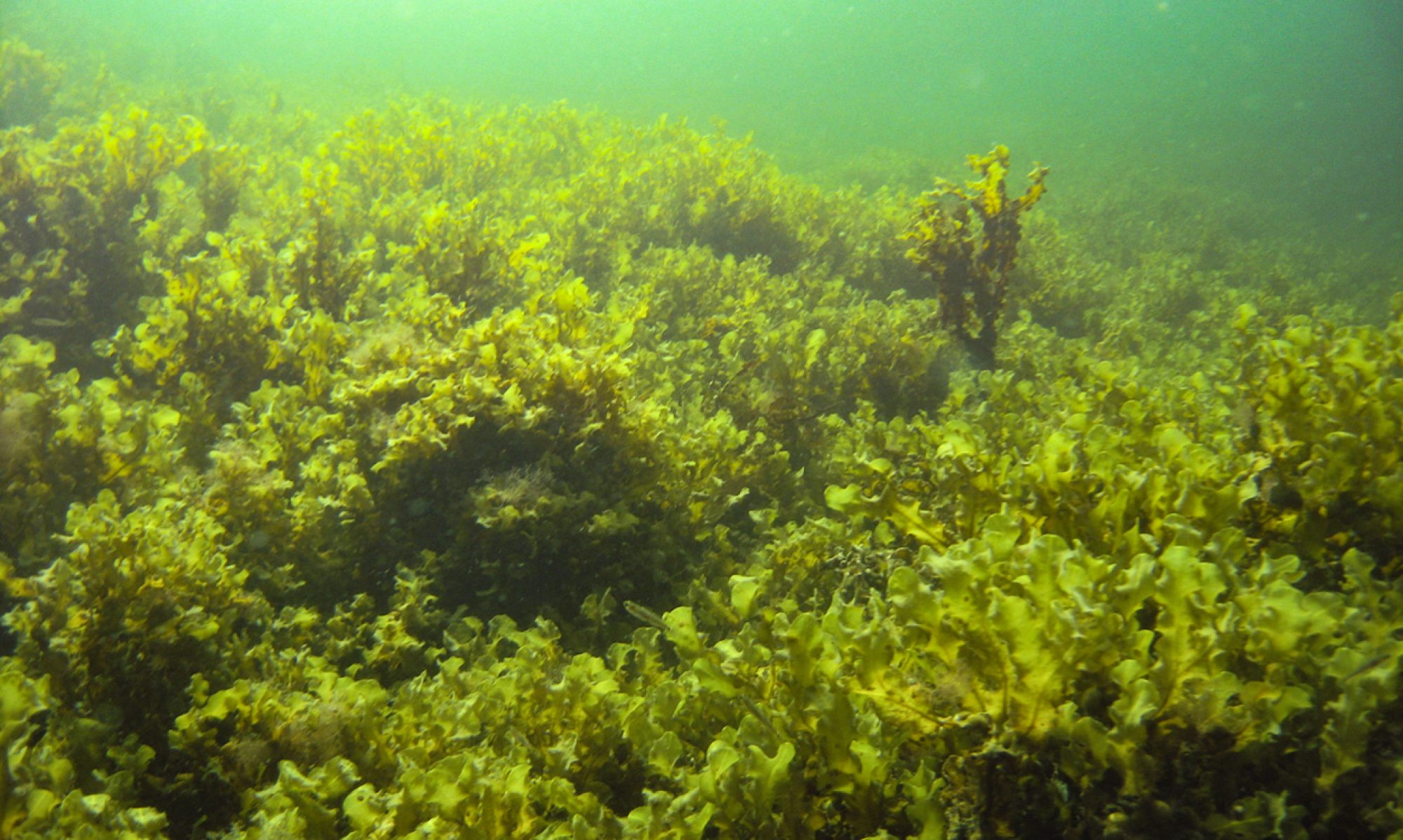

Seaweeds can often be found along the borders between land and sea; better known as the coast. Seaweed can be found in these coastal locations as either either have permanent inhabitants, such as the intertidal seaweeds, or beach debris where pieces of seaweeds are washed ashore by waves and tides.

Green (Ulva spp) and brown (Fucus spp) seaweed at low tide. Saltdean. East Sussex. UK.

As borders between land and sea, coastal locations can often be important transitional zones for animals to supplement their diet. Polar bears, wolves and brown bears are well known to appreciate the bounty of a stranded whale carcass washed upon the shore (Lewis & Lafferty, 2014; Laidre et al., 2018).

It is not just carnivores that benefit from the sea’s bounty though. In the isolated Svalbard archipelago, located 800km north of mainland Norway in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, well north of the Arctic Circle, coastal seaweed is becoming an important resource in the face of climate change.

Longyearbyen. Svalbard.

Warming temperatures in the archipelago are creating more frequent rain on snow conditions, whereby thick layers of ice cover the land vegetation, including mosses and lichens. These impenetrable ice-locked pastures make foraging for food difficult for Svalbard’s herbivorous animals. Including the Arctic’s most famous grazer, the reindeer.

Reindeer. Svalbard.

Svalbard’s reindeer (Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchu) is a peculiar type, thanks to its unique habitat. They are shorter and stockier than mainland European and north American reindeer, being well suited to the cold of the far north. Unlike their mainland relatives Svalbard reindeer do not show migratory behaviour, instead they could be considered rather lazy, being characterized by a stationary, energy‐saving lifestyle. This lifestyle is only possible in Svalbard by virtue of the unusual lack of predation. The Svalbard reindeer population is instead controlled by climate and density dependent processes, with starvation being the most common cause of death.

Reindeer. Svalbard.

With the availability of food being a very important factor effecting survival, the increasing occurrence of ice-locked pastures could pose quite fatal for Svalbard reindeer.

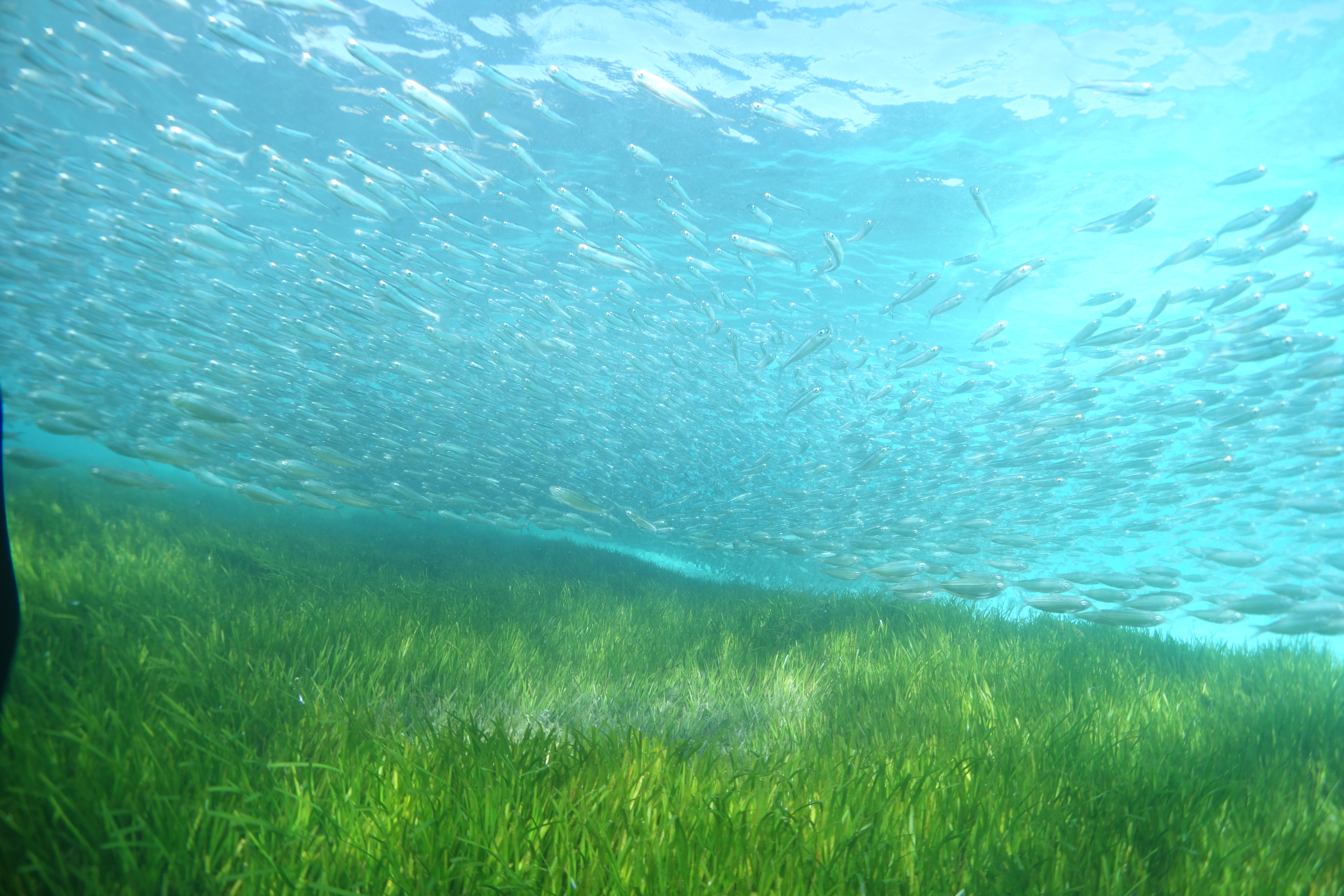

But some have come up with a clever coping mechanism. On the northwestern coast of Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago, 13% of the total reindeer population turned to the coast for food (Hansen and Aanes, 2012). They were found to developed a taste for eating kelp and other seaweeds that had been washed ashore.

However the reindeer cannot sustain themselves entirely on seaweed, being observed to frequently move between beaches and more accessible pastures. The seaweed scraps were being used as an exotic supplement to the reindeer’s normal plant‐based diet.

By adjusting their behavioural the reindeer utilise resources of sea origin to help survival during harsh winters. With the prediction of far more frequent harsh winters due to climate change, seaweed could act as a vital buffer in the face of environmental variation.

And Svalbard reindeer are not unique, many other herbivores eat kelp or seaweed too. From the sheep (Ovis aries) on Orkney [Scotland] (Hall, 1975), red deer (Cervus elaphus) on the Isle of Rum [Scotland] (Conradt, 2000), to black‐tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus) of channel island [Alaska] (Parker et al., 1999).

Sheep feeding on seaweed along the shoreline. North Ronaldsay. Orkney. Scotland.

So seaweed is not just important in the sea world, it could be helping many land species too, especially in the face of climate change.

This post was based on the research of Hansen et al., (2019). If you enjoyed this post you can find the open access article here:

Sources:

Conradt, L. 2000. Use of a seaweed habitat by red deer (Cervus elaphus L.). Journal of Zoology 250:541–549.

Hall, S. J. 1975. Some recent observations on Orkney sheep. Mammal Review 5:59–64.

Hansen, B. B., and R. Aanes. 2012. Kelp and seaweed feeding by High‐Arctic wild reindeer under extreme winter conditions. Polar Research 31:17258.

Laidre, K.L., Stirling, I., Estes, J.A., Kochnev, A. and Roberts, J., 2018. Historical and potential future importance of large whales as food for polar bears. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16(9), pp.515-524.

Lewis, T.M. and Lafferty, D.J., 2014. Brown bears and wolves scavenge humpback whale carcass in Alaska. Ursus, International Association for Bear Research and Management 25(1), pp.8-13.

Parker, K. L., M. P. Gillingham, T. A. Hanley, and C. T. Robbins. 1999. Energy and protein balance of free‐ranging black‐tailed deer in a natural forest environment. Wildlife Monographs 143:3–48.