Author: John Westmoreland

Aunt Molly Jackson & T-Bone Slim:

At the Crossroads of Art & Research

Part 3: Recording “Crossbones Scully” Then & Now

Featuring a new in studio video release!

My role as a musician, independent researcher, and relative of T-Bone Slim places me at a unique crossroads of art, research, and family history. With that perspective in mind, in this three part blog series, “Aunt Molly Jackson & T-Bone Slim, at the Crossroads of Art & Research,” I share my thoughts on the origins of a mysterious folk song, the fascinating woman who wrote it, the relationship between folklorist and informant, and how this research relates to T-Bone Slim.

In Part 1, I introduced the song and its composer, Aunt Molly Jackson. In Part 2, I discussed Aunt Molly’s biographical history, her connection to the Communist Party USA, and tensions between the IWW and Communists. This final part of the blog series will be an examination of the historical recordings of “Crossbones Scully,” release of my new in-studio recording/video of the song, and a discussion of the relationship between the Kentucky folk singer and the folklorists who studied her.

1939 Recordings

While the precise date of composition is unknown, famed folklorist and song collector, Alan Lomax, recorded two renditions of Aunt Molly singing “Crossbones Scully” in New York City during the spring of 1939. These a capella recordings are available online through the American Folklife Center (AFC) at the Library of Congress, catalogued as AFS 2539B and AFS 2556A respectively. The acetate disc jacket sleeve notes for AFS 2556A state that Molly’s half brother, Jim Garland, suggested the name and that “Molly says it was inspired by T-Bone Slim’s stories.” From this documentary evidence we know that Aunt Molly was claiming the song was about T-Bone Slim as early as 1939, and apparently her brother chose the title. Two other versions of the song were recorded by Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in the fall of 1939, her recordings are catalogued as Disc 155, side B, and Disc 157, Side A at the Archives of Appalachia. Notably, Barnicle’s jacket sleeve documents the song’s title as “T-Bone Scully.”

![Image of a paper with a scanned image of the jacket sleeve. There's some handwriting on the sleeve: " 22) A) Crossbones Scully (This name suggested by [unclear name] - Molly says t was [unclear] by T-Bone Slim's stories). [unclear] "Oh twll me how Iäll have to wait for a job," variant melofy - Hentation [?] Blues. B) The [unclear] Ranger (my father's favorite son [unclear] want to sing it as [unclear] like him as of can).](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/tboneslim/files/2023/05/P3.-Fig.-1-1939Recording-Jacket-1024x768.jpg)

![Image of a paper with a scanned image of the jacket sleeve. There's some handwriting on the sleeve: "Aunt Molly Jackson, 19 Oct. 1939. 1. T-Bone Scully 2. Ma[unclear] had an old black cow. BC 157. #212."](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/tboneslim/files/2023/06/P3.-Fig.-2-Disc-157-Side-A-Jacket-Sleeve.png)

Pseudonyms & Monikers

During his lifetime, Matti V. Huhta made use of a number of pseudonyms in addition to the moniker T-Bone Slim, but no evidence has surfaced that “Crossbones Scully” was ever one of them, and my own efforts thus far have not discovered a single reference to anyone using the appellations “Crossbones Scully,” or “T-Bone Scully.” Furthermore, T-Bone Slim research to date has not uncovered any court records or stories—other than Aunt Molly’s own account—of Matti V. Huhta serving a jail sentence for beating up and robbing a “rich old geezer.” The gaps in the current biographical narrative of T-Bone Slim’s life are substantial though, so it’s likely there are significant events which remain unknown. New findings indicate that he did spend time behind bars on at least two occasions, and an undated letter written to his sister Sofie—my great grandmother—sometime during the last decade of his life states, “My case is coming up next Friday; so pull for me hard. Of course I win—now or later.” The letter indicates a great deal of concern and a sense of injustice that will be made right in the future if not in the present. He signs the letter, “Joe Hilger,” a pseudonym which invokes the memory of Joe Hill, the most legendary IWW martyr who was killed by firing squad on November 19th, 1915 in Utah.

The Folklorists & The Folk Singer

“Aunt Molly’s Truth was often greater than the facts.”—John Greenway (Wilgus 1967)

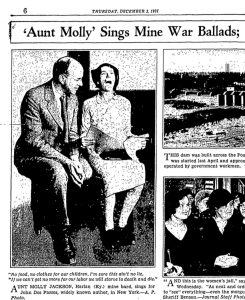

During her lifetime, Aunt Molly Jackson was interviewed and studied by many folklorists including Alan Lomax, Archie Green, Mary Elizabeth Barnicle Cadle, and John Greenway. Many if not all of these scholars and song collectors came to view her as an “unreliable informant,” who at times fabricated events and claimed authorship of songs composed by others. Still, their respect for her as a genuine representative of folk tradition and as a tireless fighter for the working class and poor was not diminished.

“She was folklore itself, at its best, and its best is that it won’t stop growing, and it can’t be beaten. We won’t see her like again ever, now….”—Alan Lomax (Wilgus 1967).

![Black and white newspaper clip portraying five men standing and leaning towards sitting Aunt Molly Jackson. They seem to be singing. Image caption: "Hillbilly turns collegiate- Aunt Molly Jackson, Kentucky mountain ballad singer, leads a class of New York university folk culture students in singing one of her own mountain ballads. The pipe-smoking hillbilly has composed several songs, and delights in telling the story of how she "made up" the ballad "Mr. Cundiff, Won't You Turn Me Loose?" when she was thrown into jail at the age of 10. That song, according to Molly, won over the jail and [blank] also several plugs of chewing tobacco for her."](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/tboneslim/files/2023/06/P3.-Fig.-4-Aunt-Molly-Greensboro-Daily-News-Photo.jpeg)

![Handwriting on a paper. "Sep the 2 1939 NYC. mr alan lomax is ancer to your letter i am not interested in you useing eney of my story or songs as i am riting a book of my own i want to use all of my songs an storys in my own book, so do not [unclear] eney of my songs or story, whatever you do if you so i am shure you will be sariy [?] from molly jackson [address unclear] NYC"](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/tboneslim/files/2023/06/P3.-Fig.-5-Aunt-Molly-1939-Letter-to-Alan-Lomax-666x1024.png)

“Molly’s truths fell by collectors’ and folklorists’ waysides, unvalidated, discredited. How do I, as a writer of their stories, know who to believe? Does the truth of one mean the lies of another? We know that everyone remembers selectively, fictionalizes, informants, and writers alike; as scholarly gatekeepers, we and our editors (not our informants) have the final say in published words.” (Romalis 1999, 197)

The song “Crossbones Scully” was documented by at least four of the folklorists who collected Aunt Molly’s songs—Alan Lomax, Mary Elizabeth Barnicle, John Greenway, and Archie Green. Unfortunately, none of them took enough of an interest in the ballad to question her about its subject matter and origins in any detail.

“To put it bluntly, the ballad may not have appealed to any listeners… Molly’s account troubled me in 1957, but did not lead me to undertake a detailed case study. Her ballads, awkward lines, weak plot, and dated posture blocked the opening that might have spurred my study… ‘Crossbones Scully’ does not rank with aunt Molly‘s best ballads. We find no evidence that it entered tradition, or that she prized it after leaving New York.”—Archie Green (Archie Green Collection, SFC)

So why did Aunt Molly perform “Crossbones Scully” for both John Greenway in 1951, and Archie Green in 1957 if she didn’t value the song, almost two decades after recording it twice for Alan Lomax and twice for Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in 1939? Green speculated that Greenway likely heard the Lomax recordings thus peaking his interest in the song and leading him to ask Aunt Molly about it. However, the transcript of Archie Green’s own interview with the Kentucky folk singer perhaps indicates another possibility—that Aunt Molly may have brought up “Crossbones Scully” of her own accord simply because she felt it was an important song.

“Archie Green: Aunt Molly, of all the songs that you wrote, which song became best known to other people. People outside of Kentucky. Other students and singers. Which is your most popular song Aunt Molly?

Molly: You mean that I wrote myself? Well, always what I’d go to these musical divisions of the colleges to entertain. After they found out that I had wrote that song its in the book maybe Jim named it T Bone Skully that song. That’s a day we’d had a big seaman strike in New York and we had a big party to collecting funds for the seamen and I met this here T Bone Slim. I composed a song from that and he told me he said I laughed so about that he said aunt Molly, he says. I’m ___ that big top silk hat on my head and that suit and he says my old ragged shoes. And dog gone me he says I’m taking the old geezer’s shoes off, and I aim to throw my old ragged shoes down here come a dog gone police man he says. And they give him a year and one day for that.”—Archie Green & Aunt Molly Jackson interview (Archie Green Collection, SFC)

![Typed text on a paper. "Tape #2838 song I said sadly blow that weeping willow, just like me it's stands alone. I have had no one to love me since my mother's dead and gone. I was seven then. A.G.: That's a beautiful song. Molly: Oh it is beautiful. I got all the words written. A. G.: Aunt Molly, of all the songs that you wrote which song became the best known to other people. People outside of Kentucky. Other students and singers. Which is your most popular song Aunt Molly? Molly: You mean that I wrote myself? Well always I'd go to these musical divisions of the colleges to entertain. After they found out that I'd wrote that song its in the book maybe Jim named it T Bone Scully ["T Bone Scully" underlined] that song. That's a day we'd had a big seaman strike that ["that" crossed over] in New York and we had a big party to collecting funds for the seamen and I met this here T-Bone Slim ["T-Bone Slim" underlined] Side B: I composed a song from that and he told me he said I laughed so about that that he said Aunt Molly he says. I'm [blank] that big top silk hat on my head and that suit and he says my old ragged shoes. And dog gone me he says I'm taking the old geezers shoes off and I aim to throw my old ragged shoes down here come a dog gone police man he says. And they give him a year and one day for that. Interviewer: Could you just give us the first few lines of that. How it went? Molly: I want to tell you firsta about that. So they foun ["they foun" crossed over] after they found out in these places you know Charles Haywood ["Charles Haywood" underlined] if he was in the musical [ends in the middle of the sentence]"](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/tboneslim/files/2023/06/P3.-Fig.-8-Archie-Green-Aunt-Molly-Transcript-827x1024.jpeg)

Aunt Molly Jackson died in 1960. Many years have passed and all of the folklorists who knew her and documented her life and music are also deceased. No scholars ever made a study of “Crossbones Scully” or took much interest in the song during the lifetime of its author, and it may be unlikely that any new evidence of its origins will come to light. Therefore, we are left mostly with speculation. Do we take Aunt Molly’s word that she met T-Bone Slim and wrote a song based on factual or at least partially factual events? Did she make up the narrative out of whole cloth but choose T-Bone Slim’s identity to be the fictional protagonist—before or after she composed the song? Is there a hidden story behind “Crossbones Scully” as Archie Green believed?

I’ve spent many hours going down the “Crossbones Scully” rabbit hole, and researching Aunt Molly Jackson. Ultimately, I don’t know if she ever met my great granduncle, but I found the mystery surrounding her song to be intriguing and compelling enough of a reason to make a new recording of “Crossbones Scully” for my upcoming T-Bone Slim album, Resurrection. You can check out a live in studio video of the song at the YouTube link below. It was a unique recording experience for myself and the other musicians because we actually played along to Aunt Molly Jackson’s AFS 2539B recording from 1939, accompanying her voice with our instruments. I hope Aunt Molly would approve of this posthumous collaboration, it’s meant to pay homage to her music and legacy. I’m keeping my fingers crossed that we didn’t “mommick” it up…

Video: John Westmoreland’s recording of “Crossbones Scully” with violinist Jennifer Curtis, and bassist Ron Brendle. Recorded Live at Overdub Lane Studio in Durham North Carolina.

Archival References:

Archie Green Collection at UNC Chapel Hill’s Southern Folklife Collection (SFC)

American Folklife Center Archives (AFC)

Aunt Molly Jackson Kentucky Lomax Recordings Collection

Mary Elizabeth Barnicle & Tillman Cadle Recordings Collection at East Tennessee State University’s Archives of Appalachia

Book References:

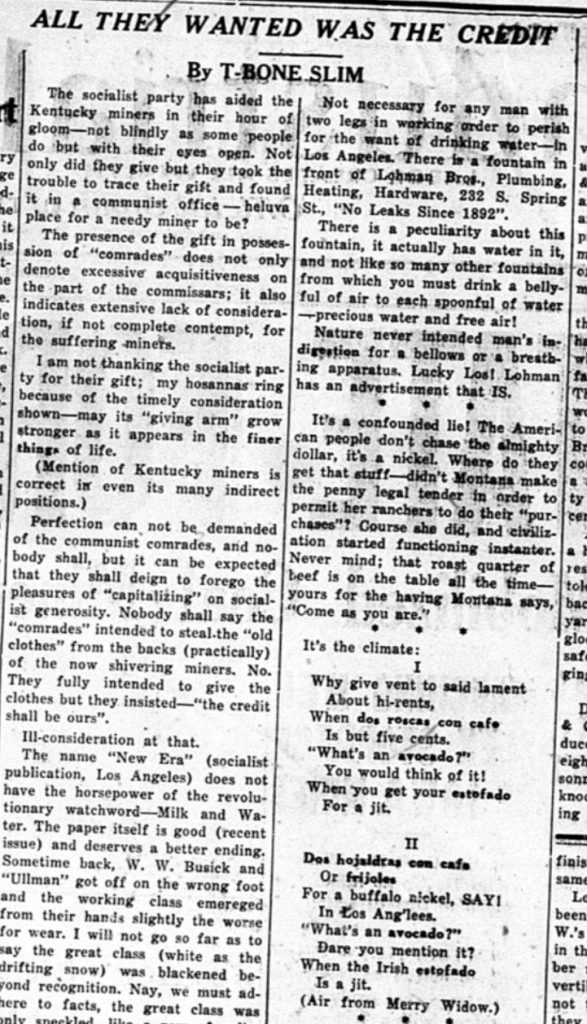

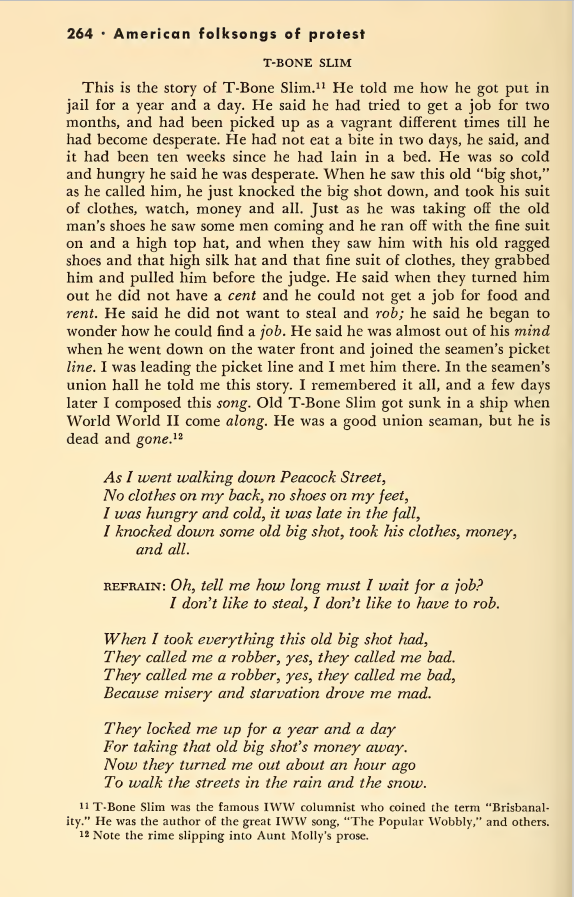

Greenway, John. (1953). American Folk Songs of Protest. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Romalis, Shelly. (1999). Pistol Packin’ Mama. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Journal References:

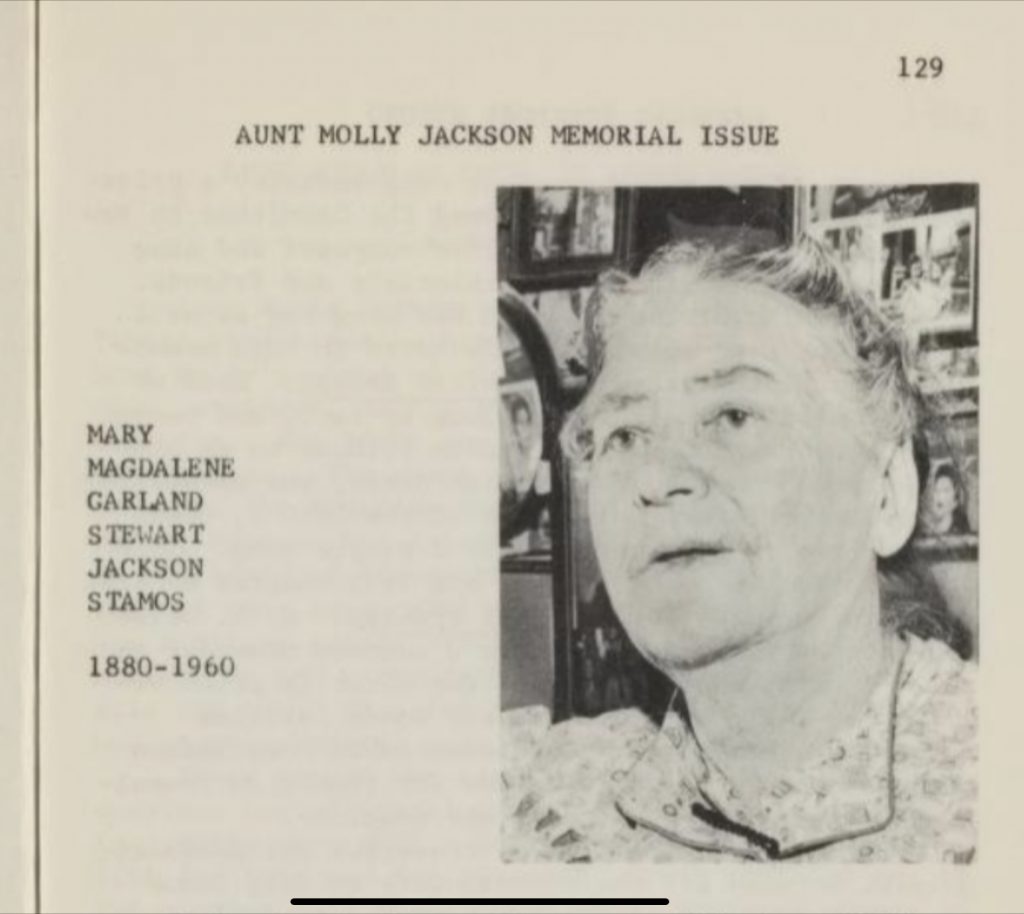

Wilgus, D. K. (1961). “Aunt Molly Jackson Memorial Issue.” Kentucky Folklore Record 7 (4): 129–176. https://doi.org/10.2307/836303.