BY PROFESSOR JUDITH PALLOT AND DR. BRENDAN HUMPHREYS

In this new blog post we discuss what the future might hold for captured combatants in Ukraine and protesters against the War in Russia.

Shorter versions of this post are published in Riddle and The Guardian newspaper.

On 15th March Sergey Lavrov wrote to the General Secretary of the Council of Europe withdrawing Russia from the Council of Europe. This is a case of jumping before it was pushed, because Strasbourg was scheduled on 14-15th March to discuss the full expulsion of Russia. The General Secretary of the Council, Marija Pejcinovic Buric, had warned in an interview with AFP that unless Russia immediately and unconditionally ceases hostilities “the Committee of Ministers and the Parliamentary Assembly (of the Council of Europe, PACE) will move forward, in the direction of an expulsion.” [i] The expulsion of a member state of the COE is unprecedented in the history of the Council of Europe.[ii]

The exit of Russia will leave people seized on the battlefield or arrested for protesting the war, without the protection of appeal to the ECHR for violations of their human rights. It also means that Russia could take the opportunity, recommended by Dmitry Medevedev, to re-activate the death penalty. Effectively, it removes the last restraint on how Russia treats the people it detains for real or imagined offences. Meanwhile, as Russia name the war it is prosecuting in Ukraine for what it is, it will not feel itself bound by the Geneva Convention in its treament of soldiers and citizen seized on the battlefield, whether professional soldiers or ordinary citizens defending their country. In a recent twist are the reports on 20th March of alleged force relocation of Mariupol inhabitants to Russia.

One respected Russian historian recently gave a prognosis of the worst-case scenario for human rights in Russia which included “mass repression and concentration camps”.

The leaked letter of American UN Ambassador Crocker to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, discussed on social media gave chilling details of the consequences of the war in Ukraine based on previous Russian operations. We should expect:

“ … targeted killings, kidnappings/forced disappearances, unjust detentions, and the use of torture, [that] would likely target those who oppose Russian actions, including Russian and Belarusian dissidents in exile in Ukraine, journalists and anti-corruption activists, and vulnerable populations such as religious and ethnic minorities and LGBTQI+ persons. Specifically, we have credible information that indicates Russian forces are creating lists of identified Ukrainians to be killed or sent to camps following a military occupation.”

In this blog, on our research on the breakup of Yugoslavia and on the Russian prison system, we speculate what awaits people seized in occupied Ukraine or who protest the war whether on the streets of Russian or captured Ukrainian cities. The people at risk are soldiers (who as far as Russia is concerned are not prisoners of war and, therefore, unprotected by the Geneva Convention), armed volunteers, future partisans, civilian oppositionists, and anyone anywhere who resists or protests the Russian occupation.

The Familiar Playbook

We can rely on what has been happening since the annexation of Crimea to predict the fate of the people seized and detained in new territories occupied by the Russian armed forces. We leave on one side the possibility, we note above, of the reintroduction of the death penalty in Russia and reports emanating from the breakaway territories in Eastern Ukraine over the past 14 years of summary executions, kidnappings, torture, and rape.

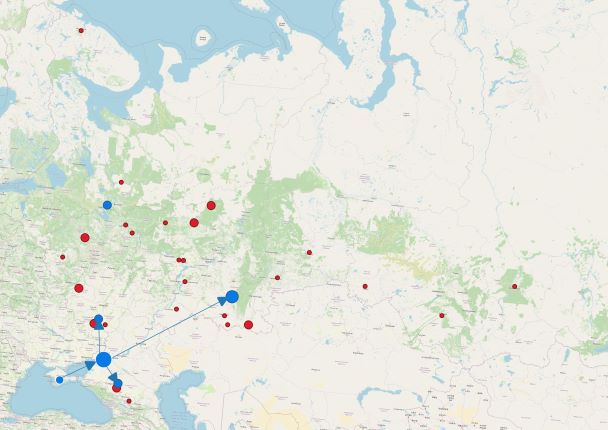

In Crimea, the main target in the resident population has been Crimean Tatars, who, for example by not taking part in elections, have passively resisted Russian rule in Crimea since 2014 – and witness the heroic protesters taking to the streets of Kherson against Russian occupation. As Muslims, the Crimean Tatars have been particularly vulnerable to accusations of belonging of radical Islamic groups, such as Hizb ut-Tahrir, which is banned in Russia.[iii] Many Crimean Tatars in prison are on Memorial Society’s list of political prisoners. The map below, constructed from the Memorial list, shows, that the people accused are typically transported out of Crimea to remand prisons in Rostov oblast. Rostov has six SIZOs (Investigatory Isolators) one of which is a prison of ‘central subordination’ (FKU SIZO-4 FSIN). This SIZO is reserved for high-profile offenders considered of greatest threat to the country’s security. People detained in this prison are under FSB investigation, are kept in extreme isolation and can languish for many years before their case comes to court.

The Crimean Tatars arrested in Crimea are tried in the Southern Military District court and once convicted, are moved further into the Russian interior to serve their sentences. There, far from their homeland, they join Muslim political prisoners from the North Caucasus and, elsewhere in Russia who are similarly convicted of belonging to terrorist and extremist organisations.

Map of the distribution of Muslim Political Prisoners in Russia with Crimean Tatar prisoners arrested in occupied Crimea shown in blue.

(Map constructed by Sofia Gavrilova)

It is not only Crimean Tartars from Ukraine who have been imprisoned in Russia in the past eight years. There have been notorious cases of Ukrainian nationals and residents of the occupied territories who have, similarly, been seized and transferred to prisons in Russia. The fate of the film director, Oleg Sentsov is particularly instructive. It shows the lengths to which the Russian authorities go to use the Russian prison system to break those who oppose its military ventures, while simultaneously keeping them out of reach of the foreign press and human rights monitors. This, no doubt, is what awaits those surviving members of the Ukrainian government who may be captured and subjected to a show trial.

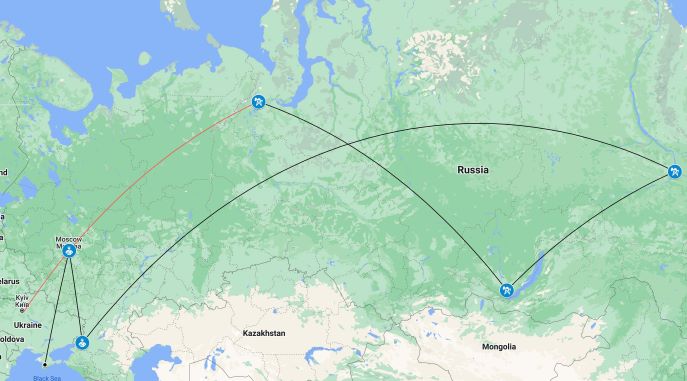

Sentsov was subjected to a 21st century version of the ‘terrors of transportation’ that had been meted out to generations of convicts by the colonial powers. In an extraordinary ‘carceral journey’, after his arrest in Simferopol, Sentsov was transported to Lefortovo (the most famous of the FSB run SIZOs of central subordination), then back south to Rostov-na-Donu to be tried, and thence, via Yakutsk and the notorious torture conveyor in Irkutsk oblast, to Labynangi in the Yamalo-Nennets AO in the Arctic circle to serve his sentence. He eventually was returned to Ukraine in a prisoner exchange, where he is now in the Ukrainian armed forces.[iv] The round trip was 19,225.9 kilometres, longer than the convict journey to Tasmania, British criminals endured in the 19th century.

Oleg Sentsov’s carceral journey

(Map constructed by Sofia Gavrilova)

All of this goes to prove, what we already know, that the much-vaunted provision in the Russia criminal correctional code for prisoners to be incarcerated in their home region or, if there are no suitable facilities, in the nearest closest region, does not apply to Ukrainian nationals who object to Russia’s seizure of Ukrainian territory.

Russian protesters

On the evidence of the past eight years, the same exception will apply to the brave citizens, numbering in the thousands, of Russia who having been taking to the streets to protest the war. They are taken off to detention centres, in over-crowded avtozaks, where they can be held for to up to 15 days. Those against whom criminal charges are initiated face prolonged periods in overcrowded pre-trial prisons. Eventually, they will come to trial, be found guilty and then be sent off to some remote corner of Russia to serve a long sentence.

All of this comes after the sustained escalation of punishments for people exercising their right under the ECHR to freedom of speech and assembly, and the obscene use of articles on ‘extremism’ and ‘terrorism’ in the criminal code to discriminate against whole groups of people on grounds of their religion, ethnicity, and political beliefs. The most recent manifestation is the law rushed onto the statute books to punish citizens spreading fake news about the military with custodial sentences of 3.5 – 15 years. For less serious offences, the state has re-introduced the ‘milder’ punishment of forced labour, bizarrely presented as an example of the humanization of punishment in Russia (see a previous gulagechoes blog of 19.8.2021 for a discussion of this “new” punishment).

It is important to remember that the custodial sentences handed to some of the thousands of protesters against the war will not be served in typical western-style cellular prisons, but in correctional colonies. These have barrack-like accommodation blocks that were originally introduced to manage the mobilization of the labour of the millions who passed through Stalin’s gulag. Despite strong criticism by the COE’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture of communal dormitories, the Russian Prison Service has clung determinedly to the principle of collectivism in penal management. And the offenders given forced labour sentences, will have to spend their nights in the self-same type of dormitories as their incarcerated fellows, under the watchful eye of FSIN inspectorate.

Will there be enough places?

The prospect as the war producing large numbers of captives in occupied territories and detainees in the Russian homeland, raises the question of whether there are sufficient spaces for them in existing carceral facilities. As we know from the Stalin era in the USSR, the infrastructure for mass repression needs planning.

In recent years, Russia has boasted of a sharp reduction in the number of prisoners in the country, presenting this as more evidence of the humanization of punishment (which is, of course, a myth, but that is another conversation) [v]. Today, c. 380,000 people are serving sentences in different categories of correctional colony with another c.100,000 in pre-trial facilities SIZOs. The overall figure for the total number of prisoners in FSIN facilities is more than half it was twenty years ago when prisoner numbers topped one million.

However, the intriguing fact is that the number of prison facilities (prisons, sizos, correctional colonies) has not correspondingly halved. Since 2019, ninety correctional colonies and remand prisons since 2019, but these closures have made only small inroads into the overall capacity of 873 facilities that remain. This means that there are plenty of places for Russian and Ukrainian citizens who are charged and found guilty under one of the now abundant articles of the criminal code punishing people for unpatriotic and oppositional activity, extremism, and terrorism.

As an example of the space capacity available in the penal estate is correctional colony no. 9 in Krasnodar krai (FKU IK-9 UFSIN po KK), which is just over 100 kilometers as the crow flies, from Mariupol in Ukraine currently being flattened by Russian missiles. According to official figures, confirmed by the office of the Prosecutor-General, the colony had 794 prisoners at the beginning of this year. This is well below the official capacity of 1202. Analogous figures for other colonies, suggest that under-fulfillment of capacity by between 20 and 33 % is the norm. Multiply this across the 643 correctional colonies in the country, and it is obvious that Russia already has capacity for tens of thousands of convicted prisoners. In fact, official figures, record that facilities for convicted prisoners are currently only 66% full. Clearly, Russia already has capacity for tens of thousands of convicted prisoners. According to my calculations the prison estate currently has somewhere around 3-400,000 spare places.[vi] And, more if they decide not to stick to the legal norm of providing 2m2 space per prisoner in correctional colonies and 4m2 in SIZOs. Once Russia has left the Council of Europe, there is no obstacles to cramming more people in, as the need arises.

It is inconceivable to me that Putin’s monstrous plan to rebuild the Empire did not factor in the need to reserve sufficient space to accommodate the next generation of political prisoners in the country’s penal institutions. The spare capacity, in other words, is unlikely to be just a fortuitous coincidence for the authorities. Furthermore, we know from recent history that the penal system has plenty of recent practice in administering maximum pain on its victims.

Will there be camps?

The experience of the Bosnian war 1992-1995 indicates what might be expected in Ukraine if the war is prolonged. Hundreds of camps were set up during the Bosnian war. Some 600 are confirmed, but Natasa Kandic – who is involved in RECOM, a transitional justice NGO – puts the number nearer 1,500.[vii] These served different purposes; to incarcerate combatants, as staging areas for massive deportations of target ethnic groups, places for torture, killings, and of brutal interrogations. A variety of different sites were used – old military complexes, schools, factories, or purpose-built facilities. Typically, the detainees were not subject to due process but confined simply based on their ethnicity.

There is no reason to suppose that these precedents won’t be re-enacted in Ukraine.

Even this early in the conflict, there is a formidable number of combatants in the field and, assuming major Russian advances. It is highly likely that large numbers of people will be rapidly incarcerated.

The reasons are, firstly, the high number of combatants. Ukrainian regular forces, at c.209,000, already outnumber the forces that Russia has amassed for the invasion. To these can be added some 90,000 reservists and a surge of volunteers and paramilitaries.

Second, there is the status of these various combatants. We know from the wars in Chechnya, Georgia, and in the last eight years in Ukraine, armed combatants captured in the battlefield will be treated by Russia as zaderzhanye (detainees), not prisoners of war. The aims of Putin’s “special military operation”, to which nobody is allowed to refer as a war, is demilitarization and (absurdly) denazification. His rhetoric has already downgraded the Ukrainian professional armed forces to the status of terrorists, while the status that will be afforded to paramilitaries, volunteers, and the civilians who aided in the making petrol bombs, for example, is unclear.

Thirdly, as explained in a RIA Novosti article of a few days ago, because the Ukrainian population suffers from a generalized case of the Stockholm syndrome, after their liberation, “of course, a whole complex of measures will be required to bring this mentally unhealthy population to their senses.” Where, one is forced to conjecture, will this re-education take place for Ukrainians who are too slow coming to their senses other than in camps.[viii]

We can predict the emergence of a spontaneous incarceration system, which will amount to a system of camps. It is likely that Russia will want to move prisoners. en mass to penal colonies deep inside Russia. Were this to be the case, there would still be holding sites, assembly points, transit camps inside Ukraine.

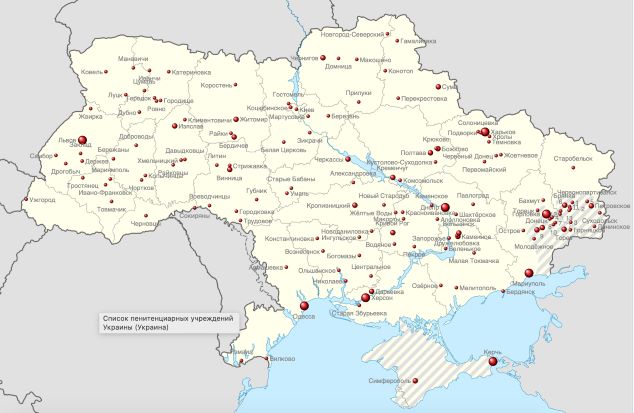

Map of penal facilities (pre-trial prisons and correctional colonies of categories) in Ukraine prior to the 2022 invasion by Russia.

The facilities in LPR and DPR are those officially listed by the Ukrainian prison service. The count does not include the allegedly numerous FSB ‘secret facilities’ and other carceral spaces that have been used since 2014 to confine regime opponents and captives.

[i] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1563747/russia-at-risk-of-expulsion-from-council-of-europe-chief

[ii] Greece under military rule left of its own accord in December 1969, and rejoined in 1974 after the fall of the junta.

[iii] https://ru.krymr.com/a/uzniki-za-veru-krym-delo-25-chast-1/31505464.html

[iv] This is longer than the journey convicts were taken from England to Anthony van Diemen’s Land’s land (Tasmania).

[v] The total has more than halved since 2000 from 1,060,404 today’s 464,183.

[vi] The higher figure takes into account the estimated 180,000 prisoners currently serving sentences who, according to official soruces, can now apply to be ‘released’ to serve the rest of their sentences under the new punishment of “forced labour as an alternative to deprivation of freedom’ living in a barrack in a correctional centre located on the BAM or in the Artic or, if they are lucky, in their own region.

[vii] Milica Stojanovic, BIRN, February 25, 2021

[viii] https://ria.ru/20220302/ukraina-1775974455.html