsson, Population Ecologist advisor for the Icelandic fishing industry.

With the interviews, we gained a good perspective about how the industries work in both countries, as we talked to different types of stakeholders, from fishermen to businessmen, from consultants to researchers. A lot of the inputs we received were consistent with what other actors have said, increasing the credibility of the information given.

We found that the growth in the fishing industry that we read about is already happening. In Greenland, new pelagic fish species are being fished (such as mackerel), fish catches, licenses and prices have increased over the last years. However, a major concern regarding the expansion of the sector is the amount of labor needed. Greenland has a small population of less than 60,000 people and, reportedly, as the Greenlandic society becomes more modernized, younger generations are gradually losing interest in becoming fishermen. KNAPK stated that Greenland will probably have to do as Iceland and rely on migrant laborers from other countries. This can bring unintended consequences, like cultural and social shifts. Reflections and insights regarding our interview with KNAPK can be read in our post Greenlandic society: is fishing the future?.

While we conducted our work, we noticed that Greenland and Iceland have similarities regarding the fishing industry. Iceland has gone through a fast development of the country, mainly driven by a growing fishing industry and, in recent years, to tourism. The country also reverted an overfishing situation before a huge collapse happened in the 1970s (the cod crisis affected many countries in the North Atlantic back then). Iceland is seen as a successful case by some Greenlandic actors, serving as a role model. According to Icelandic researchers, Greenland is facing the same trade-offs and challenges Iceland faced 40 years ago. We discuss this subject in more depth in our specific post What can Greenland learn from the Icelandic case?.

When we brought up climate change in the interviews, none of the actors showed to be very concerned about it. There is a general optimism about the growth of the industry that has been happening. You can understand how we experienced this in our post The optimistic fishermen in Greenland. No specific plans are being done to tackle upcoming challenges, it has been stated that when things change, they will adapt, as done before. The adaptation in the fishing industry is usually shifting target species. KNAPK also represents hunters, and those are being more affected by shrinking of sea ice. In Kapisillit, seal hunting and ice fishing is becoming more and more rare; on the other hand, boat fishing is becoming possible in winter time. This speaks directly to the ability of Arctic people to adapt to the climate: each year is different to the other and there is a common understanding that nature is uncontrollable. We give a more overview on our post Climate change and adaptation in Arctic fisheries.

Lastly, one of our hypothesis was that the expansion of the fishing industry would probably mean conflicts or pressure on small-scale fishermen. What we found in Greenland was that smaller vessels fished in coastal areas, which included the fjords. Larger vessels (including big trawlers) were mostly fishing off-shore. The two largest companies, Royal Greenland and Polar Seafood, have associated with local fishermen, in addition to their own. The companies set the prices and buy the fish from local fishermen. They offer financial assistance (loans), so fishermen can improve their boats and fishing gear, as long as fishermen sell only to that company. We could not fully assess the advantages and disadvantages of this system, but the fishermen we spoke to seemed quite satisfied with it.

Michael, Luciana, Marja, Joonatan, Sini and Sebastian

Adaptation to climate change in Arctic fisheries

Text by Sebastian Abel

The Arctic regions provide for some of the most productive fishing grounds in the world. Nutrient-rich water and the presence of species with a high market value have the potential to generate large profits for fisheries. However, Arctic ecosystems are highly susceptible to changes in the environment, that directly affect the size and distribution of fish stocks. In the most severe cases, this can cause a species of fish to disappear to a large extent from a region. An example for this is the collapse of Cod stocks in Greenlandic coastal waters in the 1960’s. This meant that the economically most important fish species at the time was no profitable to harvest. Fisheries have to adapt to these changes in order to remain profitable.

The cod is one of the most important species for Arctic fisheries.

Photo: Joachim S. Müller, Flickr

In the interviews we conducted with people involved in Arctic fisheries, it became clear flexibility is one of the most important measures necessary to be able to quickly respond to changes in available fish stocks. When Cod became unavailable, local fishermen quickly adapted by shifting to Halibut and shrimp as target species. According to the Greenlandic fishermen we interviewed, the Cod stocks have recovered in the recent years. This allowed fishermen to concentrate their efforts on this species, making it once again their most important catch. Due to the current instability of Cod stocks, Halibut and shrimp still remain vital catches to support economic stability. Other species, such as Redfish, Lumpfish and Salmon seemed to make up only minor shares of the total catches, especially in Greenland. Investments from larger fishing companies have allowed for the modernization of fishing gear that help to steadily increase catches, also in less productive years. While this can provide fishermen with the means to buffer harder times, care should be taken that this does not lead to overfishing in the long run.

Fishing harbor in Kapisillit, Greenland. Photo: Joula Siponen

Changes in fish stocks, such as the collapse of Cod stocks in the past have been primarily driven by water temperatures. So it comes at no surprise that climate change, with the expected rapid warming of the Arctic, will cause further shifts in available species for fisheries. The exact changes are hard to predict, but the arrival of new species to the Arctic – for example the mackerel in Greenland – has the potential to create new opportunities for local fishermen. In addition, existing stocks of Cod could further thrive in the warming water. In accordance with these predicted changes, the fishermen we interviewed shared an optimistic view to their economic situation in the future. This creates a rather unique situation for people in the Arctic; while many populations around the globe are worried about the adverse effects of climate change that they will be exposed to, the people in the Arctic could have a chance to benefit.

Nevertheless, specific measures to prepare for a changing environment are hard to make. Fisheries in the Arctic are relying on their adaptive capabilities they exhibited in the past to be applicable in the future. Our interviews indicated a focus on immediate, reactive measures in favor of the development of long-term “emergency plans”. This adaptive strategy could be beneficial, as it retains a high amount of flexibility when facing unpredicted changes. Optimizing the fleet ahead of time for newly arriving fish species, on the other hand could bear the risk of investing into a change that might not happen.

What can Greenland learn from the Icelandic case?

Text by Michael El-Madani Platou, social science student, University of Greenland

Fisheries are the largest national income in Greenland, besides the annual grants received from the state of Denmark, which was implemented under the Homerule Act from 1979. The fisheries have stood for 90 percent of the total exports in the last 20 years, and roughly consist of 50 percent of the country’s GDP today. The fisheries in Greenland have since the 80’s been developed to be more efficient and economically viable, with a quota system controlled by the Greenlandic government, which divides the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) amongst the approved fishing companies and smaller actors in the fishing industry. In a perfect world where the TAC limitations are followed, the different marine populations would be sustainably preserved, so the fishing industry does not fluctuate and thereby affect the vulnerable main income in the near future. In that way the fishing is sustainable and the next generations of Greenlanders can enjoy the benefits of the fisheries.

That is unfortunately not the reality of the situation today, as most statistics have shown in the recent years. Overfishing occurs almost consistently, due to the country’s development reliance on the income. This can result in a decline in catch after some time, and even completely remove the natural resource, which has happened in the late 1800’s with whaling, and almost happened with seal hunting along Greenland’s westcoast in the early 1900’s.

Today the community of Greenland argues about the lack of communication between the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (GNR) and Naalakkersuisut. GNR which in accordance with North Atlantic Fisheries Organisation and the International Council for Exploration of the Sea, provide the data and recommendation the government requires to create the quotas. The government complains about the quality of the recommendations from the Institute. On the other hand, the scientists of the fisheries in Greenland complain about the lack of compliance from the government to follow the recommendations provided by the Institute. This has created a situation where the government discredits the scientist through the media and the public adopts a one-sided opinion, which in turn supports the decision regarding quota setting, irrespective of the recommendations.

This exact situation can be compared to the Icelandic cod situation in the late 1900’s. About 40 years ago, Iceland’s economy faced a rather difficult situation, as the income originating from fisheries was about 85 percent of the GDP, which meant they highly relied on the fishing industry in their economic development. The fishing eventually lead to overfishing, which would endanger the society without any other income basis, so the scientists lead a campaign to make the government and the people aware of the approaching dangers. This caused a backlash on the scientists’ credibility in the society. The politicians behaved like the quotas were set as an auction by the highest bidders, and the society believed that the more you fish, the better. Eventually, the scientists struggle payed off, when the government introduced a new 25 percent rule (catch rule = 0.25 * exploitable biomass) which would result in an economic decrease, but in turn also provide a more sustainable fishing industry. However, this gave an incentive to develop other economic areas such as industrial-/ tourism industries. In regards to the social crisis, the reduced fishing resulted in the government investing in small high-tech vessels, which gave the population a more stable and efficient self-sufficiency. In 2011, the fishing industry consisted of 27.1% of Iceland’s GDP.

The moral of the story is that the Greenlandic government’s fishing industry must begin its struggle in the development of a sustainable fishing policy, which will preserve the biomass in the Greenlandic fishing waters, while also developing new income sources to replace the immediate loss in revenue. These other income sources have already been introduced to the Greenlandic people – tourism and industrial development – which are also comparable to Iceland. Another thing that has been a subject in the economic council in Nuuk February, 2018, was the need for a renewed measurement strategy for the estimation of TAC, so the over-/ under estimation is lessened in future recommendations, aiming for sustainable fishing. The Arctic has always relied on the marine natural resources for survival, and will probably continue to do so over the next century; Thus, it is very important to establish a sustainable fishing culture amongst the Nordic countries, in the midst of man-made climate changes. It is better to give the rights to fish to your next generations than to deny them their right to prosper.

The optimistic fishermen in Greenland

Text by Marja Hemmilä

(Photo by Laura Riuttanen)

For such a small city, Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, has many harbors. We walk through them, and try to find the one with the fishermen. Finally we arrive to the right harbor. We smell the salty sea air, fishes and seafood. We walk around and try to find somebody to interview, and finally we go into a blue building with the Royal Greenland sign. With the help of two friendly receptionists, we find our way to another building, and find Ilannguaq Abrahamsen, the factory manager of Royal Greenland Nuuk. Because it’sf late in the afternoon, he is heading home, but kindly makes some time for our interview. The 34-years old father of two, has come to Nuuk on December 2017 and got the job. He is very enthusiastic about the future; Royal Greenland is expanding and going to have more fisheries around Greenland. To answer the question, if there is any plan B in the case that, for example, cod would disappear like it did in the 1960s, he answers that “we have to see, what season gives us and we have to feel the sea that we have”. Overall we get the feeling that he is very optimistic about the future and not afraid of, for example, the changes that a warming climate will bring.

On Thursday noon, we embark and start our trip to Kapisillit, a small village more inside of the same fjord as Nuuk. We can feel the wind in our faces and see the oldest bedrocks in the world. Near Kapisillit, the captain drives us around an iceberg, and we all are in total ecstasy, the view enchants us. When we arrive to Kapisillit, we get to interview a local fisherman about his job. There is lots of cod nowadays, and that makes him happy. He also serves us some Greenlandic snacks like whale skin and seal blubber. We taste them, but the feeling in the mouth is a bit too strange for most of us.

On our last day in Nuuk, later in the same week, we go back to the harbor aiming to interview the factory manager of Polar Raajat (Polar Seafood). Unfortunately (and totally understandable) he has already left work at Friday afternoon 16 o’clock, but luckily we find a fisherman, Karl Egede, who is willing to speak with us. He has fished all his life, and now he is associated with Polar Seafood. He is very pleased with the situation, hence through this association, he gets better equipment and catches more fish. He also seems to be opportunist to the future. When we ask, if he had noticed anything in fishing about climate change, he tells us with a laugh, that this year is colder than year before.

Overall the fishermen that we interviewed seemed to be very optimistic that they and other Greenlanders could adapt the changes that climate warming will bring. The fish stocks are assumed to grow via new species in the area, so also in that point of view the future for the fishermen seems full of light.

Making money or preserving nature? – The Greenlanders’ opinion about oil industry

by Arto Heitto, Liine Heikkinen, Nina Sarnela, Otso Peräkylä, Yuqin Liu and Heikki Junninen

Currently fishing is the primary livelihood of Greenland. In order to achieve stronger economy Greenland is investigating the potential of new sources of income: oil drilling is one of the most prominent ones. Oil industry in the pristine Arctic environment easily provokes negative thoughts among people looking at it from a distance. But what are the feelings of people that would really be affected by it? This is what we wanted to find out when we made our way to Greenland’s national oil company, Nunaoil, for discussion and also conducted a small survey on the streets of Nuuk to find out opinions of citizens towards oil industry.

Treasure hunting in the Arctic sea

Nunaoil is a small company with five staff members. It participates in all oil exploration and exploitation licences in Greenland. This Greenland’s government-owned company has been working for over thirty years now but in addition to some test drillings, no oil has yet been drilled in Greenland nor has any decision about starting to do that been made. We went to meet Nunaoil’s legal advisor, Betina Præstiin, and senior geologist, Signe Ulfelt Hede, to discuss Greenland’s prospects in oil industry and got warmly welcomed to the office of Nunaoil in the centre of Nuuk. In the interview their love of Greenland and strong need to strengthen its economy came across.

Betina and Signe see the oil exploration as a treasure hunt – large discovery of oil could really make a difference for Greenland. Oil industry was seen as a mean to achieve the needed economic growth and the possible risks that could come along with it were thought to be under control due to the liability contracts under which all the oil companies are working. Betina and Signe introduced us to the thought that Greenlanders don’t want their land to be just a national park where tourists can visit and send a postcard from, but instead they want it to be more independent, well functioning state. The discussion gave us a lot of new information but left us wondering what is the public opinion in Greenland towards the oil industry.

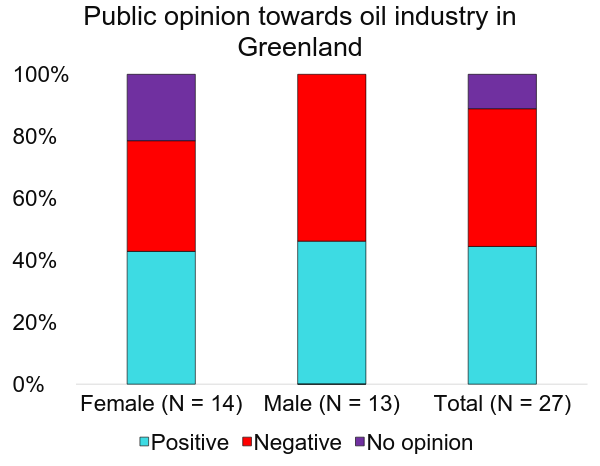

Finding the public opinion in Nuuk

So to get some insight about the public opinion, we then scattered to the streets of Nuuk to make a quick survey about the people’s attitudes towards the oil industry in Greenland. We asked a total of 28 people how they felt about starting oil industry in Greenland and got 27 answers, both for and against the idea. Unfortunately, due to our shortage in language skills, we were mainly restricted to interviewees that spoke English, but still we felt that we got quite good overview of public opinions. We were a bit surprised to find out that the majority of the people we met didn’t have any strong opinions about the issue. This is actually quite understandable since even though the explorations have been done for years, no decision about starting the oil industry has been done, so the topic is not on top of people’s minds.

Getting a new perspective

When doing the survey we heard several thoughts and concerns of the citizens. The economic situation of Greenland was on people’s mind and many of the interviewees were in favour of oil industry because it’s possible contribution to economic growth. The concerns that rose in many discussions were the possible changes in society due to immigrants coming to work in Greenland and the environmental risks. Since the fishing industry is currently the main livelihood in Greenland, the possible conflicts with it were also worrying some of the citizens. In total the opinions were divided very equally between positive and negative feelings towards oil industry. We had a fun day discussing with many friendly Greenlanders and we learned totally new perspectives to the prospects of oil industry in Greenland from them. We can recommend this kind of exercise to all natural scientists – just go out and listen to the opinions and ideas of the public. We promise it will widen your perspective of things!