Author: John Westmoreland

Aunt Molly Jackson & T-Bone Slim:

At the Crossroads of Art & Research

Part 2: Who Is Aunt Molly Jackson?

My role as a musician, independent researcher, and relative of T-Bone Slim places me at a unique crossroads of art, research, and family history. With that perspective in mind, in this three-part blog series, “Aunt Molly Jackson & T-Bone Slim, at the Crossroads of Art & Research,” I share my thoughts on the origins of a mysterious folk song, the fascinating woman who wrote it, the relationship between folklorist and informant, and how this research relates to T-Bone Slim. Stay tuned for a new recording and video release at the end of Part 3.

In Part 1 of the series, I discussed a fascinating song, “Crossbones Scully,” written by Kentucky folk singer, Aunt Molly Jackson—allegedly about T-Bone Slim. In this second part I take a wider view of Aunt Molly’s life history and try to contextualize her artistry and activism in relationship to political ideology.

Born Mary Magdalene Garland—but using “Molly” as a first name—Aunt Molly Jackson grew up amid the cultural and socioeconomic environment of rural southern Appalachia at a time when grave exploitation of workers was institutionalized by the mining industry. Low wages paid in “scrip”—which could only be used to purchase inflated goods at the company store—as well as the practice of deducting extraneous expenses directly form a miners paycheck left many workers and their families in dire circumstances. Hunger, disease, and egregious safety standards in the mines contributed to high mortality rates amongst the population.

At the age of twelve, Molly began serving her community as a nurse and midwife which earned her the affectionate title “Aunt Molly”. Customarily midwives were referred to as “Granny” but being so young “Aunt” was thought to be a better fit in her case. Claims have been made by Aunt Molly and others that she delivered hundreds or even thousands of infants during her years as a midwife. She herself married twice before the age of twenty, and is believed to have had two biological children both of which died in infancy. Her second husband, Jim Stuart, was killed in a mining accident circa 1917 and soon after she married another coal miner, Bill Jackson, whose last name became part of her official identity as a folk singer for the remainder of her life.

“People just opened their mouths like the birds in the trees, and whatever melody come to them and whatever was on their minds, they just sang it out and that’s a folksong.”—Aunt Molly Jackson (Romalis 1999, 159)

Steeped in the traditions and lore of the Kentucky mountains, learning songs and stories passed down from older relatives—“knee to knee” as it’s been called in Appalachia—Aunt Molly Jackson began composing her own songs at the age of four. However, she would have likely remained an obscure figure were it not for the activism of the Dreiser Committee (also known as the NDPP) during the early days of the Harlan County War (see also the Raye 2020). Authors Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos and other prominent communist intellectual figures from New York City traveled to Harlan County in the fall of 1931 to document and raise national awareness about the conditions of exploitation and oppression unfolding in Kentucky. On November 7th, 1931 Aunt Molly attended a gathering at Glendon Baptist Church in Bell County and gave her own testimony to the committee, after which she proceeded to burst into song, belting out a version of her “Hungry Ragged Blues.” The performance left such an impression on Dreiser that he felt she would make an ideal symbolic representative for the miners’ cause. Aunt Molly through her appearance, manner, and actions projected a rural Appalachian cultural authenticity that was lacking in a movement comprised of urban intellectuals from the north.

“These women grabbed the gun thugs and stripped them naked while some of the local men took off through a cornfield after the strikebreakers. After four women had managed to hold down one of the gun thugs, my sister Molly took his pistol and shoved the barrel right up his rectum. Never did this particular gun thug show his face there again.”—Jim Garland (Romalis 1999, 86–87; about gun thugs see Raye 2020)

Aunt Molly, for her part, seemed happy to go along with Dreiser’s vision. She accepted an invitation from members of the Dreiser Committee to travel to New York City in an effort to help raise funds and publicity for the cause. It’s also been alleged that after Aunt Molly’s performance of “Hungry Ragged Blues,” she was arrested and only released by Judge David Crockett Jones on the condition that she leave Kentucky, so perhaps there were compounding factors which led to her exodus from the Appalachian coal country. (Collett 2006)

Communism & the IWW

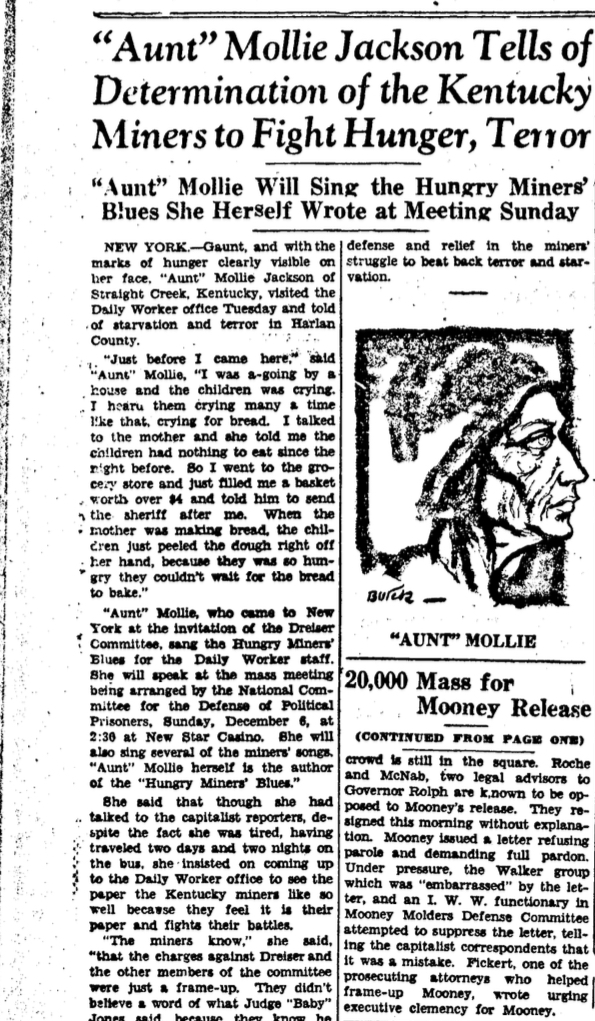

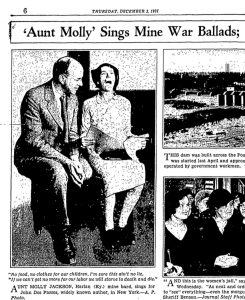

In late November of 1931, Aunt Molly Jackson boarded a northbound bus headed for New York. Upon her arrival on December 1st, she was thrust into the public eye. Many newspaper articles were published about her, and on a couple of occasions she performed for crowds of workers numbering in the thousands. She also went on a performance and speaking tour, collecting money to send back home to the striking miners in Harlan and Bell Counties. Many of these public events were organized as communist gatherings, and as such Aunt Molly was on the fringes of mainstream society despite receiving publicity in major press outlets such as the New York Times. Her own relationship to the communist party however appears to be opaque.

“The only ism we knew in Kentucky was rheumatism; I never heard tell of such thing as a communist or a radical until I was 50 years old when I come to New York. I got all of my progressive ideas from my hard, tough struggles and nowhere else.”—Aunt Molly Jackson (Wilgus 1961)

Whether or not her assertion about learning of communists and radicals only after leaving Kentucky is literally true, Aunt Molly’s point that her ideas and values come from her own life experience and not any ideology is certainly believable. By late 1931 however, she did have connections to communist circles, and some of her songs carry overt references to Communist organizations such as, “I am a Union Woman,” with a refrain that states “Join the NMU, come join the NMU.” The NMU (National Miners Union) was a Communist union which attempted from 1931–1932 to organize rural miners in Kentucky—an effort which met with limited success (on NMU see Soodalter 2016).

Interestingly, a December, 1931 issue of the Communist newspaper, the Daily Worker, features an interview with Aunt Molly as well as a separate article disparaging the IWW’s and UMWA’s (United Mine Workers of America) organizing efforts in Kentucky.

“The UMWA and the IWW are betraying us (– –) Now, when we are once more organizing, under the National Miners Union leadership, to strike against starvation, the UMWA and the IWW are again trying to step in in order to betray us. We must be on guard against these agents of the coal operators.”—Unknown author (Daily Worker, 2 December 1931)

T-Bone Slim, in his writings for the IWW in late 1931 also commented on the events in Kentucky, such as the following statement from the IWW’s Industrial Worker, published the very same day that Aunt Molly Jackson made her pivotal performance for the Dreiser Committee.

“There is no such thing as freedom of silence. No man has the right to contain in himself the thought, the knowledge, the experience, the eloquence, the prestige that might remove injustice from our fair land ( that might arrest the so called legal murders now in the making in the state of Kentucky…”—T-Bone Slim (Industrial Worker, 7 November 1931)

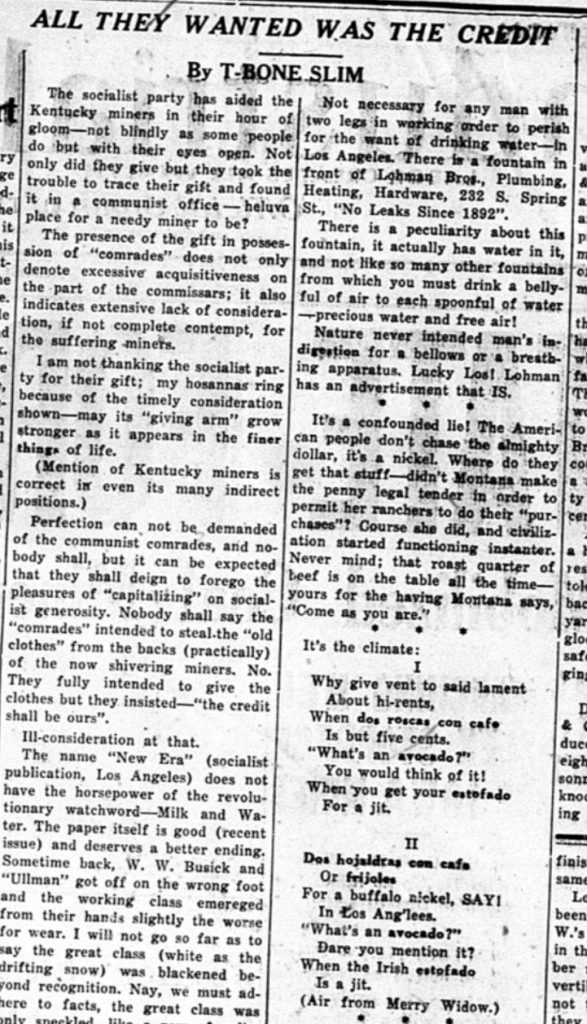

Days later in an article for another IWW periodical, Industrial Solidarity, we find T-Bone Slim weighing in on the subject of aid for the striking workers in Kentucky in relationship to the activities of Socialists and Communists.

“The socialist party has aided the Kentucky miners in their hour of gloom—not blindly as some people do but with their eyes open. Not only did they give but they took the trouble to trace their gift and found it in a communist office—heluva place for a needy miner to be? The presence of the gift in possession of ‘comrades’… indicates extensive lack of consideration, if not complete contempt for the suffering miners.” T-Bone Slim (Industrial Solidarity, 17 November 1931)

The above excerpts quoted from the Daily Worker and T-Bone Slim’s Industrial Solidarity column exemplify the distrust, and animosity which sometimes characterized the dynamic between the Communist Party and the IWW. Folklorist Archie Green’s skepticism that Aunt Molly ever truly met T-Bone Slim derives largely from his awareness of that tenuous historical relationship.

“Plainly put, IWW’s and communists during sectarian years, worked together on various jobs, but did not fraternize in meetings or social events. At times, the ideological differences between them led to bloodshed. Many Wobblies were among the earliest critics of Stalinism on the American left. Communists responded both by denigrating, anarchist values and appropriating Wobbly lore.”—Archie Green (Archie Green Collection, SFC)

Putting aside Archie Green’s skepticism for the moment, it’s important to mention that both T-Bone Slim and Aunt Molly Jackson lived in New York City during the 1930’s and early 1940’s. In a geographic sense it’s certainly not out of the question that they could have crossed paths, and Green himself acknowledges that regardless of ideological tensions between the IWW and the Communist Party, it’s not impossible the two songwriters met.

Further evidence that perhaps T-Bone Slim did have some connection to communist MWIU members can be found in an anecdote from Communist MWIU organizer, Al Lannon, who claimed that T-Bone Slim was invited to perform at a 1933 Communist event in New York City.

“Hoping to capitalize on lingering IWW sentiment among seamen, Lannon set up an open-air meeting at Thames and Broadway featuring T-Bone Slim. Lannon gave the singer a big introduction, expecting the singer to open with his well-known ‘Popular Wobbly.’ T-Bone Slim began yelling at the crowd about ‘those fuckin’ bastards down in Alabama’ who had framed the Scottsboro Boys. An embarrassed Lannon hustled the living legend, away from the microphone. They later made T-Bone Slim, an honorary member of the Port Organizing Committee, allowing him to sell The Marine Workers Voice along the waterfront.” (Lannon 1999, 45–46; about the Port Organizing Committee see Bailey 1993)

Al Lannon’s assertion is quite interesting—especially the bit about T-Bone being pulled off stage—if true it certainly lends credibility to Aunt Molly Jackson’s claim that she met T-Bone Slim in person. I’m somewhat skeptical that T-Bone Slim ever became a member of the Port Organizing Committee and sold Communist newspapers on the New York waterfront, but if further supporting evidence comes to light my opinion is of course subject to change. Archie Green speculated in some of his writings on the topic of “Crossbones Scully,” that Aunt Molly Jackson may have been attempting to “misappropriate” the identity of an IWW hero (Archie Green Collection, SFC), the same question could be asked of Al Lannon’s claim. Ultimately, the veracity of either or both Aunt Molly’s and Al Lannon’s T-Bone Slim encounters may never be known, it could be impossible to prove whether these stories are completely true, completely fabricated, or partially true and partially fabricated.

In part 3 of the series I will discuss archival recordings of “Crossbones Scully,” the relationship between Aunt Molly Jackson and the folklorists who studied her, and release a new video of the song filmed in studio during production of my forthcoming T-Bone Slim album, Resurrection.

Archival References:

Archie Green Collection at UNC Chapel Hill’s Southern Folklife Collection (SFC)

Book References:

Author Unknown. (1942). The Kentucky Miners Struggle. New York City, New York: American Civil Liberties Union.

Bailey, Bill. (1993). The Kid from Hoboken: An Autobiography. San Francisco, California: Circus Lithographic Press.

Lannon, Albert. (1999). Second String Red. Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: Lexington Books.

Romalis, Shelly. (1999). Pistol Packin’ Mama. Champaign, Illinois: Univeristy of Illinois Press.

Journal References:

Collett, Dexter. (2006). “The Musicians of the Mine Wars.” Appalachian Heritage 34 (2): 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/aph.2006.0019.

Wilgus, D. K. (1961). “Aunt Molly Jackson Memorial Issue.” Kentucky Folklore Record 7 (4): 129–176. https://doi.org/10.2307/836303.

Website References:

Raye, Janet. (2020). “Hellraisers Journal: Company Gunthugs Beat Up and Shoot Down Union Coal Miners in Harlan County, Kentucky”. Hellraisers Journal. May 14, 2020. https://weneverforget.org/hellraisers-journal-company-gunthugs-beat-up-and-shoot-down-union-coal-miners-in-harlan-county-kentucky/

Soodalter, Ron. (2016). “The Price of Coal Part II”. Kentucky Monthly. October 31, 2016. https://www.kentuckymonthly.com/culture/history/the-price-of-coal_1/