Writer: Olli Saukko

In this post, I continue with evaluating the process of researching the background of Sugar Island Finns. As the first post presented the sources and challenges of this research, this post concentrates on some of the findings I made during the process.

The peaceful, harmonious and united Finnish community?

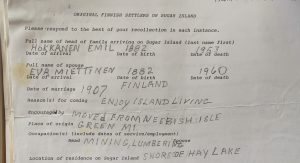

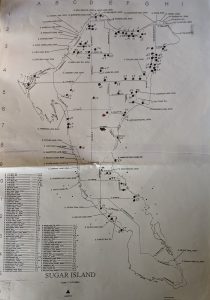

W  hen beginning to look for the background of Sugar Island Finns in Finland, there was a hunch that maybe they had some common history in Finland and perhaps some of them had lived in the same area before getting together on Sugar Island. The truth turned out to be quite the opposite. When looking at the aforementioned 25 Finnish families, there were nearly no common birthplaces at all. Their birth towns scatter almost all over the southern half of Finland: Lahti, Muhos, Seinäjoki, Virrat, Hämeenlinna, Honkilahti, Kuopio, Jämsä, Oulainen, Vaasa et cetera. The material of Allan Swanson’s research gave some hope concerning this, however, as the material showed that a couple of Finns – namely Emil Hiltunen, Esko and Elsa Kaikkonen, Ade Waisal [Abel Waisanen] and Lauri Karimo – hailed from the same town in Finland, Lapinlahti. But that was only a bunch of people and none of these mentioned were on the island in 1920 yet.

hen beginning to look for the background of Sugar Island Finns in Finland, there was a hunch that maybe they had some common history in Finland and perhaps some of them had lived in the same area before getting together on Sugar Island. The truth turned out to be quite the opposite. When looking at the aforementioned 25 Finnish families, there were nearly no common birthplaces at all. Their birth towns scatter almost all over the southern half of Finland: Lahti, Muhos, Seinäjoki, Virrat, Hämeenlinna, Honkilahti, Kuopio, Jämsä, Oulainen, Vaasa et cetera. The material of Allan Swanson’s research gave some hope concerning this, however, as the material showed that a couple of Finns – namely Emil Hiltunen, Esko and Elsa Kaikkonen, Ade Waisal [Abel Waisanen] and Lauri Karimo – hailed from the same town in Finland, Lapinlahti. But that was only a bunch of people and none of these mentioned were on the island in 1920 yet.

The material found in the collections of Ancestry is largely official by its nature, and it does not offer very deep or detailed information about the life stories of the people studied. There were some exceptions, however, a few of which were rather stunning as well.

One of these cases was the daughter of Oscar and Hulda Aho. I found out that the mother Hulda traveled with all her children from Canada to the United States in 1913, as Oscar was probably working in the country already. Among the children was Emmi, then 9 years old, who I could not find in the Aho family in the 1920 census. My first thought was that maybe Emmi had died as a child during those years. Then I scrolled the census list further and understood why Emmi was no longer among the children of the Aho family. It was because she had married their neighbor, Wäinö Soini, who was then, according to the 1920 census, 37 years old, to Emmi’s 16, and they also had a child William, who was born in 1919. With only these sources, it is of course not possible to say what kind of background this marriage had 100 years ago, but it is hard not to think that it might have not been how Emmi Aho hoped her life to be. Nevertheless, the 1930 census record of Sugar Island suggests that the significant age difference was somewhat embarrassing to them, as in this census their ages are marked as 29 years (Emmi) and 39 years (Wäinö). After 1930, the traces of the family disappear and I did not find how their or their children’s lives continued.

One of these cases was the daughter of Oscar and Hulda Aho. I found out that the mother Hulda traveled with all her children from Canada to the United States in 1913, as Oscar was probably working in the country already. Among the children was Emmi, then 9 years old, who I could not find in the Aho family in the 1920 census. My first thought was that maybe Emmi had died as a child during those years. Then I scrolled the census list further and understood why Emmi was no longer among the children of the Aho family. It was because she had married their neighbor, Wäinö Soini, who was then, according to the 1920 census, 37 years old, to Emmi’s 16, and they also had a child William, who was born in 1919. With only these sources, it is of course not possible to say what kind of background this marriage had 100 years ago, but it is hard not to think that it might have not been how Emmi Aho hoped her life to be. Nevertheless, the 1930 census record of Sugar Island suggests that the significant age difference was somewhat embarrassing to them, as in this census their ages are marked as 29 years (Emmi) and 39 years (Wäinö). After 1930, the traces of the family disappear and I did not find how their or their children’s lives continued.

In addition to the fate of Emmi Aho, there was another rather memorable series of findings, which was about a couple living on Sugar Island. In 1920 they lived in their own farm on the island. Then I noticed from the following census records that in 1930 they did not have their own farm anymore, but were instead living as boarders elsewhere in Michigan, which implies that during the 1920s they encountered difficulties in their life. Then I found a divorce record, a kind of document which I did not encounter very often during my searches. The wife had filed for divorce, and in the document the “cause for which divorced” stated: “Extreme cruelty”. The divorce was granted. The ex-husband continued his life in Michigan, and from the 1940 census records I found out that the wife had moved to the state of Washington. She lived with a new partner in a rural area and they both worked as “masseurs”, which seems like quite unusual profession. It seems that the wife found a new direction to her life after the cruelty she experienced in her marriage.

How far left is too far?

When looking at the Finnish people of Sugar Island as a whole, I found myself assuming that they were one united group among other groups on the island that came from different backgrounds. In the end, however, I found several hints that the Finns weren’t finally so united all the time, but instead had disagreements and clashes. As an example, Jarl Hiltunen, a Sugar Island Finn who gathered material for Allan Swanson’s study that was mentioned earlier, wrote in this material about the family of Frank Kuusisto: “They were so far left politically that we did not socialise with them.” On another occasion in the materials, Hiltunen cherished his memories of playing pinochle game as a child with Toivo Aaltonen (politically active Frank Aaltonen’s brother) and his wife Martha.

When looking at the Finnish people of Sugar Island as a whole, I found myself assuming that they were one united group among other groups on the island that came from different backgrounds. In the end, however, I found several hints that the Finns weren’t finally so united all the time, but instead had disagreements and clashes. As an example, Jarl Hiltunen, a Sugar Island Finn who gathered material for Allan Swanson’s study that was mentioned earlier, wrote in this material about the family of Frank Kuusisto: “They were so far left politically that we did not socialise with them.” On another occasion in the materials, Hiltunen cherished his memories of playing pinochle game as a child with Toivo Aaltonen (politically active Frank Aaltonen’s brother) and his wife Martha.

As an example to underline this difference, in the township board elections in 1928 and 1929, there were two lists of candidates, Progressive Ticket and People’s Ticket, and both of them had Finnish candidates. Frank Kuusisto – who was “so far left politically” – was on the People’s Ticket list and the influential Frank Aaltonen on the Progressive list. Furthermore, in a township board meeting in 1928, Frank Aaltonen stated that Emil Hytinen should not be allowed to vote as he was not truly a citizen of the United States, and along with that, Aaltonen accused Hytinen of escaping the World War I drafts by moving to Canada before the war and staying there for a few years before returning to the country. In the records it can be found that Hytinen understandably reacted quite angrily to these accusations and finally did not have a possibility to vote, and neither did his wife Emma.

Concerning Jarl Hiltunen’s remark on Kuusisto family, it should perhaps be mentioned that being politically left in general was probably not the problem, as many politically active American Finns were indeed on the left, but the differences had to do with “how left” they were. More information on the political activity of American Finnish people can be found e.g. in these two publications: Reino Kero’s “Suomalaisina Pohjois-Amerikassa” (Siirtolaisuusinstituutti: 1997) is a basic work about the different aspects of the life of Finnish immigrants in America. Gary Kaunonen’s “Challenge accepted: a Finnish immigrant response to industrial America in Michigan’s copper country” (Michigan University Press, 2010) concentrates especially in the state of Michigan.

Towards network analysis

When looking back to my year in this project, I think it was a wonderful opportunity to be part of it during the project’s first year, and it will be interesting to see what more information will be found of that curious group of Finns in the small island of Sugar Island. I find it inspiring that these kinds of findings of “traditional” historical research that I made will in this project be complemented with the data brought by new methods and viewpoints through the network analysis tools. I look forward to see how the HUMANA research project progresses later in 2020 and 2021!

Keywords: Sugar Island, Finnish American history, Finnish church records, Finnish American socialists