The media are often criticized for the way they report on crashes involving cyclists. So-called victim blaming is the central accusation. In this blog post, I discuss the text ‘Motorists Punish Helmet-Wearing Cyclists With Close Passes, Confirms Data Recrunch’ written by Carlton Reid, ‘the Press Gazette Transport Journalist of the Year 2018,’ and the famous Ian Walker ’s study on which Reid’s text is based.

Walker’s 2007 study

One of the most famous studies in cycling research is Ian Walker’s “Drivers overtaking bicyclists: Objective data on the effects of riding position, helmet use, vehicle type and apparent gender ” from 2007. In this study, Walker, the main investigator, was riding a bicycle with a helmet or without it. The study reported that “wearing a bicycle helmet led to traffic getting significantly closer when overtaking.” The difference was “around 8.5cm closer on average.”

This finding received large attention from the research community as well as from the media and general public. It is often cited in support of risk compensation (motorists unknowingly (?) rate cyclists without a helmet as more inexperienced and unpredictable and thus keep greater distances to them). It is also used as an argument against bicycle helmet laws and/or promotion of bicycle helmets as the ‘obvious’ conclusion from this study is that helmets put cyclists at greater risk posed by motor vehicle drivers.

Olivier and Walter (2013) reanalysis of Walker’s data

In 2013, Olivier and Walter reanalyzed Walker’s data, which he had generously posted online. [This is something for which Walker deserves huge credit] Olivier and Walter dichotomized the passing distance by the one meter rule and carried out a logistic regression, while in the original analysis Walker (2007) applied an analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the raw data (with a square-root transformation). Olivier and Walter wrote: “The previously observed significant association between passing distance and helmet wearing was not found when dichotomised by the one metre rule.” Their conclusion was that “helmet wearing is not associated with close motor vehicle passing.”

Walker and Robinson (2019) response to Olivier and Walter (2013)

Walker and Robinson published their rebuttal in Accident Analysis and Prevention in 2019, the same journal where the original Walker study had been published (Olivier and Walter, 2013, paper was published in PlosOne). They criticized Olivier and Walter on several accounts: “Their conclusion was based on omitting information about variability in driver behaviour and instead dividing overtakes into two binary categories of ‘close’ and ‘not close’; we demonstrate that they did not justify or address the implications of this choice, did not have sufficient statistical power for their approach, and moreover show that slightly adjusting their definition of ‘close’ would reverse their conclusions.”

My view about Walker (2007) study

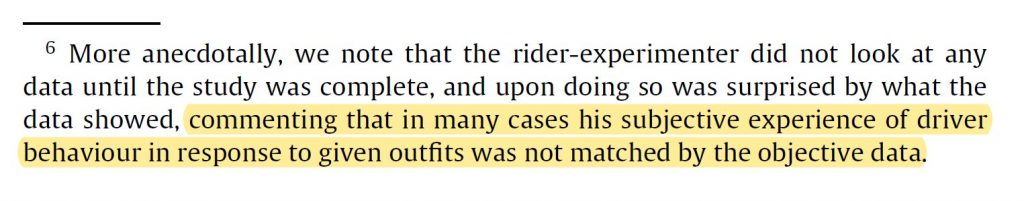

1. The experimenter effect. Ian Walker was the single author and experimenter in this study. He had a clear hypothesis and expectations. Furthermore, we could assume he was observing how close the motorists overtake him in the relation to his hypothesis as another single-experimenter reported doing so in another similar Walker’s study (see below). This raises a question whether the behavior of the riders arising from their hypotheses and subjective experiences while the experiment was going on had any effect of the behavior of the naïve participants (i.e., motorists).

We (Radun and Lajunen, 2018) discussed the study design in the context of the experimenter effect. We wrote: “Although drivers were effectively blind to the study, the experimenter was not. Consequently, his hypothesis could have caused him to behave in ways that influenced overtaking distances, for example, by making head movements suggesting an intended turn, which might have prompted drivers to give him a wider berth.”

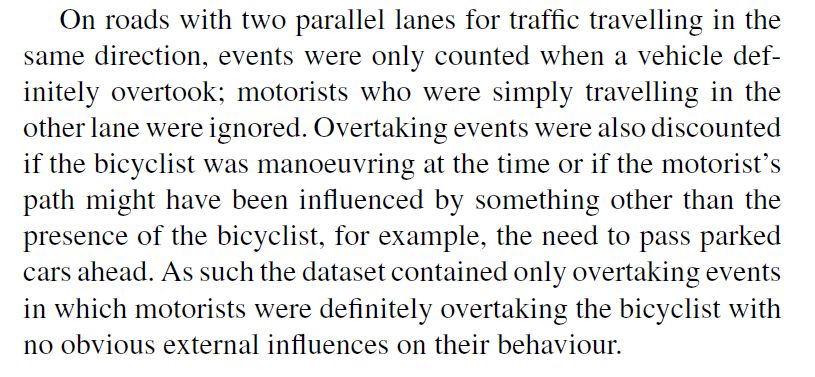

2. The observer bias. It seems some of the overtaking events were discounted based on the video analysis. However, it is unclear who has performed this selection and how many events were excluded. Typically, two observers should independently analyze all events, compare their results and discuss possible discrepancies. Walker has not thanked anyone for this work in the paper’s Acknowledgements, which makes me wonder whether a fully informed experimenter/author was the only observer making the selection, which of the events should be excluded and which should remain in the data set. Please note that the observer bias as well as the experimenter effect do not imply any deliberate action. Neither do I in this text.

3. Never replicated. To my knowledge, the main finding (i.e., drivers overtake closer when a cyclist wears a helmet) has never been replicated in another setting or country.

4. One meter vs. 1.5m rule. Walker and Robinson criticized Olivier and Walter for their choice to dichotomize the passing distance by the one meter rule. They write: “if we want to use existing legislation as a guide to separating close from not-close events, we should at least use the 1.5m rule mandated in Spain and Germany (road.cc, 2009; Spanish News Today, 2014) and place the burden on proof on those who would suggest a closer distance to define safety.”

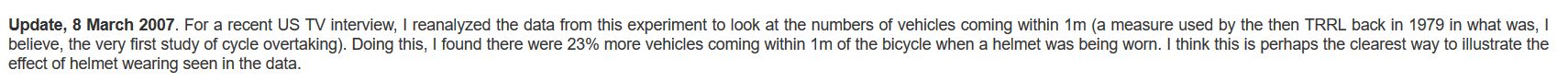

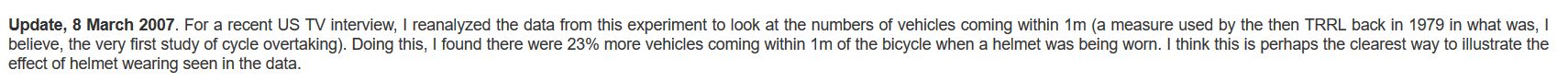

However, they somehow forgot to cite an old TRRL study that used “the numbers of vehicle coming with 1m” and inspired Walker to reanalyze his data for an US TV interview in 2007 by using the same 1m rule (see below a snapshot from Walker’s old webpage).

It seems somewhat unfair to criticize Olivier and Walter of not justifying their choice of using the 1m rule while ignoring the fact that Walker in 2007 thought that “this is perhaps the clearest way to illustrate the effect of helmet wearing seen in the data.” Furthermore, one would think that the previous study from the same setting (e.g., traffic culture, roads’ width etc.) would be at least as relevant as the German and Spanish 1.5m rule Walker and Robinson cite. I don’t want to speculate about why Walker and Robinson failed to cite this older UK study.

5. Statistical vs. clinical significance (i.e., closer vs. close passes). The main issue of dispute between these researchers is about what is to be considered as a close pass (and methodological and statistical consequences of a particular choice) and whether the observed difference of 8.5 is a reason for concern. Walker and Robinson write “The W7 dataset at least hints that the probability of a trip transitioning from the large pool of un-eventful journeys to the smaller pool of journeys with a collision might increase owing to changes in driver behaviour in response to seeing a helmet. This merits caution until further data can be obtained.”

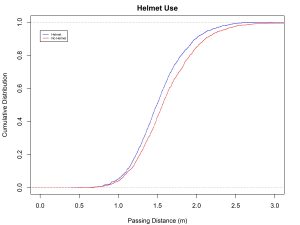

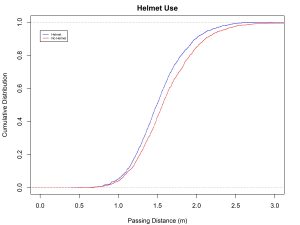

Below is a figure with the empirical distribution for passing distance (helmet vs. not). They’re nearly identical towards 0 (i.e., a likely crash) and don’t separate until after 1m.

6. In conclusion. Although I don’t dispute the reported 8.5cm difference, Walker’s experimental design was far from perfect because he was a fully informed experimenter interacting with his participants (i.e., motorists) and as it seems the only observer who pre-selected the data for further analysis. Furthermore, to my knowledge this finding has never been replicated (the study was published in 2007). I wonder whether a single never-replicated UK-study with a single fully informed experimenter/observer should be used to scare people around the globe of not wearing a bicycle helmet. I wonder.

Carlton Reid’s ‘Motorists Punish Helmet-Wearing Cyclists With Close Passes, Confirms Data Recrunch’.

Now I describe one of the most scandalous examples of scaring people by an award winning transport journalist in the context of above mentioned studies.

1. The misleading and malicious title (“Motorists Punish Helmet-Wearing Cyclists With Close Passes, Confirms Data Recrunch”). In my view, this represents a scandalous attempt to scare people of using a bicycle helmet. The verb ‘punish’ used in this context implies a deliberate action. Walker (2007) study provides no evidence that motor vehicle drivers deliberately give less space to helmeted cyclists.

Furthermore, it is incorrect that “Motorists Punish Helmet-Wearing Cyclists With Close Passes” because Walker (2007) and Walker and Robinson (2018) do not describe the reported overtaking difference as close passes. As discussed above, they report that motor vehicle drivers overtake cyclists with a helmet closer (!) with an average of 8.5 cm than those without a helmet. This difference of 8.5cm does not necessarily imply any of the overtaking events should be considered as a close pass. As Ian Walker told Carlton Reid “He claims that Olivier and Walter were only able to disprove his study by redefining what was meant by the words ‘close’ and ‘closer.’” Carlton Reid obviously ignores this and insists that closer (i.e., 8.5cm) means “a close pass.”

2. The failure to interview the other party. Carlton Reid has interviewed Ian Walker for this article. As he interviewed Walker after the original study had appeared eleven years ago. To my knowledge, Reid has never attempted to interview Jake Olivier and Scott Walter since their study had been published in 2013.

Ian Walker said in this new interview: “It’s notable that the university research group [which wrote the 2013 paper and others] seem very interested in rebutting any suggestions that cycle helmets are not a panacea for safety,” remarked Walker.”

It is obvious that Ian Walker not only questioned Olivier and Walter, 2013 paper, he also questioned their motives (“seem very interested in rebutting any…”). This is a clear attack on their research integrity. According to good practices of journalism, Carlton Reid should have asked Olivier or Walter for their comments. It is unusual that researchers question each other motives in an interview. When that happens, it is an absolute must to interview the other party and give them an opportunity to respond to such questioning. To my knowledge, Carlton Reid has never done that. Actually, it seems he was so eager to publish his text as it appeared online only a few hours after Walker and Robinson paper had been published online as a preprint.

The preprint was posted online on November 14, 2018

Carlton Reid’s text appeared online Nov 14, 2018, 05:01pm

This clearly shows Carlton Reid had no intention to interview the ‘other party’.

3. “Other academics agree.” Implying that other academics agree (“Other academics agree”) with something Ian Walker said by mentioning only one academic is so wrong that I believe no further comment is necessary.

The Active Travel Academy’s inaugural Media Awards

Because of the above reasons, I nominated Carlton Reid for The Active Travel Academy’s “People’s choice awards: A. Worst reporting on TV/Radio, print or online”

This award “celebrates the work of journalists and reporters covering issues across media outlets around active transport and road safety in the UK.” In addition to my nomination, Carlton Reid was shortlisted for another category (“1. News (written word))” for another of his texts.

I am not sure whether People’s choice awards have been awarded as this category is no longer visible on the Active Travel Academy’s webpage. I have repeatedly asked Active Travel Academy’s “expert panel of judges” about this on Twitter but they have never responded.

It is also interesting that although the awards cover not only active transport issues but also road safety in general, the “expert panel of judges” includes, in addition to several academics, representatives from cycling and pedestrian organizations, however, no one from any motorist organization. To my knowledge, traffic safety issues and how they are represented in media is also of interest to motorist organizations.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the media has a lot of power when it comes to disseminating scientific knowledge. Given the above discussion surrounding Walker’s 2007 study and subsequent re-analyses, Carlton Reid’s article, in my view, represents an awful piece of journalism. I am not fully familiar with his work but one would expect a more balanced text given that he is after all ‘the Press Gazette Transport Journalist of the Year 2018,’ and obviously respected by the Active Travel Academy’s “expert panel of judges” as they shortlisted his another text for one of their awards.

I have recently proposed an EU project that would gather all interested stakeholders (researchers, journalists, police, advocacy groups etc.) in several workshops in order to produce a guideline for journalists about how to report on crashes including cyclists as this issue produces a lot of discussion. Similar guideline for the media, although for different reasons, exists about suicides (“Suicide Prevention Toolkit for Media Professionals”). Unfortunately, I have not received funding for it. I hope more qualified and suitable researchers will get funding for similar project and that in the near future they will produce a good guideline for the media. Before that happens, we will see more of Reid-like articles. Unfortunately.