Olin mukana kahdessa tieliikenneonnettomuuksien asiantuntijatyöryhmässä (työikäiset ja iäkkäät) ja tässä lausunnossa haluan tarjota näkemykseni yleisesti tieliikenneonnettomuuksien ehkäisyn ja tutkimuksen tilaan. Kuten tämän lausunnon lopusta näkyy (Liite 1), olin Tieliikenneonnettomuudet-asiantuntijatyöryhmissä ainoa yliopistotutkija, jonka työ keskittyy täysin liikenneturvallisuuteen. Muut mukana olleet henkilöt, mukaan lukien muut yliopistotutkijat, olivat myös asiantuntijoita ja heidän panoksensa oli epäilyksettä ehdottoman tärkeä. Haluan tässä kuitenkin keskittyä vähenevään liikenneturvallisuuden asiantuntijuuteen Suomen yliopistoissa, koskien erityisesti liikennepsykologiaa. Nähdäkseni tällainen asiantuntijuus on välttämätöntä tieliikenneonnettomuuksien ehkäisemisohjelmissa sekä liikenneturvallisuuden parantamisessa.

Vielä vähän aikaa sitten Suomessa oli kaksi liikennepsykologian professuuria ja yksi liikennelääketieteen professuuri. Liikennepsykologian professoreiden eläköidyttyä professuurit ovat menneet muille painotuksille, mikä on johtanut heidän ryhmiensä hajoamiseen. Liikennelääketieteen professuurin kohtalo Helsingin yliopistossa on tällä hetkellä avoin Timo Tervon eläköidyttyä. Tämä tarkoittaa, että haasteena on liikenneturvallisuustutkimuksen jatkuvuus ja uusien tutkimusryhmien muodostaminen on erittäin vaikeaa. Koko rahoitus (palkat, yleiskustannukset ja tutkimuskulut) täytyy kattaa ulkopuolisella rahoituksella. Tämä aiheuttaa alalla haastetta erityisesti kahdesta syystä.

Ensimmäinen syy on, että tutkimusrahoitusta jakavat tieteelliset säätiöt käsittävät liikennepsykologisen ja liikenneturvallisuustutkimuksen usein liian soveltavaksi heidän rahoitettavakseen. Tieteellisillä säätiöillä ei yleensä ole kiinnostusta rahoittaa projekteja, jotka koskisivat esimerkiksi kevytautolainsäädännön vaikutuksia liikenneturvallisuuteen. Tämä valitettavasti tarkoittaa sitä, että yliopistotutkijat voivat harvoin suoraan osallistua liikenneturvallisuuden parantamiseen Suomessa, koska heidän tulee ohjata tutkimuskysymyksensä alueille, joita tieteelliset säätiöt rahoittavat. Lisäksi tällainen tieteellinen rahoitus ei kata osallistumista liikenneturvallisuustyöryhmiin, yleisten lausuntojen antamista tai osallistumista yleisten dokumenttien tekoon, kuten luonnokseen Koti- ja vapaa-ajan tapaturmien ehkäisyn tavoiteohjelmasta vuosille 2021–2030. Nämä vievät aikaa, mutta näihin projektityöntekijät (kuten minä) eivät saa rahoitusta. Aika on poissa projekteilta tai vapaa-ajasta.

Toinen syy on, että liikenneturvallisuusprojekteille jaettava rahoitus on selkeästi aiempaa keskitetympää. Traficom on päärahoittaja ja tyypillisesti tilaa projekteja, joiden arvioidaan olevan ministeriön/hallituksen linjausten mukaisia. Yliopiston lisäkustannuskertoimet tilaustutkimukselle ovat erittäin korkeat, mikä tarkoittaa sitä, että yliopistotutkijat eivät pysty kilpailemaan konsulttifirmojen kanssa. Tilatut projektit rajoittavat myös tutkijoiden luovuutta ja vapautta, koska tutkimusaiheet ja usein myös tutkimuskysymykset ovat etukäteen määriteltyjä. Tämä keskitetty ja kohdistettu rahoitus voi myös aiheuttaa tutkijoille taakan toimittaa mitä heiltä on pyydetty. Mieti seuraavaa esimerkkiä: Jos Liikenne ja viestintäministeriö ajaa tiettyä lakialoitetta (esim. kevytautot), mikä on todennäköisyys, että Traficom rahoittaa projektia, joka suhtautuu kevytautoihin epäilevästi. Ja jos (yliopisto)tutkijan ura/rahoitus riippuu Traficomin rahoituksesta, tämä voi olla hänelle dilemma.

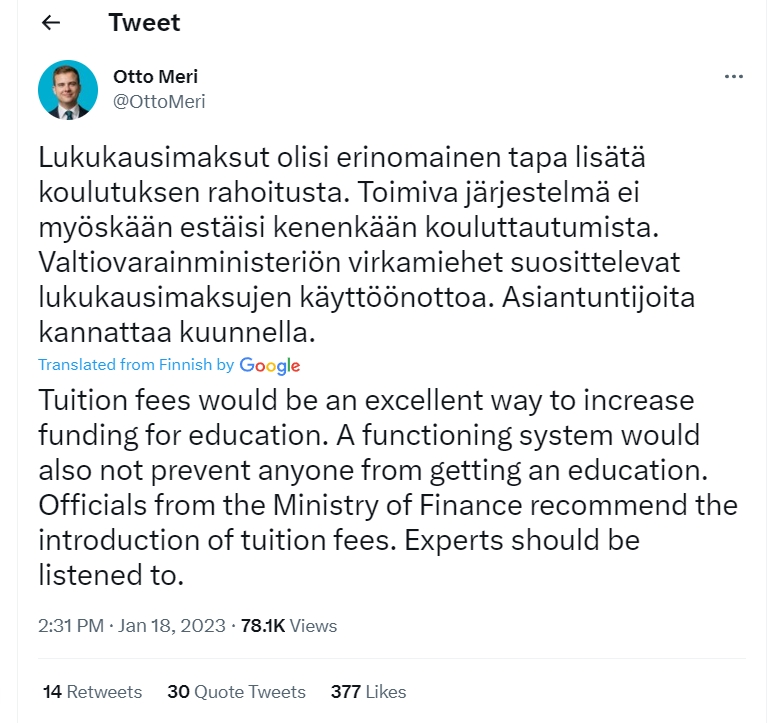

Yliopistotutkijoiden työ ei ole seurata vallalla olevaa poliittista agendaa tai muutakaan ideologiaa. Heidän toimenkuvaansa kuuluu yleisön ja tieteen sanelemien tavoitteiden tutkiminen. Heillä on myös velvollisuus viestittää löydöksensä maailmalle. Konsulttien tekemät tilaustutkimukset julkaistaan lähes aina vain suomeksi, eivätkä ne saavuta kansainvälisen tieteellisen yhteisön tietoisuutta, koska konsulttiyrityksillä ei ole kiinnostusta julkaista tieteellisissä vertaisarvioiduissa julkaisuissa. Vaikka lähes kaikki tilaustutkimus koskee vain Suomea, löydökset ovat kuitenkin kansainvälisesti kiinnostavia ja jaettavissa. Omien menetelmien testaaminen kansainvälisessä tieteellisessä yhteisössä on osa tutkimuksen tekemistä.

Rahoitushaasteiden lisäksi liikennepsykologian professuurien katoaminen tarkoittaa, että liikennepsykologian kurssit on poistettu opinto-ohjelmasta. Kuitenkin monet tulevat psykologit ja lääkärit tulevat kohtaamaan liikenneturvallisuuteen liittyviä aiheita urallaan. Esimerkiksi Psykologiliitolla on lista 161 liikennepsykologista (Psykologi-lehti 2/2020 – katso kuva). Monet psykologit myös työskentelevät valtion organisaatioissa tai valtion rahoittamista organisaatioissa kuten Traficom, OTI, Liikenneturva jne. Tämä tarkoittaa, että koulutus vähenee myös näiden tulevaisuuden asiantuntijoiden kohdalla.

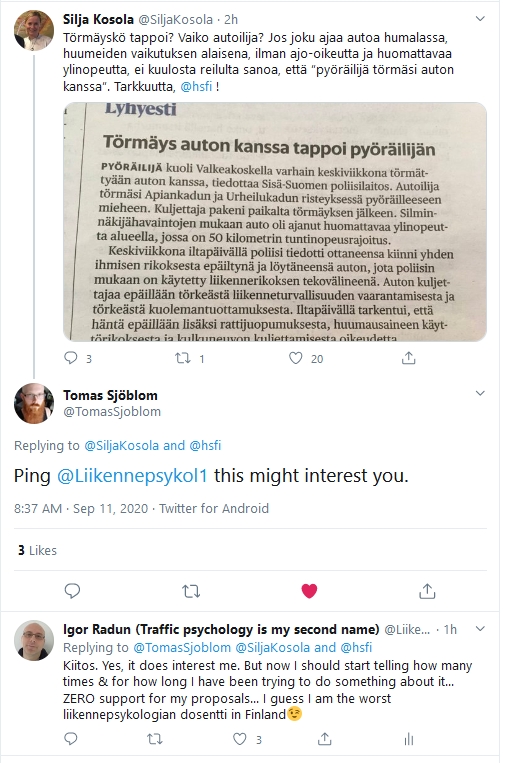

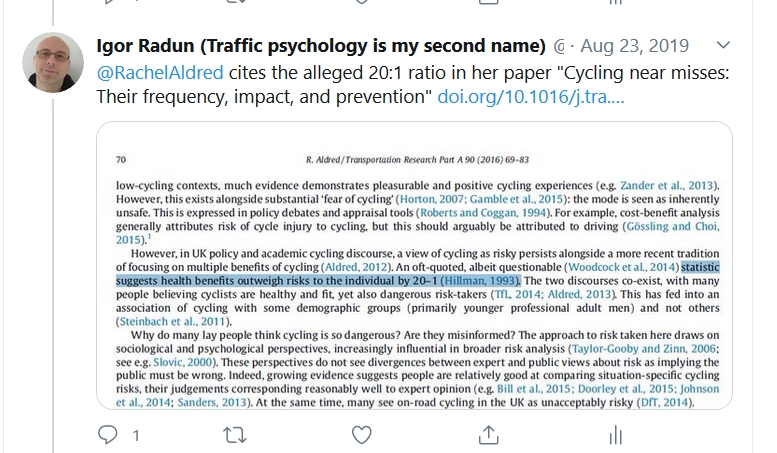

Liikennepsykologian professuurin ja virkaan liittyvien tutkimusryhmien puuttuminen tarkoittaa myös, että kun toimittajat kirjoittavat liikenneturvallisuudesta he eivät voi käyttää riippumattomia yliopistotutkijoita tieteellisen taustatiedon kartoittamiseen ja he tyypillisesti haastattelevat virkamiehiä sekä erilaisten etujärjestöjen edustajia. Usein toimittajat antavat enemmän tilaa sosiaalisessa mediassa esillä oleville ihmisille kuin yliopistotutkijoille (koska heitä ei juuri ole). Tämä voi mielestäni vaikuttaa huomattavasti liikenneturvallisuuteen, erityisesti lisääntyneeseen vihamielisyyteen eri tienkäyttäjäryhmien välillä.

Yhteenvetona, yliopistotutkijat ovat tärkeitä riippumattomia asiantuntijoita, kun ajatellaan tutkimusideoiden luomista, tutkimuksen tekemistä, liikenneturvallisuusmääräysten muovaamista sekä tiettyjen vastatoimien ehdottamista, sekä näiden seurausten tarkastelua. He pystyvät toimimaan lähteinä tasapainoiselle, kriittiselle ja kattavalle katsaukselle ajantasaiseen tieteelliseen kirjallisuuteen. Heidän riippumattomuutensa takaaminen mahdollistaa laadukkaan ja luovan tutkimuksen myös kansainvälisellä tasolla, joka ei riipu sen hetkisistä poliittisista päämääristä tai liikenneturvallisuusmääräyksistä. Kriittinen ajattelu on ensisijaista ja sitä pitäisi varjella yliopistoissa. Tieliikenneonnettomuuksien vaikutus yhteiskunnassa on valtava ja tämän merkityksen tulisi heijastua aiheelle annettuun painoarvoon Suomen yliopistoissa.

Edellä mainituista syistä ehdotan, että ministeriö (joko yksin tai yhteistyössä muiden ministeriöiden kanssa) harkitsee seuraavia ehdotuksia tärkeänä toimena liikenneturvallisuuden parantamisessa Suomessa (esimerkiksi Koti- ja vapaa-ajan tapaturmien ehkäisyn tavoiteohjelmassa):

– Perustaisi riippumattoman, mutta valtion rahoittaman, liikenneturvallisuuden tutkimusinstituutin.

– Lahjoittaisi rahoitusta yliopistoille liikennepsykologian professuureihin tai apulaisprofessuureihin.

– Perustaisi rahoitusohjelman liikenneturvallisuustutkimukselle Suomessa. Puolet rahoituksesta tulisi osoittaa projekteille, joiden aiheet on määritelty suoraan liikenneturvallisuuspolitiikan mukaisesti ja puolet rahoituksesta tutkijoiden itsensä ehdottamille projekteille (vrt. entinen Lintu-ohjelma).

Liite 1.

Koti- ja vapaa-ajan tapaturmien ehkäisyn tavoiteohjelma vuosille 2021–2030 raportin toimittajat sekä asiantuntijaryhmien jäsenet:

Toimittajat:

Ulla Korpilahti, THL

Riitta Koivula, THL

Persephone Doupi, THL

Pirjo Lillsunde, STM

Asiantuntijatyöryhmät:

Lapset ja nuoret

Tieliikenneonnettomuudet:

Mikko Karhunen, yli-insinööri, LVM,

Pia Kola-Torvinen, opetusneuvos, OPH,

Pirjo Lillsunde, neuvotteleva virkamies, STM,

Laura Loikkanen, suunnittelija, Liikenneturva,

Kati Mikkola, opetusneuvos, OPH,

Inkeri Parkkari, johtava asiantuntija, Trafi,

Riikka Rajamäki, erityisasiantuntija, Traficom,

Petteri Tuominen, insinöörimajuri, Puolustusvoimat.

Työikäiset

Tieliikenneonnettomuudet:

Mia Koski, suunnittelija, Liikenneturva,

Matti Koistinen, toiminnanjohtaja, Pyöräliitto,

Jyrki Kaistinen, suunnittelija, Liikenneturva,

Helena Suomela, asiantuntija, Motiva,

Kalle Parkkari, liikenneturvallisuusjohtaja, OTI,

Inkeri Parkkari, johtava asiantuntija, Traficom,

Riikka Rajamäki, erityisasiantuntija, Traficom,

Anne Silla, tutkimuspäällikkö, VTT,

Eija Pyyhtiä, asiantuntija, Helsingin kaupunki,

Heikki Kallio, poliisitarkastaja, Poliisihallitus,

Kristiina Juntunen, lehtori, Jamk,

Henna Nikumaa, vanhuusoikeuden yliopisto-opettaja, UEF,

Jari Lepistö, pelastusylitarkastaja, SM,

Kai Valonen, johtava tutkija, OTKES,

Igor Radun, yliopistotutkija, HY,

Noora Airaksinen, apulaisosastopäällikkö, Sitowise,

Maija Rekola, erikoisasiantuntija, LVM, Mirjami Silvennoinen, asiantuntija, Helsingin kaupunki.

Iäkkäät

Tieliikenneonnettomuudet:

Mia Koski, suunnittelija, Liikenneturva,

Matti Koistinen, toiminnanjohtaja, Pyöräliitto,

Jyrki Kaistinen, suunnittelija, Liikenneturva,

Helena Suomela, asiantuntija, Motiva,

Kalle Parkkari, liikenneturvallisuusjohtaja, OTI,

Inkeri Parkkari, johtava asiantuntija, Traficom,

Riikka Rajamäki, erityisasiantuntija, Traficom,

Anne Silla, tutkimuspäällikkö, VTT,

Eija Pyyhtiä, asiantuntija, Helsingin kaupunki,

Heikki Kallio, poliisitarkastaja, Poliisihallitus,

Kristiina Juntunen, lehtori, Jamk,

Henna Nikumaa, vanhuusoikeuden yliopisto-opettaja, UEF,

Jari Lepistö, pelastusylitarkastaja, SM,

Kai Valonen, johtava tutkija, OTKES,

Igor Radun, yliopistotutkija, HY,

Noora Airaksinen, apulaisosastopäällikkö, Sitowise,

Maija Rekola, erikoisasiantuntija, LVM,

Mirjami Silvennoinen, asiantuntija, Helsingin kaupunki.