In a recent paper Dumas‑Mallet et al. (2020) have raised “concerns about the influence of the media on the research communication and dissemination.” In this text, I describe what might happen when a small group of academics decides to reward or “shame” journalists for their reporting on the same issues these academics cover in their research.

The recently established Active Travel Academy’s Media Awards at the University of Westminster “recognises excellent work by journalists and reporters covering issues around active transport and road safety” (Active Travel Academy’s website, 2020). This seems as a noble initiative because news coverage of active travel in UK is often negative: “Sustrans’ Xavier Brice presented his thoughts and mentioned some recent research by the charity that found 60% of news coverage of active travel was negative” (Aldred, 2020).

An expert panel of judges was supposed to select winners in seven categories such as news (written word), news (broadcast), student journalist, etc. Anyone including journalists could nominate their own or others’ work. In addition to these seven categories, there was a separate category “People’s choice award” for best and worse reporting on TV/radio/in print or online; however, it was unclear how the winners would be selected (Active Travel Academy’s website, 2019). Typically, people’s choice awards of any kind include massive (online) voting on a preselected list of choices. Open nominations are also possible if the number of potential voters is expected to considerably outnumber the potential winners. It is unclear to me what the organizers of the awards expected to happen regarding their people’s choice awards, and my repeated questions on Twitter were unanswered.

Regardless of the unclear selection procedure, I nominated a journalist for his, in my view, awful article (Reid, 2018) about bicycle helmets. The journalist interviewed only one researcher involved in a long-term scientific debate and allowed him to question the other party’s motives: “It’s notable that the university research group (which wrote the 2013 paper and others) seem very interested in rebutting [my underline] any suggestions that cycle helmets are not a panacea for safety.” This is an issue that is central to research integrity and it is unusual that researchers openly and publicly question each other. When that happens, an unbiased journalist should give a chance for the criticized party to respond. This journalist has not done that. In my nomination letter, I also list several other problematic issues in this journalist’s article (Radun, 2019).

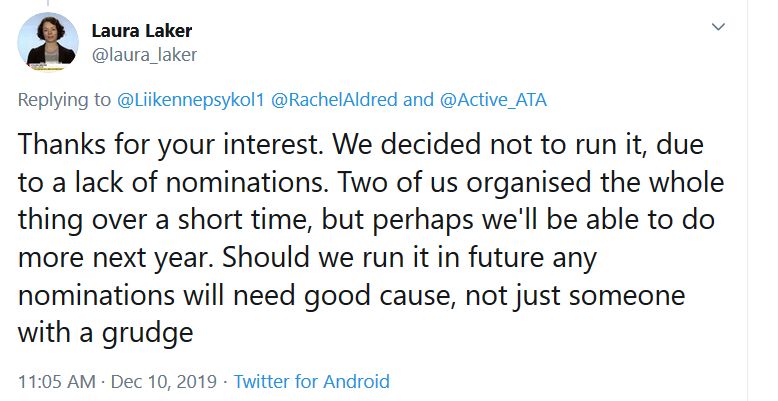

To my surprise, the “People’s choice awards” have not been awarded. After my repeated questions on Twitter, one of the organizers finally responded. She wrote: “Thanks for your interest. We decided not to run it, due to a lack of nominations. Two of us organised the whole thing over a short time, but perhaps we’ll be able to do more next year. Should we run it in future any nominations will need good cause, not just someone with a grudge” (Laker, 2019).

After this answer I started to wonder how many nominations were needed in order to declare it a “People’s choice”? More than two? Ten? Two hundred? If the organizers have overestimated the interest of people in their awards they should in my view have transparently reported this, not delete the “People’s choice awards” from their website and pretend they never existed. They should, I think, have also apologized to those like me who spent some hours writing their nomination letters and were left wondering what had happened. Despite my repeated questions, they have not done any of these things. What I received instead was a somewhat unsubtle impugning of nominator’s (or my?) motives: “Should we run it in future any nominations will need good cause, not just someone with a grudge.”

I don’t know how many nominations were received for the “People’s choice awards”. Perhaps they were unhappy that I nominated one of the most prominent pro-cycling journalists for the worse reporting award. It did, however, come to me as something of a surprise that this should happen with the eminent academics and journalists involved in the Active Travel Academy’s inaugural Media Awards. It is also led me to think about certain questions concerning who are the supposed “good guys” and who are the “bad guys”. Is one a good guy if one votes for the predetermined favourite, and is one a bad guy with a grudge if one dares to criticize these favourites?

The media have always been important for the dissemination of scientific knowledge. Their influence on the formation of the public opinion regarding whatever scientific issue is undisputed; however, the media can also play a significant role in the promotion of particular research fields, researchers and their institutions as Dumas‑Mallet et al. (2020) article suggests. In situations when these compete for research funding, an increased media visibility, at least a positive one, without any doubt improves their public image and perhaps places them in a better position in this fierce competition for funding. Therefore, researchers and institutions aware of the media’s power are interested in maintaining good relationship with them.

In conclusion, I cannot stop wondering whether establishing of the Active Travel Academy’s Media Awards was indeed a good idea. And to whose benefit it was established. Perhaps time will tell. Nevertheless, it is well known that a good cause does not always justify the means.