AUTHOR: Marija Dalbello

From my Archival “Digs”

PART II: ENVELOPES

The Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) collection in the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Columbia University documents the immigrant working class struggle from a century ago. Most of the documents are from the period between 1916 and 1922, the time of unrest and war, I.W.W.-led strikes, strikers’ imprisonment, and trials. This atmosphere was echoed through the letters, letter-poems, and some envelopes (yes, envelopes!) leading back to L.S. Chumley, a “wobbly” activist and editor of the Rebel Worker.

Through their transmission, the envelopes’ surfaces can accumulate information such as postal markings and inscriptions. They record interpersonal epistolary exchange. The envelopes are the skins that transmit the correspondents’ touch alongside the letters’ writing, folding, sealing; then tearing, cutting, un-folding them, and reading. In the envelopes, epistolary texts travel — enclosed, safe, and protected. They rarely survive in archival contexts to document transmission. So, when possible, I like to examine them as evidence. I found three such envelopes in my “dig” that carried an ‘excess’ of meaning, real and imagined.

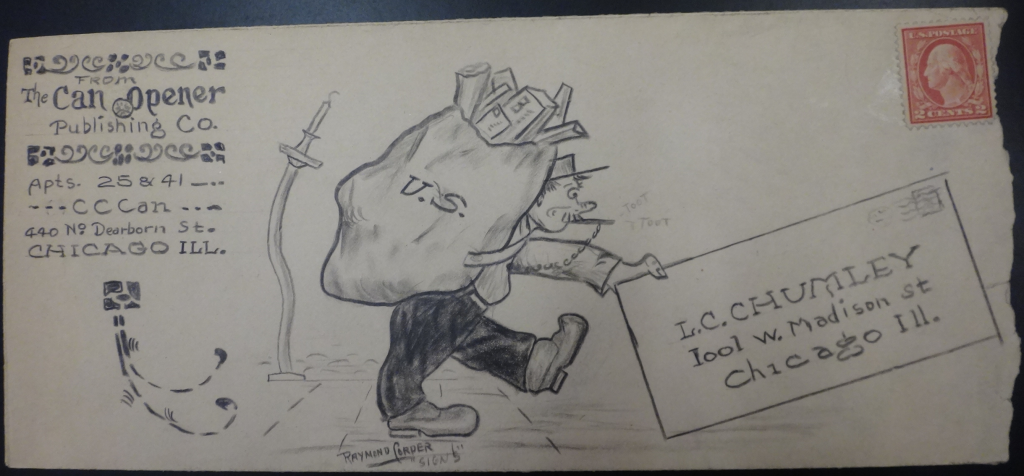

The First Envelope: A Drawing

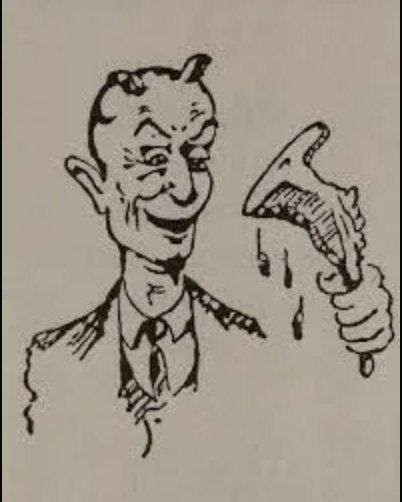

On the face of my first archival envelope is a pencil drawing in the style of I.W.W. satirical cartoons that depicts a mail carrier, whistling “Toot Toot,” a sack-full of packages on his back, hand-delivering a letter addressed to “L.C. [sic] Chumley” at 1001 W. Madison St. in Chicago, Illinois. The sender is “The Can Opener Publishing Co., Apts. 25 & 41, CC Can, 440 No. Dearborn St., Chicago, Illinois” (Fig. 1). This ‘publishing company’ was in the Cook County jail, its punned name a sarcastic reference to the ‘can’ (jail) and anything that could be ‘canned.’ The drawing is signed by Raymond Corder. This illustration makes it possible to imagine what this emptied out envelope contained. It could have been used by the ‘canned’ Wobblies to send their writings to Chumley. In the satchel or the envelope arriving to Chumley’s door could be any of the Wobbly letters or poems found in this collection. It could have been the narrative poem “Bisbee” (dedicated to the I.W.W. organized miners’ strike and deportation of over 1,000 strikers, their families, and other citizens in July 1917) including this message to the editor by someone who self-identified by their prison cell and the I.W.W. card numbers:

Dear Sir

How about it, too raw?

I would like to see this little reminder in the Rebel Worker

I am up against it or I would write you a decent letter

Yours truly

Card 575210 No. 300.

Alternatively, the emissary could be delivering the vision of another working-class poet Richard Brazier titled “The Girl Across the Way,” which he wrote in jail in the “year of conspiracy, 1917” and sent it to Chumley. Or it could be the prose poem, with the opening: “On Land or Sea wherever you may be stearing [sic] the ship in the tempests breath or behind prison bars of freedom bereft you who gain riches regardless of danger … ,” and closing: “To fellowworker Chumley. If you have use for this [,] put in the Rebel Worker Wigand Allen.”

The Second Envelope: A ‘Defaced’ Container

Browsing on, I find the envelope from Underwood’s News Photo Service series, World Events in Pictures. A diagonally placed note in black and red alerts to its intended contents (stereographs): “Press Matter, For Editor.” In branded stationery, the envelopes may ‘own’ their content but scribbled on its face is another message. I find the words “Secret Prison Newspaper” in a collector’s or archivist’s hand (Fig. 2). Intended for delivery of stock photos, it doubles as a container for prison journalism. This envelope was meant to keep, not send or receive.

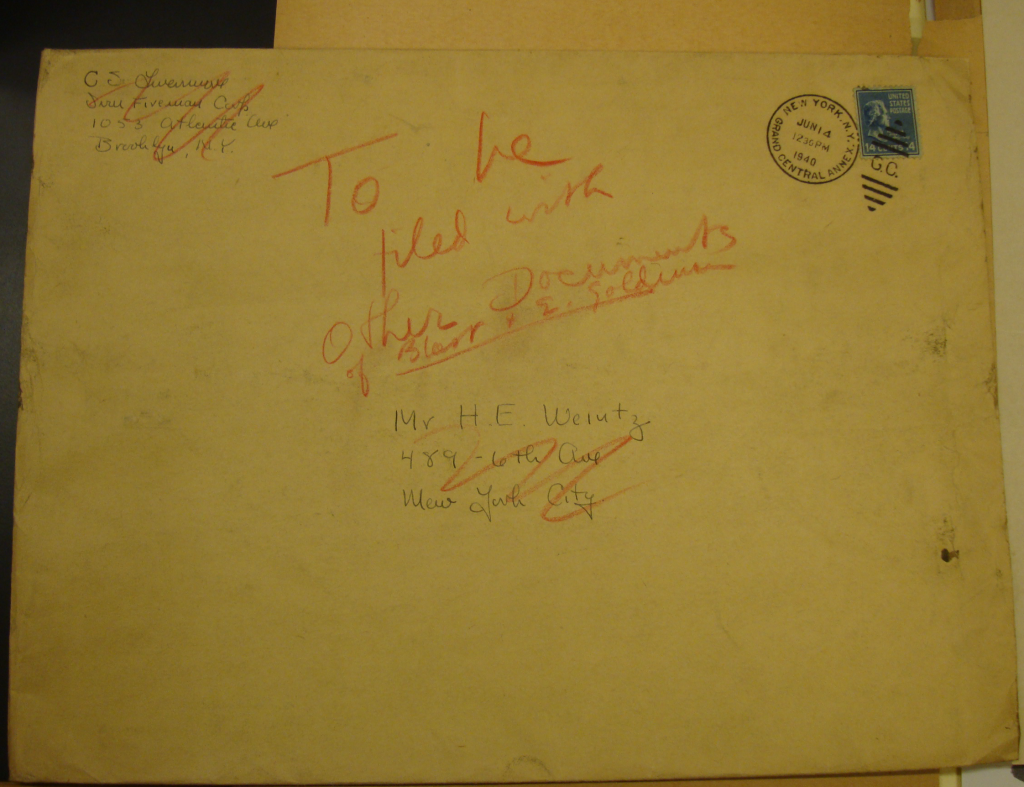

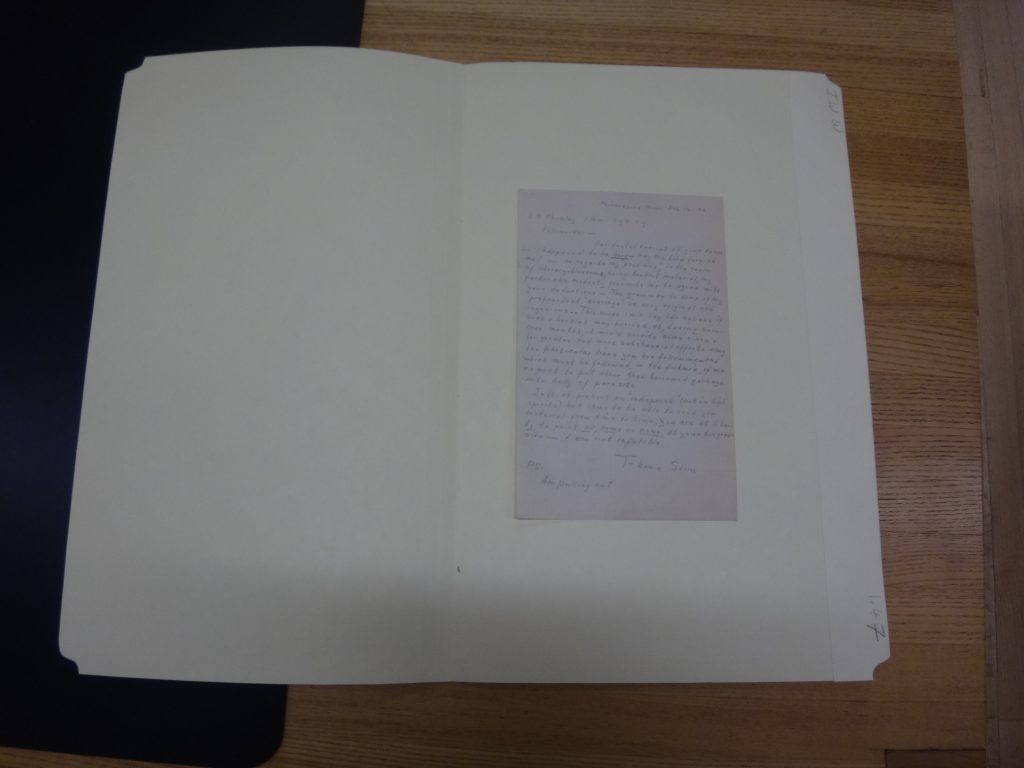

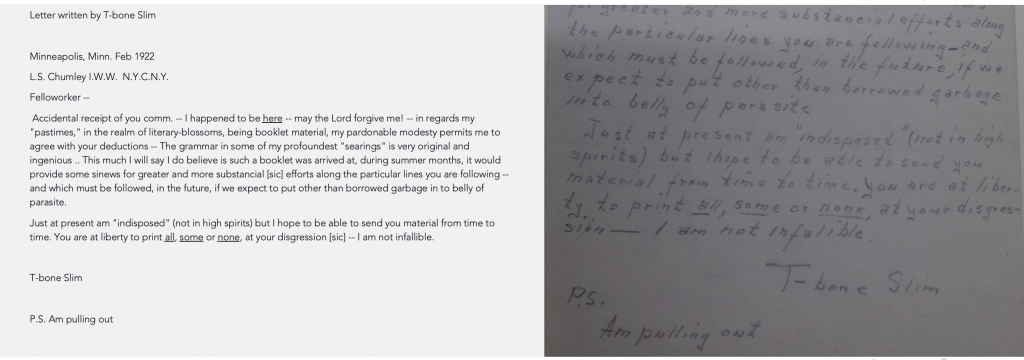

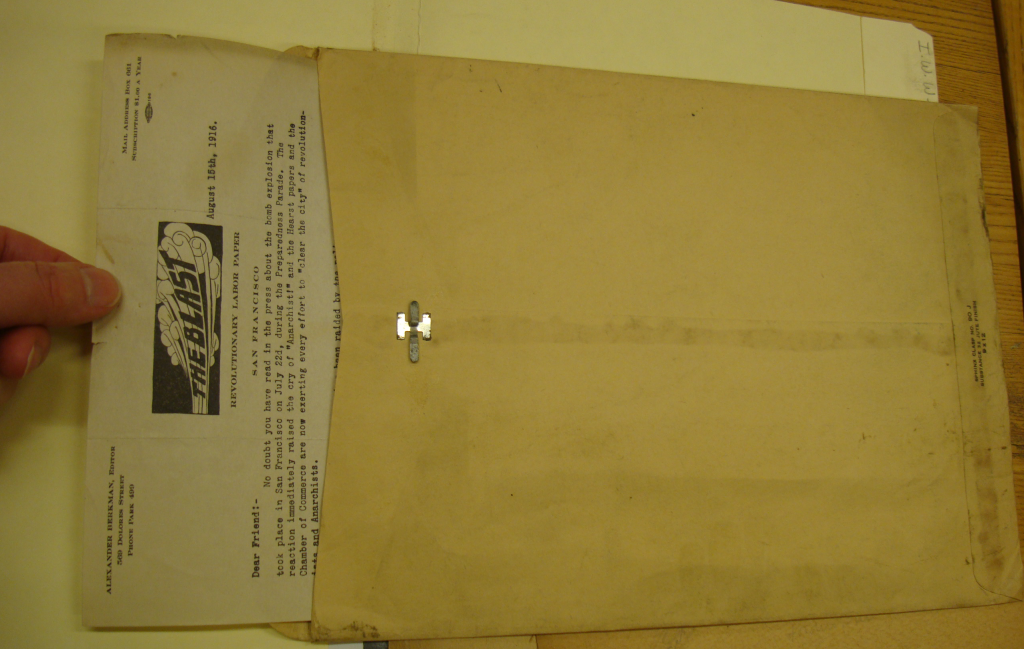

The Third Envelope: The Blast

Found in the archival folder labeled “Various envelopes,” is one postmarked 1940 with instruction to be filed “with other documents of Blast & E. Goldman” that, surprisingly, contained a letter. The letter was signed by Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, dated August 15, 1916. (Fig. 3a-b).

Hiding in this envelope was the appeal to save Berkman’s paper The Blast and informing the supporters of intimidation and raids suffered by the editorial staff and offices. This was written less than a month following the anarchist-suspected explosion in San Francisco on July 22, 1917, at a rally favoring the United States entering the war (IISH) and before the couple’s deportation on the “Red Ark” that left Ellis Island on December 21, 1919 (Minor 1919).

As archival materiality, envelopes are surfaces and containers. Like drawers or folders, they are anatomic structures epitomizing archival intimacy in which the researchers’ sensations attract micro-readings.

by MARIJA DALBELLO

=====

This is the second in the series of blogs From my Archival “Digs” that focus on archival stories. I relate to documents in the mode of “drifting” (Dalbello 2019) in order to present their histories but also the aesthetic emotions and sensations that characterize archival disclosures.

=====

References

Dalbello, Marija. (2019). “Archaeological Sensations in the Archives of Migration and the Ellis Island Sensorium,” Archaeology and Information Research, a special issue of Information Research 24 (2), http://informationr.net/ir/24-2/paper817.html. Accessed January 30, 2023.

Industrial Workers of the World collection, 1916-1922, https://findingaids.library.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-rb/ldpd_7072761. Accessed January 30, 2023.

International Institute of Social History. (1917-1919). FBI File on Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman Archives, https://search.iisg.amsterdam/Record/ARCH01724. Accessed January 30, 2023.

Minor, Robert. (1919). Introduction to Deportation: Its Meaning and Menace.

Preston, Louisa. (2022). Sketch of Marija Dalbello presenting, “A Hauntological Manifesto for Book History,” at the panel Manifestos! co-organized with Beth Driscoll and Claire Squires, presented at annual meeting of the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing, Amsterdam, July 2022.

Strategic Factory. (2018). “8 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Envelopes,” https://strategicfactory.com/2018/11/8-things-you-probably-didnt-know-about-envelopes. Accessed January 30, 2023.