Authors: Luca De Magistris, Irene Milani, Vivian Schwarzwälder

Among all the Central Asian countries that once were part of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan is still heavily affected by Russian influence in many regards. This is reflected in the complexity of the language debate, which, since its outset in the 1980s (Fierman, 1998, p. 175), unfolds in different ways and in different realms that are not merely linguistic. At the bottom of the debate lies article 7 of the Constitution of Kazakhstan which states that Kazakh is recognized as the “state language”, whilst Russian, its “colonial language”, “shall be officially used on equal grounds along with Kazakh”[1]. Even though the wording is vague (Fierman, 1998, p. 179), both languages are coexisting due to many reasons, for instance, the geographic proximity, or the demographic distribution of ethnic Russians. In addition, Kazakhstan values greatly its economic relations with Russia, therefore Kazakhs still see Russian as the language to learn for economic growth and opportunities.

With that said, Kazakhstan has not been immune to the de-russification trends affecting the post-communist space. After 1991, Kazakhs have slowly grown as the ethnic majority in the nation (Bureau of National Statistics, 2009; 2021), with a parallel growth in the interest in the Kazakh language and culture. However, these developments should be recontextualized under the unfortunate circumstances of the ongoing war. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Kazakh language shift becomes more significant if regarded as a conscious choice bearing political meaning.

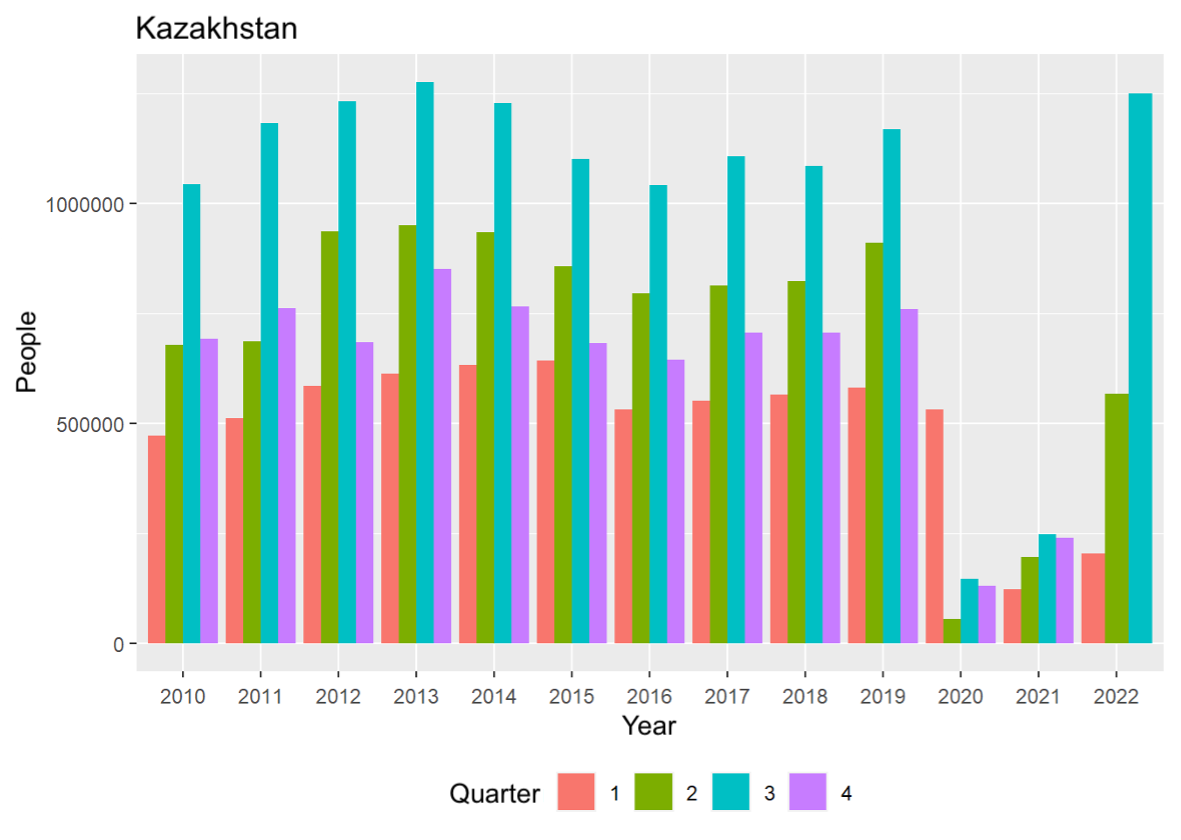

As the war persists, so do the changes in the attitude of Kazakhstan toward its titular language. Very recently there have been some developments coming from the upper echelons of Kazakhstan, whose stance in the Russian-Kazakh language debate completely capsized. During a CIS summit in October, 2023 was declared to be the “Year of the Russian Language as a Language of Interethnic Communication in the CIS”[2]. As hollow as such a declaration might be, it still retains a strong symbolic significance: if framed in the post-February 24th political climate, such statements could be read as supporting one side instead of the other, even if this might not reflect Kazakhstan’s actual stance regarding the war. While people on social media were still debating over Ramil Mukhoryapov’s controversial statement linking Kazakh with nationalist sentiments[3], things suddenly took a different turn. The government proposed draft legislation to make knowledge of the Kazakh language a requirement to obtain citizenship. While this may seem unexpected, the draft seems to represent a securitization move to counterbalance the mass flow of Russian citizens arriving in Kazakhstan because of the war and the subsequent partial mobilization. Statistics from ЕMISS show that 1.25 million people entered Kazakhstan between July and September alone (Figure 1), and the concern over this data clearly emerges in Prime Minister Smailov’s address to the Parliament, in which he proposes the aforementioned draft[4].

Figure 1: Russian citizens that moved abroad [Выезд граждан России за рубеж], EMISS, November 2022

These changes in the state-promoted language planning emerge as erratic when compared with the grassroots sentiment towards Kazakh. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the gradual detachment from Russia—including its culture, language, and traditions—was a predictable trend in those countries that suddenly gained independence. The pace of this de-russification trend was certainly slower in Kazakhstan, but still, it was a steady process that found its exponential growth only in recent years. Some attempts have been made, such as the project “The functioning and development of languages of Kazakhstan for 2011-2020” (Aksholakova & Ismailova, 2013, p. 1581); but the protection of Kazakh was always accompanied by a warning not to abandon Russian as the language of opportunities. However, if at first there have been joint efforts to make the two languages coexist, things have started to change in the wake of this year’s events.

After February 24th, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, anti-war demonstrations sprung all around the world. People have been engaging in different acts of protest and, while many people took it to the streets, gathering in front of Russian embassies in different cities, others chose to take a stand in less manifest ways. Symbolic public acts, such as the display of symbolic images, or wearing certain colors, are a common non-violent way of protesting. Although it depends on the circumstances, even the language one chooses to use in day-to-day communication can be considered as a political stance, a non-conventional way of resistance. This take is particularly relevant when it comes to Kazakhstan.

What we noticed is that, after the war, there has been a shift in the intent that lies behind the “kazakhization”, (Smagulova, 2008): people are “rallying around their language” and are now actively choosing to speak (or learn) Kazakh as a political act against Russia’s supremacist actions and the hegemonic use of the Russian language in Kazakhstan.

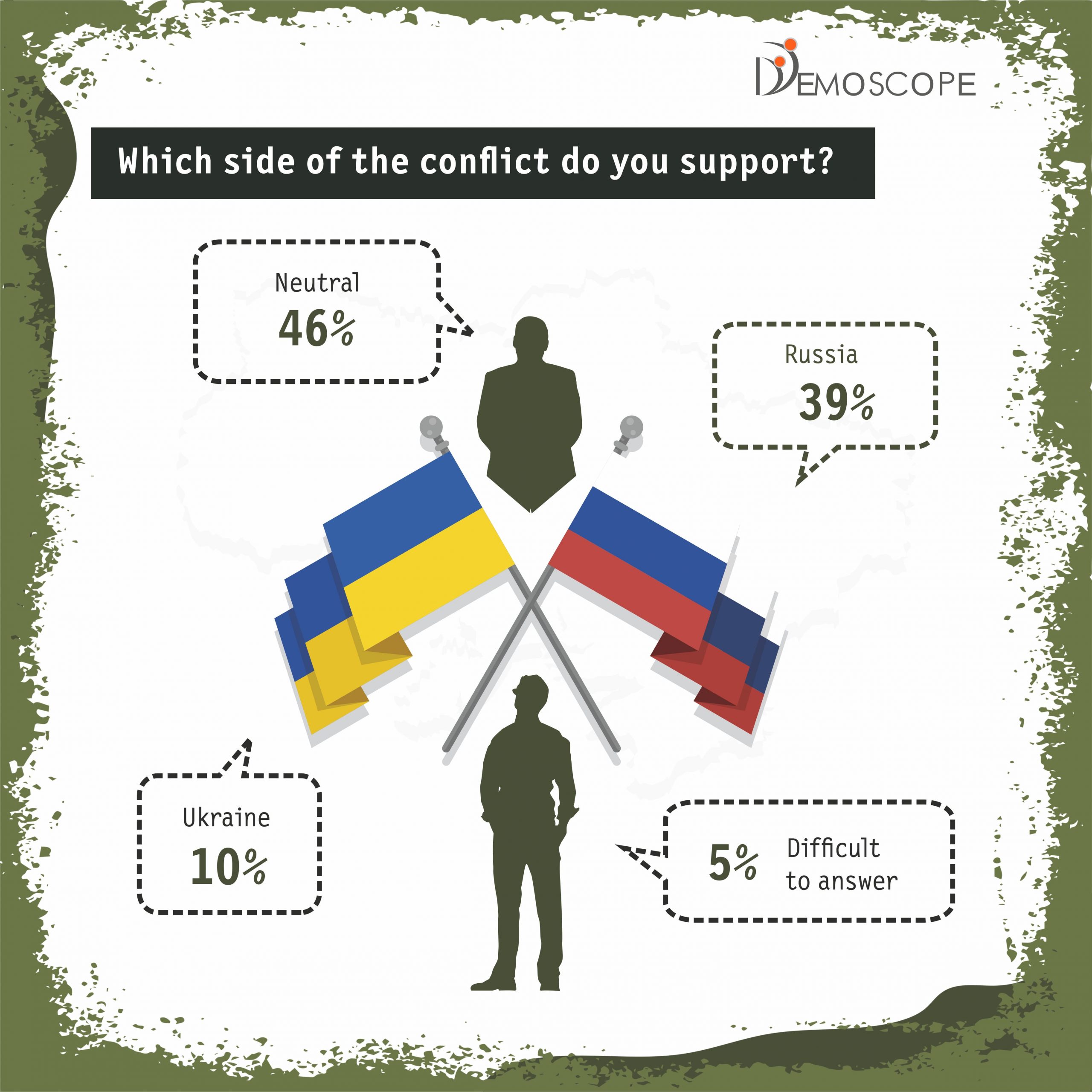

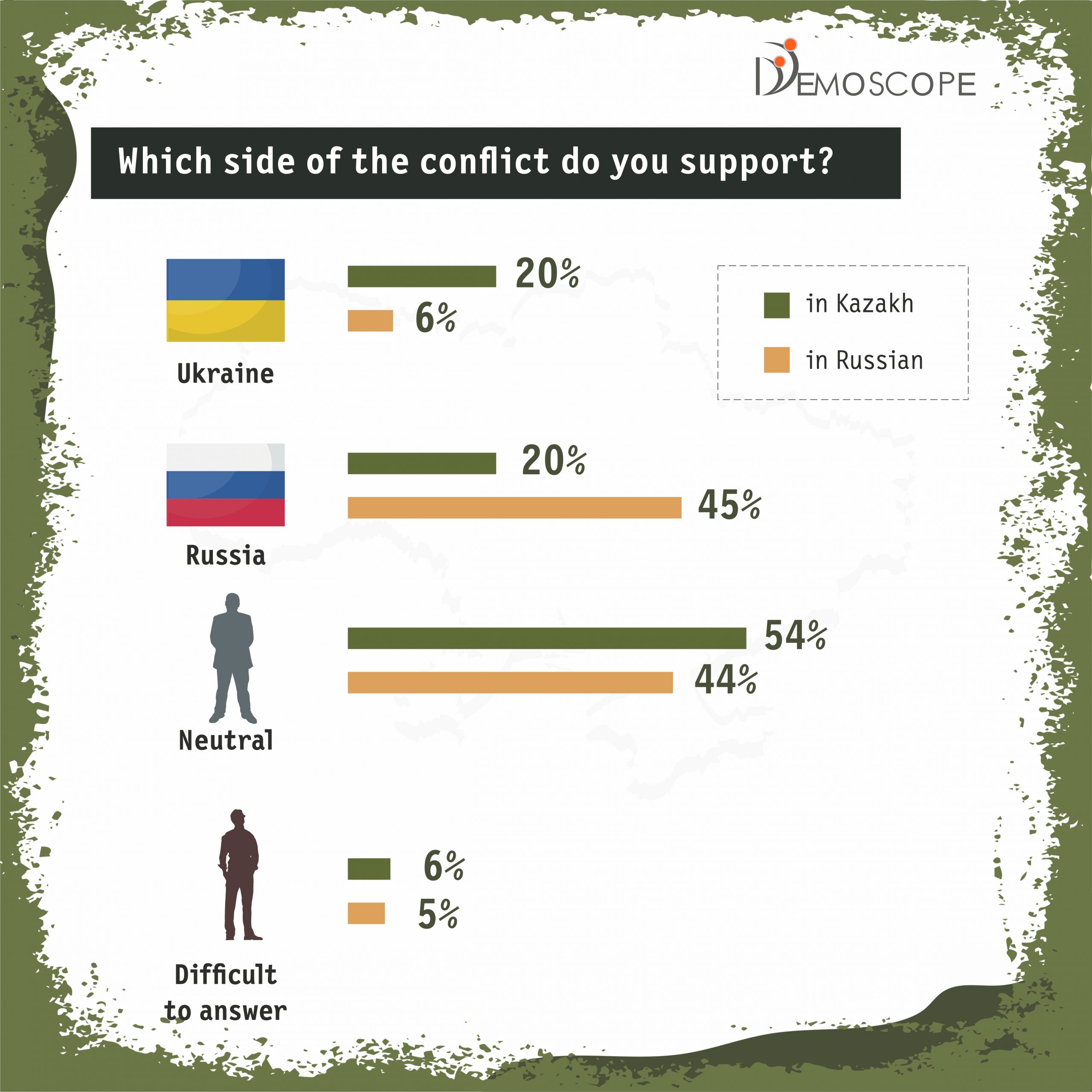

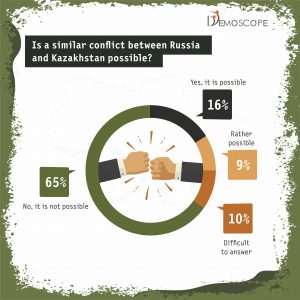

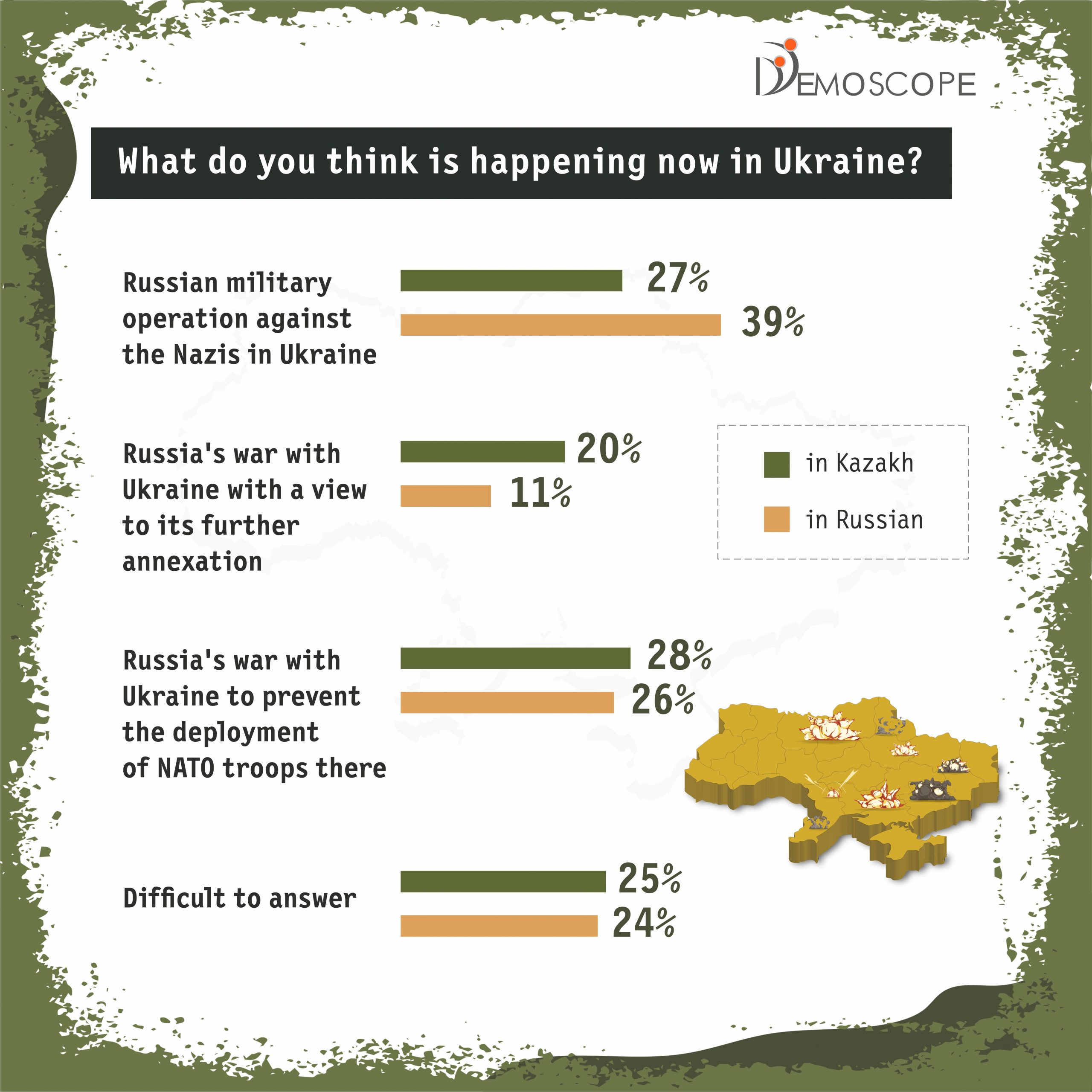

A survey conducted by Demoscope in April 2022 confirms that there is a correlation between how Kazakhs feel about the war in Ukraine and the language they speak (Figures 2-7). The survey did not take into account language per se, as the questions were mainly about the war, and they seem to support the idea of Kazakhstan still being loyal to Russia. However, the pollster provided a comparative view of the same data, which leads to a completely different interpretation. Since Demoscope published the percentages of people who responded either in Kazakh or Russian for each answer, it is possible to draw some conclusions on people’s attitudes towards Russia, based on the language they chose. For instance, those who chose to respond in Kazakh, albeit only 23% of the total respondents, showed clearly different sentiments towards the war. They are considerably more neutral than those who chose to respond in Russian, who also exclude any possibility of a similar conflict starting between Russia and Kazakhstan. This survey helps to visualize in numbers those grassroots and bottom-up attitudes towards Kazakh and Russian, which have often translated into initiatives to promote the Kazakh language. These initiatives, such as language clubs, forums, and digital developments, along with the general sentiment that we have observed on social media, all concur with the strengthening of the Kazakh civil society in the name of national identity and titular language.

Figures 2-3: Which side of the conflict do you support?, Demoscope, April 2022

Figures 4-5: Is a similar conflict between Russia and Kazakhstan possible?, Demoscope, April 2022

Figures 6-7: What do you think is happening now in Ukraine?, Demoscope, April 2022

Our analysis is not founded on the claim that language and political identity are one and the same. Speaking Kazakh does not automatically imply being anti-Russia, just as much as speaking Russian does not equate to being anti-Ukraine. Language is primarily the vehicle through which discourses, ideas, and thoughts are expressed, ergo changing the how does not necessarily change the what. However, the sudden language shift in Kazakhstan still holds some political significance because of the circumstances in which it occurred. Changes in political discourse do not necessarily imply changes in language choice; still, further research on the correlation between language and discourse could benefit from other factors such as the language of education, news sources, or media in general.

On a final note, if in many parts of the world, the correlation between language and politics is rather straightforward, when it comes to post-communist countries it often takes many different forms. The peculiar case of Kazakhstan shows that resisting the hegemony of the colonial language, especially if it is still entrenched in the nation after so many years of independence, assumes great political significance. Hence, given the current political climate, it is important to recognize the choice of speaking and learning Kazakh for what it is: a way of reclaiming national identity.

[1] Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 1995, available at https://www.akorda.kz/en/official_documents/constitution

[2] http://www.kremlin.ru/supplement/5856

[3] During a meeting, the highly influential businessman claimed that speaking Kazakh to Russian people is a “display of nationalism” [«проявление такого чуть-чуть национализма»] and it is not “derivative of great culture” [«это не от большой культуры»]. The video of the incident is available at https://vk.com/wall-31643537_7454231?lang=en

[4] Prime Minister Smailov’s response to Parliamentary Inquiry DC-278, 3 November 2022, available at https://parlam.kz/en/mazhilis/question-details/19001

The conference consisted of six panels and two roundtable discussions, with participants traveling from Europe and North America, as well as joining online.

The conference consisted of six panels and two roundtable discussions, with participants traveling from Europe and North America, as well as joining online.

His name is Viktor Lambin and he is a Doctoral Student, at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki.

His name is Viktor Lambin and he is a Doctoral Student, at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki.