BY DR. OLGA ZEVELEVA

In a new article in Riddle, an online journal on Russian affairs, Dr. Olga Zeveleva analyses the state of Russian prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic and compares it to prisons in other European countries. The publication is available in Russian and in English, and is partly reproduced on the project blog.

In early August, the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service announced that during the pandemic, 3526 prison officers and 1224 prisoners had contracted the coronavirus. Human rights activists suspect that the numbers of cases may be much higher. Moreover, the threat of the virus has not yet passed. A hangover of problems that arrived with the pandemic will have now long-term consequences for prisons and prisoners.

In the sections below, I consider some of these consequences, and situate the Russian case in a global context[1] of prison policy and prisoners’ lives during the COVID-19 crisis.

Russia’s Federal Penitentiary Service says that staff who work with prisoners who have contracted coronavirus in Moscow’s jails wear special protective gear

Calls for amnesty

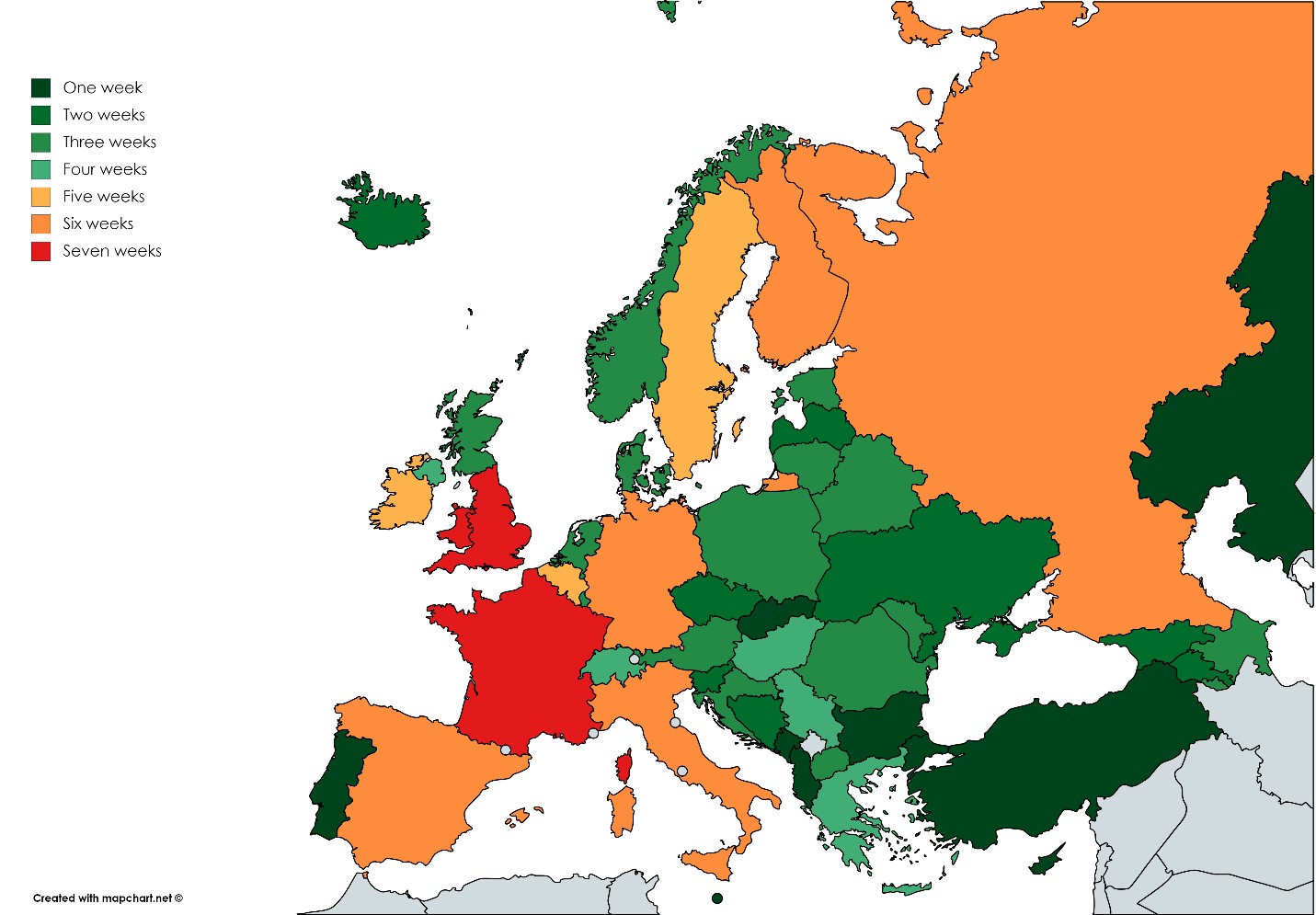

At the start of the pandemic, human rights activists and prison abolitionists called for mass de-carceration, and encouraged the public and policy-makers to fundamentally rethink whether prison is a necessary or safe form of punishment today. Some form of amnesty or early release was granted to prisoners in at least 25 countries around the world, including Portugal, the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Albania, Turkey, Belarus, and Azerbaijan (see map below). But Russia has not joined this group of nations.

In early April, many prominent Russian human rights defenders, experts, journalists, writers, directors, actors, and musicians wrote an open letter to President Vladimir Putin, calling for an amnesty that would release tens of thousands of prisoners from Russia’s cramped jails. The letter began like this:

‘Today, we are able to choose how and with whom we will take cover to save ourselves from the fatal illness caused by a virus – of course, within the limits prescribed by the authorities and doctors. But nearly 100 thousand people are deprived of the opportunity [to make such choices]. These are the people who have found themselves in jail. They are suspected of crimes, but they have not yet proven guilty.’

The proposal focused on those awaiting trial in remand facilities, but over 400 thousand additional prisoners are serving sentences in Russia’s prisons, and also facing grave danger as COVID-19 continues to spread. Not only does Russia have the largest prison population of Europe, it also has the highest rate of incarceration on the continent (i.e. 347 prisoners per 100,000 people).

Civil society’s cries for the release of prisoners were not met with enthusiasm from authorities. In fact, even the expected 2020 Victory Day amnesty was cancelled, even though it has taken place every five years for the past two and a half decades as part of a commemoration of the USSR’s victory over Nazi Germany. In spite of an overarching trend of significant reduction in Russia’s prison population over the last half decade, the Russian government has failed to take the opportunity provided by both COVID-19 and the Victory Day anniversary to offload its jails this year, and many people who could have expected to be included in the 2020 amnesty will now remain in prison. It is unclear why officials have not taken this route.

Image 1: Countries that have implemented early releases or pardons

Regime of isolation

Instead of de-carceration, Russia opted for isolating its prison population. Since mid-March prisoners have been unable to receive visits from their family members and friends. This was far from a unique strategy. Even countries that carried out amnesties also implemented prison lockdowns to fight the virus, mostly in the form of visitation bans (see map below). All Council of Europe member states banned visits to their prisons at some point in the spring of 2020.

Image 2: Number of weeks it took for each country to limit visits to prisons after the first case of COVID-19 was detected on its territory

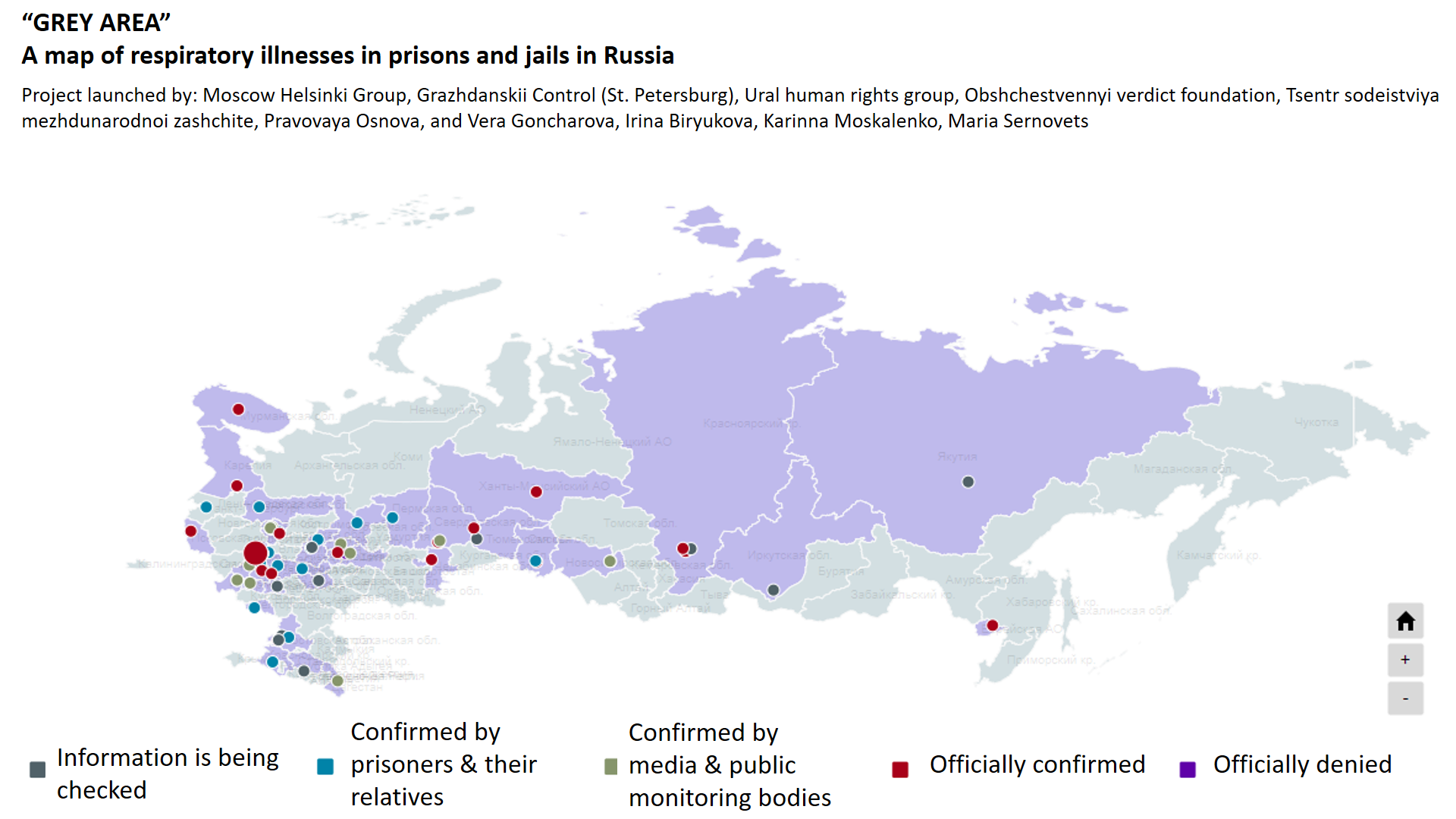

Despite calls from international organizations, including the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, for governments to carefully consider how they implement restrictions in prisons, Russia did not introduce compensatory measures. Instead, the Russian prison services implemented what some human rights defenders call a total “information blockade,” where specific coronavirus prevention policies have not been made public, leaving both prisoners and their family members guessing what the penitentiary service may do next, and when (for a discussion of historical legacies of secrecy in the Russian prison system, see this blog post by Mikhail Nakonechnyi). To counteract this dire lack of official information, a group of NGOs and lawyers launched a project called “Grey area” (Seraya zona) that monitors reports on coronavirus across the country’s prisons, mapping both responses from authorities and reports from prisoners and their families, as well as eyewitness accounts from journalists and public monitoring bodies.

In this way, common policies adopted around the world turned particularly harsh in the case of Russia. By contrast, the vast majority of other Council of Europe member states introduced some form of compensation to prisoners, most often through extending phone calls or introducing videoconferencing. Many prison systems used the pandemic to speed up digitization programmes that were already underway. Denmark even introduced video game consoles in its prisons, and allowed video calls to family members from prisoners’ own cell phones. In the UK, 900 cell phones were given out to prisoners who did not already have their own. In addition to lack of compensatory measures and transparency, several particular characteristics of the Russian prison system shaped the experiences of prisoners during the pandemic.

Though the pandemic has brought about increased isolation of almost all prisoners worldwide from their families due to visitation bans, in Russia isolation from family takes on extreme forms even in non-pandemic times due to Russia’s penal geography. Russian prisons are often located in far-flung rural areas, and prisoners are typically sent thousands of kilometers from their homes to serve their sentences. At the start of the pandemic, as travel plans of people all around the world began to topple, some families had already made the expensive trek across the country to see their loved ones, only to be refused entry to visitation quarters of the prison upon arrival. Public monitoring bodies and lawyers also found themselves facing new hurdles when traveling to and trying to enter prisons from March 18 onwards, which prevented prisoners from accessing legal help and diminished the chances for continued public oversight over penal institutions during the pandemic. Problems of access were not uniform across Russia, and varied depending on decisions made locally.

In some regions and in some prisons, the delivery of parcels to prisoners was halted or severely disrupted. Among those affected by this problem were particularly vulnerable groups who have trouble with food in the prison canteens, including people who require special diets due to illness, and people with dietary restrictions for religious reasons (for example, Muslim prisoners who require halal food. For a detailed discussion of the issues faced by Muslim prisoners, see Rustamjon Urinboyev’s blog post). Some prisoners are also accustomed to receiving basic or complex medication in parcels delivered by family members or charities and NGOs, which was also hampered during the pandemic. The longer-term negative effects of such restrictions on the health and wellbeing of already weakened prisoners are yet to be assessed.

Riots, secrecy, abuse

The theme of dissatisfaction among prisoners mentioned in the opening quote to this post has also emerged across prison populations globally. Between mid-March and mid-April alone, prison riots broke out across 36 countries. In 15 of these countries, they resulted in death. Over 100 people died in these riots, and with very few exceptions these were prisoners, not prison guards. Prisoners rioted to demand extra protection from the virus, increased sanitary measures, and early release.

In Russia, we know of one riot and one death that resulted from it in a penal colony in the Siberian town of Angarsk in early April. According to Alexei Fedyarov, who works for prison NGO Rus Sidyashchaya, it does not seem that this riot was related to the virus, and was most likely caused by a power struggle between the prison administration and prisoners. Even so, the pandemic situation may have been a contributory factor that led the daily struggle between prison guards and prisoners to boil over. According to available reports, the unrest started with prison guards beating up a prisoner, and about twenty prisoners slashed their wrists in protest. In the violence that followed, about 300 prisoners were injured and one person died. In May, human rights defenders learned of a second death that took place following the riot, from injuries sustained during the violence (this has been denied by prison authorities). Several buildings on the premises of the penal colony burned down.

This major event terrified the families of those held in the Angarsk prison, and shook the human rights community, not least because the lockdowns prevented them from accessing the prison and protecting those involved in the unrest. Though the riot was not directly caused by the virus, it lay bare some ways in which the Russian prison system is coping with the pandemic.

First, lockdowns are psychologically taxing for prisoners, and in a context of limited information and reduced contact with the outside world, relationships between prisoners and the prison administration become ever more strained. This is exacerbated by the pandemic regulation adopted in Russia that stipulates that prison guards must work in 14-day shifts, living in the prisons for two weeks at a time (for a discussion of what it is like for prison guards to live in prison, see Costanza Curro’s blog post).

Second, human rights workers and public monitoring committees were initially unable to access the site of the riot and obtain in-person accounts from prisoners who saw events unfold, nor were they able to offer swift legal protection due to limited access to the prisoners. This was in part due to the fact that hundreds of prisoners were transferred out of the facility immediately following the riot, and human rights workers and their families had a difficult time tracking them down due to lack of information about where they were being taken.

Third, while human rights workers were struggling to access those involved in the riot, authorities were questioning these prisoners, and there is evidence of grave physical abuse of one of the men blamed by the prison services for starting the protest, Khumaid Khaidayev. When Khaidayev’s lawyers finally saw him several days after the riot, he was bruised, his face was disfigured, and his fingers and toes were broken. Khaidayev’s brother fears that widespread anti-Chechen attitudes among some of Russia’s law enforcement officers means he is at even greater risk of physical abuse and faces a serious sentence. The lockdowns have made it very difficult to ensure due process and to protect the prisoners from human rights violations. Moreover, Justice Minister Konstantin Chuychenko went as far as to claim that the riot was organized by “forces from the outside”, namely human rights defenders.

The way in which the reverberations of the riot played out illustrates the selectiveness of isolation in Russian prisons during the pandemic, and demonstrates the antipathy of government officials and prison service towards human rights defenders. While prosecutors have had access to prisoners throughout this time and court hearings have been allowed to proceed via WhatsApp, lawyers and public monitoring bodies have faced significant hurdles when attempting to meet with prisoners, and they even have failed to obtain video calling rights.

Continued links to the outside world: informal practices, exceptions, and a mobile prison population

One can hardly analyse how life unfolds inside a Russian prison during a pandemic without considering informal links to the outside world, prisoner hierarchies and subcultures, and the power of prison gangs. In prisons where informal hierarchies and gangs exercise relatively more power (these are known colloquially as “black” prisons, as opposed to “red” prisons where the administration has full control over the prison regime), the isolation regime is constantly negotiated and re-negotiated between the prisoners and the administration. Connection to the outside world is upheld through vast informal networks using cell phones smuggled into the prison. Prisoners stay connected to prisoners in other penal colonies, other regions, and with “the street.” While some countries announced that prisoners could officially start using cell phones to communicate with family during the lockdown, in Russia many prisoners have access to cell phones despite the official ban on them.

While the coronavirus lockdowns have sometimes made it more difficult to maintain connections between prison and “the street”, these links have not been severed entirely, with significant variation from prison to prison. As Yura wrote on Telegram on 17 May:

‘The only thing that’s cheered up the prisoners lately is the delivery of brand new, unopened boxes of cigarettes to the camp’s obshchyak [informal common fund] last night. This, I believe, is the perfect illustration of the current isolation regime – it’s all window dressing. Official parcels? Don’t even think about it, the virus can enter prison walls that way. But allowing obshchyak cigarettes through? Be my guest! Do you think they disinfected the boxes with soap water or something?’

But prison walls remained porous even through official channels. Despite the announcement on March 18 that a ban on prison visits was in place throughout Russia, that same day a news post on the website of a prison administration in Yekaterinburg congratulated newlyweds on a wedding that took place within prison walls.

A prison wedding, 18 March 2020

The next day, a delegation of Orthodox priests arrived at another prison in Sverdlovsk region to meet with prisoners and visit the church and library. This shows how permeable prisons remained to outside visitors, even when families and friends of prisoners were no longer allowed in. The events also attest to the vast variation of on-the-ground practices across the complex landscape of Russian penal institutions.

An Orthodox Christian priest pays a visit to a prison, 19 March 2020

Numerous worrying reports from prisoners, posted on social media platforms and passed on to NGOs and journalists, describe extremely uneven implementation of COVID-19 rules in prisons. While the Federal Penitentiary Service insists that protective measures are in place, such as mandatory mask-wearing for guards and disinfection of prison premises, there are also reports of prison guards failing to wear masks, personnel ignoring prisoners with flu-like symptoms, and failures to isolate such prisoners. According to Yura’s Telegram notes from prison, in early April, 2.5 weeks after the prison services announced the introduction of special measures to stop the spread of infection, prison guards were still causing anxiety among prisoners fearful of the virus:

‘…Measures for the prevention of infection inside the penal colony are nowhere to be seen: there’s been no disinfection or cleaning of the premises, and staff don’t have full kits of personal protection gear. By personal protection gear I mean surgical masks which don’t meet the requirements of respirator masks, and gloves, which I saw only one staff member wearing. Starting Monday, staff began wearing “muzzles” during inspections on the barrack square. And even so, almost half of them wear the masks on their chins or don’t use them to cover their noses. “It’s uncomfortable,’ one of them says.’

Mobility of prisoners and recently released prisoners also continued throughout the country. Prisoners could still be transferred from one institution to another during the pandemic, potentially spreading the virus or contracting it along the way. Moreover, prisoners released during the pandemic faced a daunting new reality of lockdowns, limited transportation opportunities, and very few possibilities to find housing, begin work, and set up their daily lives post-release.

Conclusions

We are yet to learn about the numbers of prisoners and prison staff affected by the virus, and whether death rates have spiked among prisoners over the course of this period. But health effects beyond infection and death rates must also be taken into account. Many prisoners have found themselves cut off from private supplies of food and medication over the past four months, which could have a long-term impact on their wellbeing. There are reports that prison medical departments, already suffering from a lack of qualified medical staff, have buckled under the weight of scared patients, overworked doctors, and sporadic deliveries of supplies. These departments are often unable to meet the medical needs of prisoners under normal circumstances, and they have struggled even more in the face of the pandemic, leaving prisoners vulnerable to illnesses and health problems other than COVID-19.

Psychological effects of the lockdowns cannot be underestimated. It is widely documented that the lack of opportunity to see family and friends has grave consequences for prisoners’ mental health. The chaotic manner in which the Federal Penitentiary Services has communicated COVID-19 policies to prisoners and their families has made their daily lives unpredictable and volatile. Families of prisoners who have been transferred between institutions over the course of the pandemic have often lost touch with their loved ones for weeks, leaving family members to suspect the worst.

Human rights defenders, while rallying behind an amnesty bill and scrambling to access information about their defendants, have been dismissed by the Minister of Justice as a group that is trying to use the media to unsettle the situation in prisons. The Federal Penitentiary Services issues regular statements denouncing media reports on problems in the prison system and coronavirus cases as “fake news” and slander.

Finally, challenges prisoners face upon release have become ever more salient in light of the COVID-19 crisis. In addition to the logistical issues of traveling home or even finding a home, ex-prisoners must grapple with finding employment in a struggling economy and accessing state services amid lockdowns and quarantines. The dearth of organizations and government programmes that help in matters of adaptation after release means that many people find themselves in very difficult situations upon leaving prison.

While many of these problems plague penal systems worldwide, the lack of communication and transparency on the part of Russia’s prison authorities, prisoners’ reliance on support from family for food, medicine, and other basic supplies, and the government’s suspicion towards human rights workers have exacerbated the impact of the pandemic in Russia. We are yet to learn more about how prisoners’ lives have been affected by the policies of the past four months.

[1] The global context provided in this blog post is based on recent research that is discussed at length in the manuscript titled “COVID-19 and the prisons of Europe: Policy convergence in pandemic times?” by Jose Ignacio Nazif-Muñoz and Olga Zeveleva, currently in submission to The Lancet.

Please see the original version of this post in Russian and in English on Riddle.