(Blog adapted from Socialist Visions of American Dreams: The Finnish Settler Lives of Oskari Tokoi and Frank Aaltonen by Rani-Henrik Andersson & Rainer Smedman in Finnish Settler Colonialism in North America: Rethinking Finnish Experiences in Transnational Spaces Rani-Henrik Andersson, Janne Lahti (eds.)

In the summer of 1921, two Finnish immigrants met on the streets of Sault Ste Marie, Canada.

There was a short discussion in a very straightforward, even Finnish, way:

– Aren’t you Oskar Tokoi?

– But who are you?”

– I am Frank Aaltonen from Hollola Lahti, but I live close by on Sugar Island and I came to take you there. “

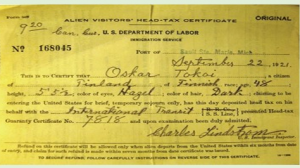

Oskari Tokoi agreed to Frank Aaltonen’s request and ended up in a rowing boat crossing the Canadian-US border to Sugar Island on the US side. The crossing of the border was questionable, since Oskari Tokoi did not have the necessary permits to enter the United States. Thus, he became an illegal immigrant.

Oskari Tokoi and the “Vanishing Race”

Oskari Tokoi immigrated twice to North America. Between those journeys he became the first Prime Minister of Finland. Born in the village of Kannus, Finland in 1873, Tokoi left for North America as a 17-year-old boy in 1891. He traveled first by ship across the Atlantic to New York, from where the journey continued on a week-long train ride across the U.S. to the coal mines of Carbon, Wyoming.

Oskari Tokoi’s arrival in the American West coincided with a time when the resistance of the indigenous peoples of the region had just been crushed. Tokoi was certainly familiar with the fate of the local Indian tribes since it was only a few years since they had been removed from the Black Hills area. Lakota reservations were not far from Lead and Natives were present both in the Black Hills and in the cities in the area. In 1892 Tokoi had his first encounter with a group of Lakota, along the Platte River:

“One day in late autumn, the government announced that a passing Native American tribe would visit the locality. The announcement called for the saloons to close the windows so that the Indians would not even be able to look inside. In the evening, when the men were just coming out of the mine, a huge crowd of Indians were riding along the road. The riders were all young, healthy men and women. It was the famous Sioux [Lakota] tribe that, with their herds of horses, moved south for the winter. There were about five hundred riders, all in the original Indian costumes with their feathered headdresses. They were followed by more than hundred wagonloads of older people, mostly women and children. There were a total of two thousand of them.”

Tokoi went on to describe the Sioux as the “last Indian tribe still living wild on the entire American continent,” raising the idea of them being still wild and as such a potential danger in their primitive state. None of them, except for an old woman, could speak English and as evening came they pitched up their tents and many Finns who had never seen so many Indians began to fear. “What if these wild beasts in their natural state, for some reason, became enraged, then they would sweep such a society away from the face of the earth with a single swipe!” pondered Tokoi, but in a tone of relief, he concluded that “they did not go wild. In the morning, they assembled their tents and stuff in the usual order and continued their journey to the south calmly. What could be their goal? At least the Finns did not know it.

Tokoi did not mention that the lands he was staying on belonged to the natives, nor did he comment on their removal. To him the Indians passing by were not the rightful owners of the land, rather relics of the past, the last wild Indians that civilization had left to become the vanishing race. Years later he elaborated on the vanishing race paradigm writing:

“White conquerors tried to force the Indians into slavery and obey their laws and manners, but it did not come to anything. And even now Indians, the original inhabitants of America, are under much wardship and more oppressed than any other race. But they have not given up and not a single Indian has been enslaved but they have rather died than succumbed. And as a result of this oppressive politics, it looked like the number of Indians constantly decreased whereas all other races, including the blacks that were brought as slaves, increased and it looked like the entire race was doomed to die.”

Tokoi embraced the American idea of free land, the American dream, and the privilege of a white man to which the Natives did not belong.

A Colonizer, Farmer, Racist?

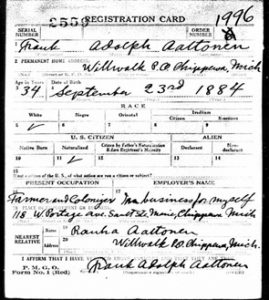

Frank Aaltonen, born in Hämeenlinna in 1886, arrived in the United States in 1905 and initially lived in Western Michigan, where he began organizing the Negaunee Labor Organization already the year of his arrival. Unlike Tokoi, he did not come into contact with the native people in the area, before his move to the Sault St. Marie Area and Sugar Island. Instead, he threw himself wholeheartedly into the affairs of the working-class people, in the socialist cause.

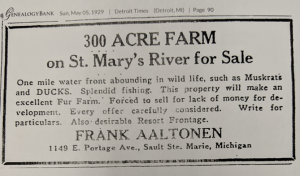

Frank Aaltonen traveled widely in the United States and Canada, but never in his correspondence or newspaper articles does he touch upon the native people of the country. Not before he sets his eyes on Sugar Island, Michigan, does Aaltonen take the time to address the Indigenous people, the Anishinaabeg of the area. Aaltonen saw the land on Sugar Island as free. It was there for the Finn, the superior woodsman and farmer, to colonize. The blood that ran in their veins was that of “true pioneers”.

The indigenous people may have owned parts of the land, but Aaltonen, fully believing in the Finn as a superior race and the native as the vanishing race, suggested that Finnish presence on the land would bring civilization to wilderness. The full blood Anishinaabeg whom he clearly believed to be racially superior race to the mixed bloods, fully supported his civilizing efforts, whereas the mixed bloods opposed him. Aaltonen ranked the native people based on their blood quantum, physical appearance, but also by their willingness to help him “improve” the island. To get the natives’ support, he promised them employment and with that, a part in the (Finnish) American dream. Aaltonen even declared himself a colonizer.

Oskari Tokoi too traveled around the United States and Canada, taking one job after another. One might assume that witnessing the poverty most Indians were forced to live in would have in some way influenced both Tokoi and Aaltonen, both of whom came from relatively poor conditions and were interested in socialism. However, this is not evident in their writings. During his travels in Nevada, Oskari Tokoi met a native man sitting by a lone fire with a bottle of alcohol between his legs. The man gestured to Tokoi to join him. Tokoi described the meeting.

“I was hesitant to approach the man. The Indian himself did not seem hostile or scary; rather he had a friendly appearance. However, the almost empty bottle made me weary. I had heard that booze makes an Indian fierce and they can get so fierce that their original savage instincts take over and in that stage the savage mind stalking for white man’s scalp may take possession and cause destruction.”

Tokoi continued to describe this encounter:

“To demonstrate his approval the Indian then wanted to show me all of his tribe’s war songs. An old canister abandoned by the fire could act as a drum and I had to sit there with a stick in my hand to beat the drum with this monotonous rhythm that is characteristic to all Indian dances. And the redskin danced. At certain intervals, he stopped to take a sip from the bottle. After that the dance got fiercer and wilder. Instead of a tomahawk, he held big pieces of burnt wood in his hand throwing them occasionally in the fire with tremendous anger, causing the embers rise high in the air. The dance would have been funny and interesting to anyone unless the looming danger of the Indian forgetting being civilized, and suddenly believing that he was doing a real war dance that required a reward in the form of a white man’s scalp. Due to the whiskey and exhaustion, the Indian’s knees started to wobble and after a couple of high-pitched screams he laid down and fell asleep.”

Romanticism, Paternalism and Settler Colonialism

In their memoirs Tokoi and Aaltonen return to Native Americans, even though they are not at the center of focus, rather a curiosity of a distant past. For both, Native Americans were the people whom the Finns met – and got along with – at the Delaware colony in the 17th century and continued to maintain a friendly relationship because of their similarities in character. Tokoi went as far in his romanticized idealism that he wrote: “I have no intention to claim, or prove, that the Indians and Finns are of the same race, although I absolutely have nothing against it if a scientist would prove such a thing.” Perhaps they were not of the same race, but both were an honest people, who liked to stick to themselves and lead a simple life in the woods, he believed. For Tokoi, this special bond between the Native and the Finn was still alive in the mid-20th century: “The similarity, should I say kinship, of Indians and Finns, was convincing also in this Second World War. Finns demonstrated their excellence in northern wilderness fights, where they, as children of nature, could take advantage of all the benefits of nature and thus win the strongest of opponents”. Similarly, Native Americans “proved their excellence in wilderness and jungle battles. As children of nature, they have developed their sight and hearing to incredible levels and they have the ability to adapt to nature and use all the benefits of the environment,” wrote Tokoi to a friend, continuing with what today could be viewed not only stereotypical, but highly racist description: “The Indians were even more skillful than the Japanese and were able to hide themselves and unexpectedly like leopards attacked the enemy. And the Indians had so much better instincts than the whites that the number of fallen and injured among the Indians was remarkably lower than among the whites.”

Frank Aaltonen too expressed highly racist views of Native American, categorizing them through their blood quantum and depending on how willing they were to support his colonizing plans. Later in life both Tokoi and Aaltonen, however, reflect upon the native people in very romanticized fashion. However, even when they evoke positive images of the natives, it is often in connection with Finns. Tokoi pointed out that Finns always “treated Native Americans with respect and honesty and when The US government finally in the 21st century adopted a more similar approach, the civilization of the Indians, if it can be called such, has happened much faster. They go to school nowadays and take up all the common jobs, like doctors, lawyers, teachers etc. but still rarely become operators of machines or hard industrial labor. They love the nature the freedom of nature. They remain proud of their race and their racial qualities, which they want to retain and leave as inheritance to their children. And the love toward the nature, simple natural life. Finns have also tried to hold on to their freedom and the nature, and so have the Indians.”

In a very nostalgic, paternalistic and racial tone he ended his letter to a friend saying: “At least they (Native Americans) give this country the best any race can give: freedom, love, and honesty.”

The notion of settler-colonialism adds a new dimension to the actions and ways of thinking of Frank Aaltonen and Oskari Tokoi. Both men, as immigrants to the United States bought into the idea of the American Dream and neither saw taking native lands as improper, let alone wrong. It was all about civilization and racial hierarchies. Aaltonen proudly declared himself a colonist, who wanted to civilize the wilderness and the natives were there either to help his efforts or to die off as a vanishing race. Tokoi never mentioned colonization or taking Native lands, even though his early travels in the U.S took place just around the time when native resistance to colonialism was crushed, and most native tribes were forced on reservations. It is interesting that both men were eager to fight for the poor, the working class and believed in an agrarian society, but Native Americans had no place in that society. It was clear to both that the Finnish immigrant had the right to seek the American dream and that the free land – and its use for agriculture or mining, for example – was justified, regardless of what the indigenous peoples of the region thought. In the case of Tokoi, it could have been a matter of indifference, even innocence, but Aaltonen’s action aimed at the establishment of a colony on Native lands, demonstrating his ignorance. However, both men participated, either consciously or unconsciously, in activities that may well be considered typical settler colonialism. For them Native Americans were the vanishing race that by the mid-19th century had become what could be described as noble savages. In their later writings both men promoted the stereotype of Finns and Indians as people of kindred spirit, honest yet simple.

In any case, the common ground for the men’s friendship was found in their experiences in the new homeland and socialism, which made Tokoi and Aaltonen eventually work together on behalf of the old homeland. Their new homeland, however, signified opportunity, freedom and an ideology that both men wholeheartedly espoused. Both Tokoi and Aaltonen spoke and wrote sympathetically about Native Americans in their later years but those were late born sympathies colored by the nostalgia of a bygone era and misguided notion of a vanishing race, and even then it was always in connection with their vision of Finns as special immigrants and about a particular Finnish American dream.