BY DR. RUSTAMJON URINBOYEV

In a new blog post on prisons during the pandemic, Dr. Rustamjon Urinboyev turns to the experiences of Muslim prisoners in contemporary Russia. Drawing on his extensive fieldwork among migrants from Uzbekistan who have served prison sentences in the Russian Federation, he analyses the everyday practices of these transnational prisoners and their prison communities, and explains how these practices have changed since the onset of coronavirus-related lockdowns.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already brought about dramatic and unprecedented consequences across the globe, particularly affecting marginalized groups such as prisoners whose livelihood, health and welfare are heavily dependent on the availability of daily contact with the “outside” world. As the number of confirmed coronavirus cases started to increase, Russia, in parallel with many other countries around the world, introduced strict lockdown measures to contain the virus. Considering the fact that prison populations are particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic, Russian authorities have completely closed prisons and correctional colonies and suspended all visits to prisoners until further notice.

There are large numbers of foreigners in Russian prisons and correctional colonies. As Russia receives millions of migrant workers from other post-Soviet countries (predominantly from Central Asia), Russian penal institutions have already become ethnically, culturally and religiously diverse, hosting large numbers of foreign prisoners. The majority of these foreigners are Muslims (Uzbeks and Tajiks) from two Central Asian republics, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It is reasonable to assume that Muslim prisoners have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in very specific and potentially discriminatory ways due to the strict lockdown of penal institutions. The end of visits from their migrant networks and relatives, the restriction of the daily flow of information, money, electronic devices, halal meat, food and produce parcels (because they generally came from the outside) could dramatically change many facets of the lives of Tajik and Uzbek Muslims prisoners. The immediate effects might have included the ability of prisoners to practice religion in groups (jamoat), and could have also changed their socializing and fast-breaking events during the Ramadan period. The lockdown measures may also have affected the power geometry within colonies, changing the relationship between the prison administration and prisoners, as well as between Russian and foreign prisoners. On the other hand, considering the power and influence of prison subcultures, especially in the so-called “black colonies” controlled by criminal authorities, it can be assumed that restrictions have only taken place in theory and not in practice, in which case we are fearful for the health and welfare of the prisoners because the conditions in prisons are ideal for the virus to spread.

One main reason for posing these speculative questions is that there has been a complete blackout of information from the side of the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN). It is nearly impossible to receive information about what is happening inside Russian prisons and correctional facilities to Muslim prisoners from Central Asia and the Caucasus, who are more vulnerable than local prisoners. FSIN continuously claims that relatively few prisoners have caught the virus. But human rights watchdogs have faced restrictions in gaining access to prisons, if they have not been excluded from visits altogether. Given the absence of credible information about COVID-19- and its effects on Russian penal institutions, we will probably know the true impact when all lockdown restrictions have been lifted.

Considering these recent developments in Russian penal institutions, in this blog post I will try to understand and explore whether and how COVID-19 affected the health, rights and psychological conditions of Muslim prisoners from Central Asia. In the first part of the blog post, I will present contextual information about Central Asian Muslim prisoners. Next, I will present empirical examples from my recent fieldwork which describes the situation and everyday lives of Muslim prisoners in pre-COVID times. I argue that we cannot fully understand the effects of COVID-19 on prisoners’ lives in Russian prisons without knowing the the situation of the prisoners in non-COVID times. The post concludes with some empirical examples and reflections on the effects of COVID-19 on Russian penal institutions in general, and on the daily life of Muslims prisoners in particular. The empirical material presented in this blog is based on my own recent fieldwork in the Fergana Valley of Uzbekistan, which involved ethnographic interviews with Uzbek ex-prisoners who served sentences in different Russian penal institutions.

Russia as a key immigration hub in the post-Soviet space

Russia has become one of the main migration hubs worldwide following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The vast majority of migrant workers come to Russia from three Central Asian countries—Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. In 2019, there were more than two million Uzbek nationals, more than one million Tajik nationals, and about 700 thousand Kyrgyz nationals in Russia (these are all approximate numbers). Men constitute 80 to 90% of migrants from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, whereas almost half of the migrants from Kyrgyzstan are female. The “average” Central Asian migrant, if taken in statistical and demographic terms (with all the limitations this kind of generalization has) is a young male with a secondary education and a poor command of the Russian language, originating from the rural areas or small towns of Central Asia where unemployment rates remain exceptionally high. Central Asian migrants primarily work in construction, trade, transportation, service, agriculture, and housing and communal services.

As Russia maintains a visa-free regime with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), almost all migrants from Central Asia enter Russia legally. However, Russian immigration laws and policies are ambiguous, inconsistent and contradictory, which makes it nearly impossible for Central Asian migrants to be “fully legal”, or documented, in Russia. As a result, millions of migrants are compelled to work in the shadow economy, where they can survive without immigration documents. However, shadow economy employment often puts migrants in a disadvantaged and precarious position, forcing them to pay bribes to Russian police officers as well as to experience fraud and deceit by employers and intermediaries. Consequently, a constant sense of insecurity associated with fear of discrimination, injustice, exploitation, abuse and illegality follows many Central Asian migrants in their everyday lives. Due to these daily insecurities and hardships, some Central Asian migrants either commit crimes or become victims of fabricated criminal charges initiated by Russian police officers who are under pressure from their superiors to produce a certain number of criminal cases every month. As a result, some Central migrants end up in Russian prisons, where they experience a new socio-legal environment with very different rules of conduct and social behavior. In the next section, drawing on my interviews with Uzbek ex-prisoners who served their sentence in Russian penal institutions, I will present some background information and statistical data about Central Asian prisoners in Russian penal institutions.

From the shadow economy to penal institutions

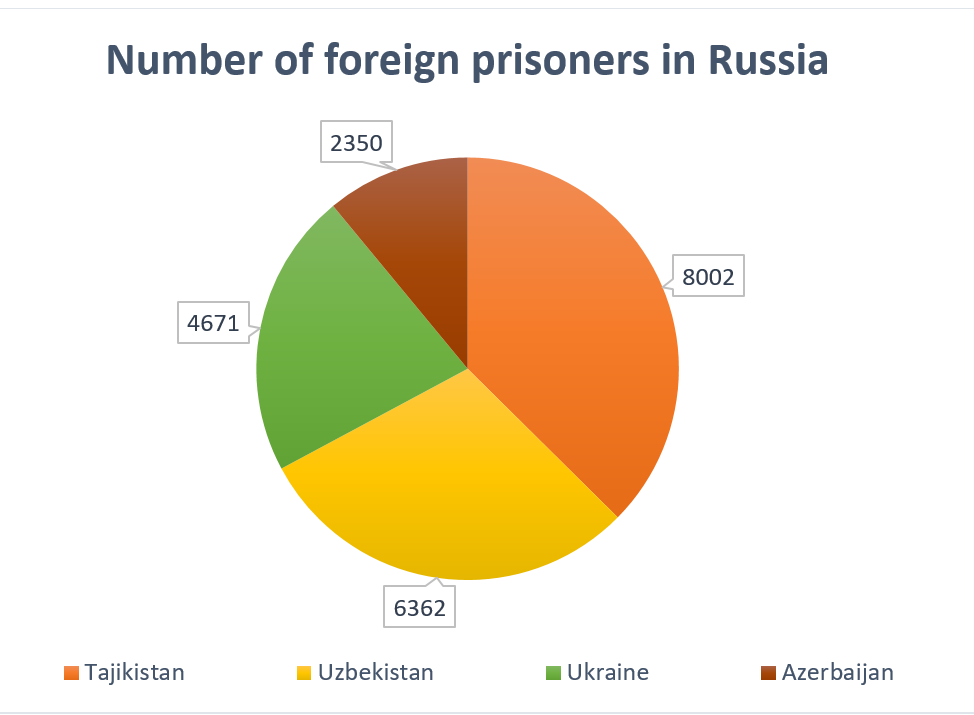

According to Russian media reports, which draw on official data from FSIN, as of 1 July 2017, 618,490 people were serving sentences in Russian prisons. Tajik migrants constitute the largest number of foreign prisoners in Russia, with 8,002 citizens of Tajikistan serving sentences in Russian prisons. Uzbek migrants occupy second place – 6,362 Uzbek citizens can be found in Russian penal institutions. Then, citizens of Ukraine (4,671 Ukrainian prisoners) and Azerbaijan (2,350 Azerbaijanis) occupy third and fourth places.

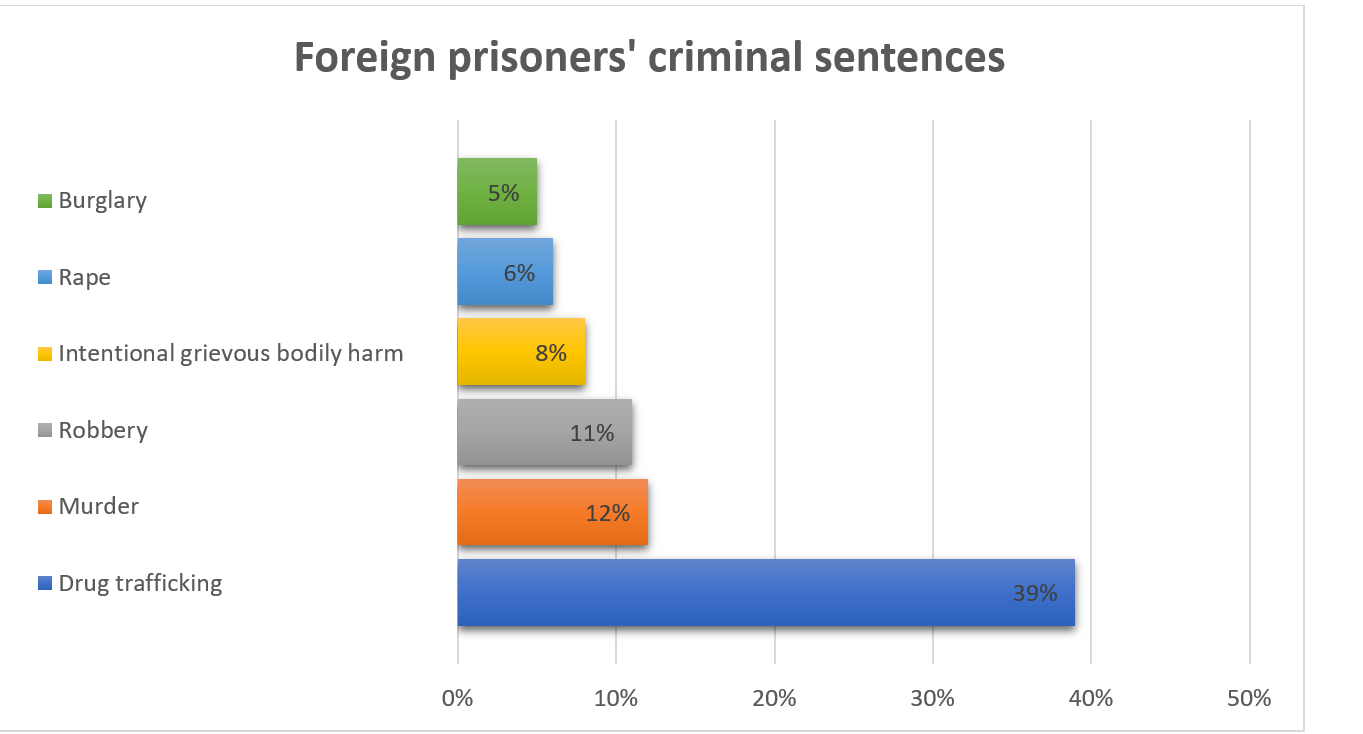

According to FSIN, more than 90% of foreign citizens end up in Russian penal institutions for committing serious crimes: 39% related to drug trafficking, murder stands at 12%, robbery 11%, intentional grievous bodily harm 8%, rape 6%, and burglary 5%.

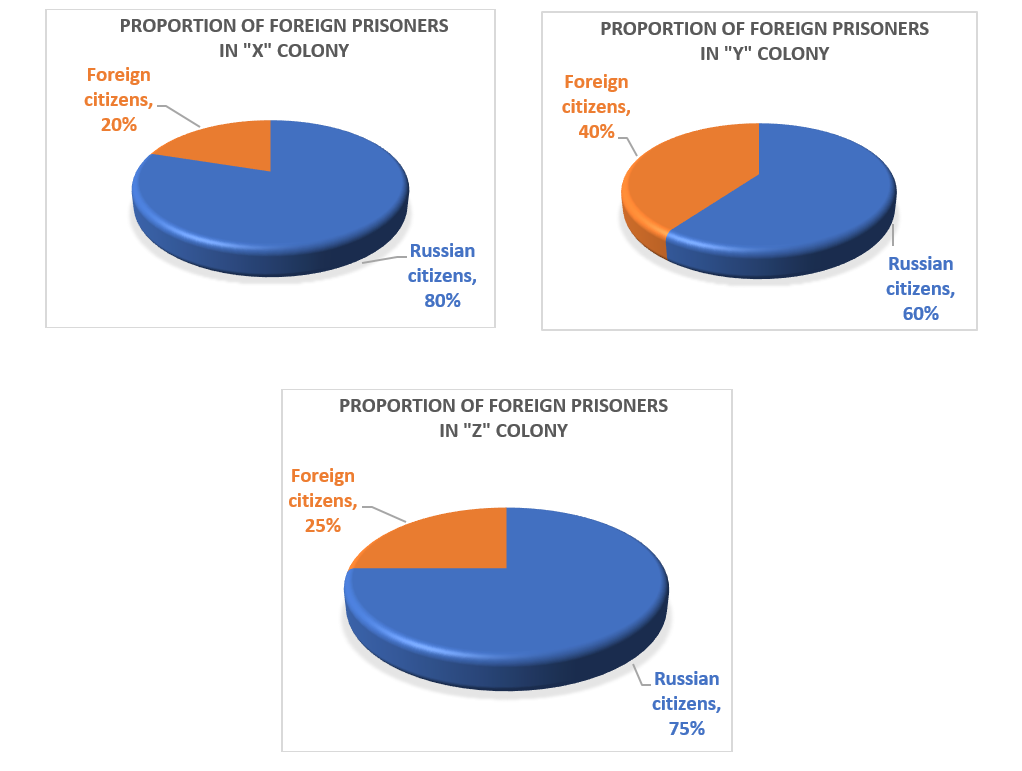

FSIN does not regularly provide data on the number of foreign (non-citizen) prisoners in Russian penal institutions. The official data presented above is rather dated, and it is very challenging to obtain up-to-date statistics on the number of foreign prisoners in Russian penal institutions. However, in the GULAGECHOES project, drawing on my interview data, I made an attempt to construct a rough overview of the ethnic and religious composition in different penal institutions. Let’s take the example of one of the correctional colonies, and let’s call it correctional colony ‘X’, in a region 500 km east of Moscow. According to our interviewee, when he served his sentence there between 2010 and 2016, there were approximately 3,000 prisoners serving their sentences alongside him, amongst which 15-20% were foreigners/non-Russian citizens. The majority of these foreign prisoners were from Central Asia (Uzbeks, Tajiks) and from the Caucasus (Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Armenians). There was also a small group of prisoners from Ukraine and Moldova. In other words, in the correctional colony, it was possible to find prisoners from all former Soviet republics, with the exception of three Baltic states. The most common criminal sentences among Central Asian migrants/prisoners were related to drug trafficking, robbery and murder.

But the ethnic composition of prisoners varies from region to region and colony to colony. At correctional colony “Y” in a neighbouring region, the situation was quite different. Our interviewee who served his sentence there reported that out of total 1450 prisoners, 40% were foreign citizens, a majority of them coming from Central Asia. There were approximately 250 Tajiks and 60 Uzbeks serving their sentence. Again, the most common crime was drug trafficking, robbery and murder. In yet another colony we will call colony “Z”, situated in a region north of Moscow, the proportion of foreign prisoners is 25%, so it stands roughly in between colonies “X” and “Y” in terms of the proportion of incarcerated foreigners. As our interviewee from this colony reported, during 2010-2015, out of total 1,300 prisoners, 325 prisoners were foreign citizens: 150 citizens of Tajikistan, 85 citizens of Uzbekistan, 60 people from Georgia, and 30 citizens of Kyrgyzstan.

All three interviewees noted that the percentage of foreigners in Russian prisons could be higher than their estimates, as they provided the accounts of foreign prisoners who were more visible and constituted the largest non-Russian ethnic group. On the whole, it is possible to suggest that the proportion of foreign citizens in Russian penal institutions ranges between 20 and 40% depending on the region, with Central Asian citizens constituting the largest group among foreign prisoners.

A large concentration of Central Asian nationals in Russian penal institutions can be explained by the absence of inter-state agreements between Russia and Central Asian republics (Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) on the transfer of prisoners. Let’s take the example of Uzbekistan. More than half the people I interviewed expressed a strong preference for serving their sentence in Uzbekistan. Some of them even sent a formal request to FSIN, the Russian Prison Service, asking for a transfer to Uzbekistan so that they can serve prison sentence in their home country. FSIN usually rejects such transfer requests, citing the absence of an inter-state agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Uzbekistan. FSIN instructs Uzbek prisoners to send their request directly to the General Prosecutor’s Office of Uzbekistan, which has the prerogative to initiate the transfer of Uzbek prisoners. On an inter-state level, there are two legal documents that focus on cooperation in the field of organizing the execution of criminal sentences: (1) The Agreement between the Government of Uzbekistan and the Government of Russian Federation on Cooperation in Combatting Crime, signed in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on July 27, 1995 and entered into force on July 27, 1995; and (2) The Minsk Convention on Legal Assistance and Legal Relations in Civil, Family and Criminal Cases (January 27, 1993). These two documents mainly discuss inter-state collaborations in the field of criminal investigations and the extradition of persons, but they do not contain any provisions on the transfer and exchange of prisoners. Given the absence of any legally-binding agreement between two countries, the General Prosecutor’s Office of Uzbekistan selectively considers applications on the transfer of prisoners from Russia to Uzbekistan, approving only those cases that are of special importance to the government or high-level state officials.

On April 23, 2016, the Russian government came up with a draft agreement (N 339) on the transfer of prisoners between the Russian Federation and Uzbekistan. The Russian Government has already expressed its willingness to sign the agreement, but so far no sympathetic gesture has come from the side of Uzbekistan. The absence of an endorsing reaction is quite understandable: if this agreement is signed by both parties, it is obvious that Uzbek authorities will receive a huge number of transfer applications from citizens of Uzbekistan currently serving their sentence in Russian prisons. Considering the fact that Uzbekistan’s prisons are already overcrowded, it is highly unlikely that the authorities of the country would be willing to sign this agreement.

Central Asian Muslim prisoners in Russian “zonas” (penal institutions)

In this section, I present some intriguing insights from my ethnographic interview which focuses on the experiences of Uzbek ex-prisoner “Farhod” (identified by a pseudonym), who served sentence at the correctional colony “X” between 2010 and 2015. The number of the correctional colony is not indicated here in order to protect the anonymity of our interviewee. By using the case of Farhod , I aim to demonstrate two things. First, I will demonstrate how traditional prison subcultures, which are notorious and widespread in Russian correctional colonies, intersect with Muslim minority prisoners. The intention is to illustrate how the emergence of Muslim subcultures and practices are shaping the traditional hierarchies and power relations in Russian penal institutions. Second, I will show how Muslim prisoners organize their daily life and routines. By describing their everyday lives, I illustrate how these daily practices and routines might have been affected by the restrictions caused by COVID-19.

Farhod (male, 37 years old) is from the Fergana Valley of Uzbekistan. He arrived in Russia in 2001 when labor migration was still a new phenomenon both in Russia and Uzbekistan. Farhod’s father owned an Uzbek restaurant in the regional capital’s wholesale bazaar which served as a main hub for Uzbek entrepreneurs (rossiychilar) who exported fruits and vegetables from Uzbekistan to Russia. Thanks to his father’s strong position in Russia, Farhod did not experience any hardships and easily integrated into the local labour market and everyday life. Farhod’s life under his father’s protection was pleasant. He helped his father in running the restaurant and earned at least 50 USD per day, an income which was more than enough to have a decent life in the city. However, Farhod’s good life changed in 2010 as a result of his drug addiction, which led to criminal charges and a prison sentence. As Farhod was dependent on drugs, he often carried hashish and sometimes heroin in his pocket so that he could use them whenever he felt the need. In March 2010, Farhod was stopped and frisked by an OMON officer (Russian paramilitary police) on the street while he was carrying drugs in his pocket. As a result, Farhod was arrested immediately and received a prison sentence of 5 years. After being held in a remand prison (a jail or pre-trial detention center) for eight months, Farhod was transferred to colony X in November 2010, and served his sentence until 2015.

In the post-Soviet space, both prisoners and ordinary people use the word “zona” to refer to prisons. Colony X is a strict regime correctional colony, or zona, for males who serve prison sentences for the first time (known in Russian as a colony for pervokhody). In the words of Farhod, Colony X was a “black zona” (черная зона), where criminal authorities and informal networks represented by people known such as “polozhenets” (положенец), “smotriashiy” (смотрящий) and “barashnik” (барашник) played decisive roles in determining “the rules of the game”, whereas formal prison management structures such as “menty” (менты – a Russian colloquial nickname for police officers), “operativniki” (оперативники) and “nachal’nik” (начальник/head of the prison) had a limited impact on regulating prisoners’ everyday life and routines. But things are different in so-called “red zonas” (красная зона). In red zonas, formal prison management structures have full control and prisoners must comply with the colony regime rules and work on a daily basis.

As Colony X was a black zona, prisoners enjoyed unimpeded mobility inside the zona and freely used mobile phones. The existence of mobile phones allowed prisoners to maintain daily contact with both their families and social networks. Cigarettes and tea served as the main currency (valyuta) in prisoners’ daily transactions and relations. Every night, prisoners played cards (qimor) and generated income for the “obshak”, a mutual assistance fund among prisoners.

Colony X was a multicultural prison. There were approximately 3,000 prisoners serving their sentences there. Russians were the dominant ethnic group in zona, along with a considerable number of Chechens, Dagestanis, Ingushs, and Tatars, as identified by my interviewee. Approximately 15-20% of prisoners were foreigners (non-Russian citizens), mainly from Central Asia (Tajiks, Uzbeks, Kyrgyzs) and the Caucasus (Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Georgians, Abkhazians). There was also a small number of prisoners from Ukraine and Moldova, as well as 4 prisoners from the Middle East who allegedly ended up in the zona due to their involvement in drug-related activities. The living or domestic zone where Farhod lived consisted of 15 barracks (dormitory blocks) that housed approximately 400 prisoners each. On average, 20-25 prisoners lived in each block. Among the 400 prisoners in Farhod’s block, at least 70 prisoners were Muslims. The polozhenets, a criminal authority who controls the zona, was also a Muslim from Chechnya.

In the words of Farhod, Colony X was a Muslim-dominated zona thanks to the Chechen polozhenets (i.e. someone high up in the local criminal hierarchy who makes some of the decisions about daily life in a zona dominated by informal criminal groups instead of the prison administration), who made sure that Muslims had more influence and voice than non-Muslims such as Russians, Ukrainians, Abkhazians and Armenians. The Chechen polozhenets also made sure that Muslims had access to halal food and could pray five times a day. Thanks to the efforts of the polozhenets, the prison administration allowed Muslim prisoners to use one of the unused barracks as a mosque so that they could pray in a large group. The imam (religious leader) was an Uzbek from Tajikistan’s Khujand region. The imam was known as “Sheykh” among prisoners due to his rich knowledge of Islam and oratory skills.

The mosque, located in another building, was open all the time for all prayers, with the exception of bomdod time (morning prayer before the sunrise). Muslims usually read namaz (pray) together, in a jamoat (gathering/in a large group setting). Friday prayers were the most attended religious event. It was possible to count at least 100 people during Friday prayers. The main role of Sheykh was to lead prayers, tell different hadith (record of the traditions or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) before the prayers and advise Muslims on how to follow the basic tenets of Islam. These daily prayers at the mosque transcended ethnic differences and created a strong solidarity among various Muslim prisoners. Regardless of their ethnic group, it was possible to see Uzbeks, Tajiks, Chechens, Dagestanis, Azerbaijanis and Tatars unified during prayers. The mosque was used not only as a gathering place for Muslims, but also served as a site of support and networking among Muslim prisoners. Especially, young and newly arrived prisoners received moral support, learned about zona rules and acquired initial adaptation skills through conversations with other Muslim prisoners.

In addition to daily prayers, Islam was also incorporated into the daily life of Muslim prisoners. As it is not allowed to eat pork in Islam, many Muslims did not eat any food at the zona’s canteen. There was no any guarantee that meals prepared at the canteen of the zona were halal. Everybody knew that cooks at the canteen used the same cooking pots for pork and beef, so Muslims did their best to avoid canteen meals. Therefore, Muslims usually gathered money and cooked separately inside their barracks. During Ramadan, many Muslims fasted together and shared morning (saharlik) and evening (iftar) meals.

Islam and prisoner hierarchies

Engaging in daily prayers and Ramadan opened many doors to Muslims. As each prayer requires a separate cleaning and purifying ritual (tahorat), special bathing and cleaning facilities were arranged in several toilets. But these facilities were only accessible for Muslims, and all other non-Muslim prisoners were not allowed to use them. This created a kind of hierarchy between Muslim and non-Muslim prisoners. Even though non-Muslim prisoners constituted the majority in the zona, Muslims occupied privileged positions and managed to better organize their daily life and religious practices. This was possible due to fact that Muslims were united and built strong solidarity based on Islamic principles, whereas there was no unifying ideology among Russians and other non-Muslim prisoners.

In fact, the influence of Muslims in the zona has increased in recent years to such an extent that many Russians have started to use Islamic and Arabic expressions such as “Assalamu Alaykum”, “Inshallah”, “Allahu Akbar” and many other words. By showing respect to Muslims, non-Muslim prisoners were able to join Muslim many parcels from the outside. Eid was celebrated in an especially fancy manner, and the traditional Uzbek meal of plov was distributed to all prisoners on Eid day, regardless of ethnic and religious belonging. The role of the Chechen polozhenets was crucial in all these processes, as he constantly lobbied and defended the interests of Muslims inside this particular zona.

Surveillance over Islam by Prison Staff

As the influence of Muslims in the zona increased, the prison administration gradually intensified their surveillance over religious practices. This surveillance focused mainly on radicalized Muslims from Dagestan, who propagated the Wahhabi and Salafist interpretation of Islam. Some religious books were banned by referring to their extremist content. The main worry of the prison administration is that other Muslim prisoners would also be affected by these radical interpretations of Islam. As a result, the prison administration began closely monitoring all religious activities. They regularly communicated with Sheykh so as to instruct him what to say during daily prayers. When entering the zona’s mosque, all Muslims went through a special passage or crossing point which was equipped with a CCTV camera in order to keep track of all practicing Muslims. For example, approximately 100 people came to Friday prayers, but only 40 of them were practicing Muslims and read namaz five times a day. So, these 40 people regularly entered mosque through this special crossing post. In addition, all Muslims knew that there was one informer among them who reported to the prison administration on what was being said and what was happening in mosque. Considering these risks, Muslims were careful and did not openly express their religious ideas. In order to keep peaceful relations with the prison administration, the Chechen polozhenets also made sure that no radical ideas were spread among Muslims. The polozhenets was aware that the prison administration might shut down the mosque if radicalized Dagestanis became active and spread their ideology. Therefore, it was in the interest of both the prison administration and Chechen polozhenets/bratva to contain radicalized Muslims.

Another aspect of Colony X was the ethnicity-driven support and solidarity networks and relations. Even though any overt expression of racism, ethnic identities or zemliachestvo (shared territorial origin) was strongly discouraged and even punished by both formal (prison administration) and informal (criminal authorities) power structures, things worked differently in practice. Daily relations, conversations and networking among prisoners was clearly based on ethnic identities. Daily conversations and arguments over historical events and facts were key instances where it was possible to see the expression of ethnic identities. Uzbeks enjoyed more prestige and respect among prisoners due to the fact that in the 1920s Uzbek Basmachi (guerrilla fighters) groups fought and resisted the Soviet Bolshevik government, while other ethnic groups such Kazakhs, Kyrgyzs and Turkmens or Tatars did not show such strong resistance to the Soviet regime.

The use of Tamerlan as a founding father of the contemporary Uzbek state was also very common among Uzbek prisoners. Uzbeks were seen as a fearless and rebellious nation in the prison. This was frequently mentioned by the Chechen polozhenets and the smotryashye, who occupied the highest positions in informal power hierarchies in the zona. On the other hand, according to my interviewee, Tajik prisoners proclaimed that they were very proud of their intellectual contribution to human civilization, and often claimed that great scholars of the Islamic Golden Age such as Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Al-Khwarizmi were Tajik/Persian and invaded the world with pen, while “barbaric Turkic groups” (with which they associated Uzbeks, Kyrgyzs, Kazakhs, Tatars, Azerbaijanis, according to my interviewee) came from the Urals and Siberia and colonized the Central Asia, a region that was originally inhabited by Persian-speaking groups. Tajiks, as Farhod said, also claimed that Samarkand and Bukhara were originally Tajik cities which have nothing to do with contemporary Uzbekistan. Farhod recalled that Georgian prisoners also used historical facts and referred to Stalin’s Georgian ethnicity when talking about their historical influence. Georgians often claimed that the origin of Gulag and the street world is closely connected to Stalin and that authentic “thieves in law” (vory), which is an important category for prison subculture and informal criminal hierarchies in prisons, originate from Georgia.

My interviewee described a situation in which each ethnic group in the zona tries to take care of their members. Farhod provided some examples of mutual assistance activities among Uzbek prisoners. For example, if a new prisoner who is from Uzbekistan arrives in the zona and is placed in quarantine (the first point of arrival, a place of adaptation for the first weeks), at least one member from the Uzbek prisoner community visits him in order to check if he is a “decent person” (poryadochniy muzhik), and, if deemed to be so, whether he needs any basic items such as food, tea, a pack of cigarettes, cleaning items (soap, a dental kit). Uzbeks also explain the basic rules of zona life and the local informal rules, known as vorovskoy zakon (“thieves’ law”) in order to make sure that their new member behaves properly. Taking care of zemlyaks (people from the same region as you) is a question of honor and reputation among prisoners. If one Uzbek is suffering and other Uzbeks do not help him, prisoners from other ethnicities mock and laugh at Uzbeks, a thing that creates an intra-group solidarity and forces Uzbeks to take care of one another, as Farhod recounted through his own interpretation of prison dynamics. Uzbeks also had a a joint korobka (box, mutual fund) and each Uzbek contributed what they have to the korobka. If someone received a parcel in the mail (e.g. tea, cigarettes, fruits, bread, canned meat, etc.) from family, friends or other close people, it was the norm among Uzbeks to give part of their parcel to the korobka. Other Uzbeks who did not receive any parcels usually worked inside the zona and made contributions to the mutual fund once a month when they received their salary. There was thus an unwritten law among Uzbeks that one must share whatever he has with their zemlyaks. The main aim of having a korobka was to maintain a social safety net among Uzbeks so that they looked united and ketp their “dignity and honor”, as Farhod recounted. This mutual aid practice is comparable to typical mahalla (community) based social safety and risk-stretching practices that are part and parcel of everyday life in Uzbekistan. In other words, Uzbek prisoners reproduced and maintained their mahalla-type mutual assistance practices in the prison context.

Such ethnicity-driven mutual aid practices also existed among other prisoners. Other tight-knit ethnic groups in the zona, for example, Tajiks, Chechens and Dagestanis also had a similar mutual assistance funds. But such ethnicity-driven practices were not strong among other ethnic groups. Even though Russians were a majority group in the zona, they were weakly organized and did not have any ethnically-bound community, according to Farhod.

All in all, the aforementioned ethnicity and religion-driven norms co-exist with the vorovskoy zakon and with colony regime rules. While it has been typical for prisoners and those who study prisons to juxtapose the informal criminal group power over zona rules (embodied in “thieve’s law” or vorovskoy zakon) with the rule of the prison staff over all local practices, it seems it is no longer useful to appeal to such a dichotomy in Russian penal institutions. Rather, parallel prison subcultures based on ethnic and religious identities seem to be gradually emerging. This means that Russian penal institutions are becoming more legally and culturally plural due to large-scale migration and incarceration of migrants, which shapes societal transformations in Russian society both outside and inside zonas.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on Muslim prisoners from Central Asia

The idea of writing this blog was partly driven by the fascinating stories of “Botir” (identified here by his pseudonym), an Uzbek ex-prisoner whom I interviewed in February 2020 and with whom I speak once a week through Telegram Messenger (a social media app). Even though he was released from a Russian correctional colony last year, he still maintains regular contact with his former barrack-mates over social media, which allowed him to stay abreast of the developments in Russian colonies. Some empirical examples and reflections provided below is thus based on my weekly conversations with Botir.

As Botir explained, lockdown measures and visitation restrictions are frequently imposed in Russian penal institutions. The correctional colonies might be closed even during the flu season, so it is not in any way surprising that FSIN decided to impose strict lockdown during the COVID-19 period. These special lockdown rules and visitation restrictions not only apply to prisoners, but also to prison officials. During epidemic times, a certain number of prison officials are usually selected to live in prison buildings, and they work without any shifts until the epidemic is over. These restrictions even apply to those prisoners whose sentence is finished and who is supposed to be released. They also have to stay in the colony and wait for their release until the end of pandemic. In other words, all contact with the outside world is stopped during the epidemic/pandemic period. Due to these severe measures, as Botir explains, the risk of infection inside zonas is very low.

The correctional colony in Siberia where Botir served his sentence is currently locked away from the outside world. Botir was also informed about the situation in other colonies due to his extensive networks with Uzbek prisoners serving their sentences in different parts of Russia. According to Botir, the situation in many other colonies is similar, which allows us to conclude that FSIN imposed similar restrictions throughout Russian penal institutions. When I asked Botir to comment on how these lockdown measures have affected Muslim prisoners, he provided the following account, which I recount below.

First, prisoner mobility inside colonies are restricted. As a result, inter-block communication has been stopped and prisoners cannot visit other blocks. This strategy may prevent the spread of virus but it may also affect the welfare of prisoners in the sense that ethnicity-driven mutual aid practices are limited.

Second, mosques in correctional colonies are closed in order to prevent the spread of coronavirus. As a result, Muslim prisoners are not able to organize around religious lines, which has implications for the power geometry in colonies. Daily jamoat (group) praying produces strong solidarity, support and networking among various Muslim prisoners, regardless of ethnic differences, as I described above. This implies that Muslim prisoners may have lost their influence and became weakly organized minority due to the COVID restrictions.

Third, Muslims’ ability to receive halal meat and products are restricted during the lockdown times. This means Muslims have no any possibility to cook their own food in barracks, as they cannot receive products from outside. This leaves Muslims in a vulnerable situation, as they have two options: either to eat at the prison canteen, where the cooking pot is used for preparing both pork and non-pork meals, or to limit their diet to bread until the pandemic is over. The latter option is more widespread among practicing Muslim prisoners.

Fourth, lockdown measures stopped the “normal” flow of information, money, drugs, and electronic devices to colonies, which is something that dramatically affects the health, welfare and psychological wellbeing of all prisoners. The quality of prisoners’ life in Russian penal institutions highly depends on the maintenance of daily communication and exchange with the street/outside world, so it is quite obvious that prisoners are heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

All in all, insights provided in this short blog post are based on interviews with limited number of informants. Due to lack of information from Russia’s prison officials, we do not have a complete picture of how many prisoners have been affected by the virus and how the COVID-19 restrictions have affected the health, welfare and psychological conditions of incarcerated people. These are some of the key questions that will be further explored in my forthcoming fieldwork, when I hopefully return to Uzbekistan in early July 2020.

To be continued in future posts and academic articles.