Author: John Westmoreland

Aunt Molly Jackson & T-Bone Slim:

At the Crossroads of Art & Research

Part 1: The Mystery of “Crossbones Scully”

“Who can rescue Molly’s ‘Crossbones Scully’ from obscurity? Who will pose fresh questions about its meaning to present day guardians of radical tradition?… In my view, the hidden story behind Aunt Molly‘s ‘Crossbones Scully’ is more intriguing than the narrative of a poor sailor robbing a rich geezer.” —Folklorist Archie Green (Archie Green Collection, SFC)

My role as a musician, independent researcher, and relative of T-Bone Slim places me at a unique crossroads of art, research, and family history. With that perspective in mind, in this three-part blog series, “Aunt Molly Jackson & T-Bone Slim, at the Crossroads of Art & Research,” I share my thoughts on the origins of a mysterious folk song, the fascinating woman who wrote it, the relationship between folklorist and informant, and how this research relates to T-Bone Slim. Stay tuned for a new recording and video release at the end of Part 3.

The song “Crossbones Scully” was composed by Kentucky folksinger and union activist, Aunt Molly Jackson (1881–1960), who became a forceful advocate for the plight of impoverished coal miners and their families in Eastern Kentucky during the 1930’s. Folk music icons such as Pete Seeger have credited her as a major influence (Romalis 1999, 101), and Woody Guthrie once wrote that she was the “best ballad singer in the whole country.” (Guthrie 1967, 139)

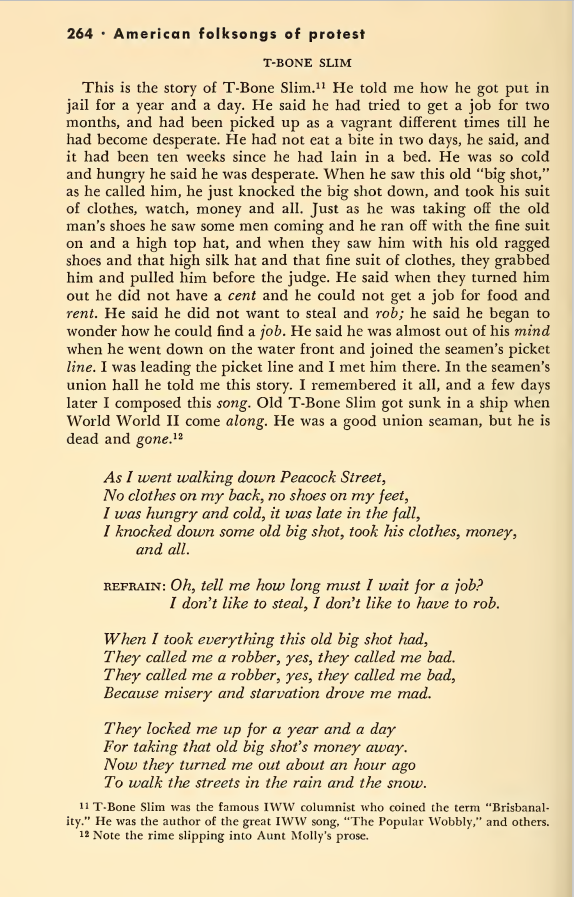

The title of Aunt Molly’s aforementioned song may to some readers bear a resemblance to the nom de plume of Matti V. Huhta—T-Bone Slim— the illustrious hobo, songwriter, poet, and IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) columnist. In fact the first publication of “Crossbones Scully” in print comes from folklorist John Greenway’s chapter on Aunt Molly for his 1953 anthology, American Folk Songs of Protest, which lists the title simply as “T-Bone Slim” (Greenway 1953, 264). A spoken word introduction Aunt Molly recited to Greenway during an interview in 1951 precedes the lyrics.

“This is the story of T-Bone slim. He told me how he got put in jail for a year and a day. He said he had tried to get a job for two months, and had been picked up as a vagrant different times till he had become desperate. He had not eat a bite in two days, he said, and it had been 10 weeks since he had lain in a bed. He was so cold and hungry he said he was desperate. When he saw this old ‘big shot,’ as he called him, he just knocked the big shot down, and took his suit of clothes, watch, money and all. Just as he was taking off the old man’s shoes he saw some men coming and he ran off with the fine suit on and a high top hat, and when they saw him with his old rags and shoes and that high silk hat and that fine suit of clothes, they grabbed him and pulled him before the judge. He said when they turned him out and he did not have a cent and he could not get a job for food and rent. He said he did not want to steal and rob; he said he began to wonder how he could find a job. He said he was almost out of his mind when he went down on the waterfront and joined the seamen’s picket line. I was leading the picket line and I met him there. In the Seamen’s union hall he told me this story. I remembered it all, and a few days later I composed this song. Old T-Bone Slim got sunk in a ship when World War II come along. He was a good union seamen, but he is dead and gone.”—Aunt Molly Jackson (Greenway 1953, 264)

The Story of T-Bone Slim?

While Aunt Molly Jackson’s introduction clearly indicates that her song is indeed about T-Bone Slim, it may be helpful to take a step back and consider a broader perspective of the song, the folksinger who composed it, as well as the folklorists who collected and studied Aunt Molly’s life and compositions.

“Let me confess that I can’t get this song out of my mind. All the forces that pushed me to ballad scholarship in the 1950s have converged again. Molly’s maritime song has become a metaphor for the questions I neglected to ask in visits with her.”—Archie Green (Letter to Shelly Romalis April 21st, 1992, Archie Green Collection, SFC)

In her introduction to “Crossbones Scully,” Aunt Molly is speaking in verse. In a sense it’s as if she’s already singing the song, and as such may be favoring musicality and rhyme over dry facts. In my view this versification adds an enigmatic and mysterious air to the narrative she describes. But to state it as plainly as possible, in “Crossbones Scully” we have the story of a desperate out of work sailor, cold and hungry, who comes across some wealthy old “big shot,” knocks him down, robs him, and as a result gets thrown in jail for a year and a day. Upon his release the sailor is still desperate and contemplates that out of necessity he may have to repeat his crime. Ultimately, the unlikely hero goes down to the waterfront and joins the seamen’s picket line which Aunt Molly is leading. The sailor recounts his story to her at the seamen’s union hall and she composes a song out of it. Aunt Molly concludes her introduction stating “Old T-Bone Slim got sunk in a ship when World War II come along. He was a good union seamen, but he is dead and gone.” As Franklin Rosemont pointed out in the biographical introduction of his anthology Juice is Stranger Than Friction: Selected Writings of T-Bone Slim (1993), it’s factually inaccurate to say that T-Bone Slim’s ship was sunk during World War II. Rather, he fell, was murdered, or jumped off, and the boat itself—a scow—was certainly not sunk. That being said, in a more poetic sense, could it be—as Rosemont considers a possibility—that Aunt Molly is tying T-Bone Slim’s demise to the US entry into World War II?

Fellow researcher Dr. Saku Pinta noted in his blogposts, Who Killed T-Bone Slim Part I & Part II, that the last published article of T-bone Slim’s career appeared in the Industrial Worker on April 4th, 1942. Within that article references are made to the blackout drills which had begun to take place in New York at the end of 1941.

“To say the least, blackout is a promise, a prophecy, foreboding eternal darkness.”

“When New York City is bombed, say May 10-20, you may be sure I will not run.”

T-Bone Slim’s body was found floating in the East River at Pier 9 in Manhattan on May 15th. The question arises, is it a coincidence that T-Bone Slim’s final article speaks of “prophecy,” “foreboding eternal darkness,” and a bombing between May 10th–20th which happens to coincide with the time frame of his own death? Is it possible that in a veiled manner T-Bone is ominously predicting the end of his own life? Dr. Pinta’s blogposts offer thoughts and reflections on the matter including consideration of the possibility that T-Bone Slim’s death could have been connected to the US intelligence collaboration with organized crime on the waterfront of New York City, ”Project Underworld,” which began in the spring of 1942. Bearing this additional information in mind, I do wonder whether Aunt Molly’s account of T-Bone Slim’s ship being sunk “when World War II come along,” might be a metaphor implying he was murdered and that somehow his death was related to the onset of US involvement in WWII. Of course, another possibility is that it’s simply a poetic way of mourning the loss of a sailor.

Despite Aunt Molly’s introduction to “Crossbones Scully” in John Greenway’s, American Folk Songs of Protest, another distinguished folklorist, Archie Green, has cast doubt on the idea that she ever truly met T-Bone Slim and wrote a song about him.

“I am uncertain whether Molly had actually met T-Bone Slim and heard him tell a story about going to jail after robbing a big shot, or had read such an account in either an IWW or CP (Communist Party) publication, or had heard the anecdote from a third person.“—Archie Green (Archie Green Collection, SFC)

In Part 2 of this three-part series I will explore the background and biography of Aunt Molly Jackson, her ideological affiliation, as well as the divisive relationship which existed between the IWW and the Communist Party USA.

Archival References:

Archie Green Collection at UNC Chapel Hill’s Southern Folklife Collection (SFC)

Book References:

Greenway, John. (1953). American Folk Songs of Protest. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Guthrie, Woody. (1967). Hard Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Romalis, Shelly. (1999). Pistol Packin’ Mama. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Rosemont, Franklin. (1993). Juice is Stranger Than Friction: Selected Writings of T-Bone Slim. Chicago, Illinois: Charles H. Kerr Publishing.