Author: Owen Clayton

Technocracy and T-Bone Slim’s Break with Ralph Chaplin

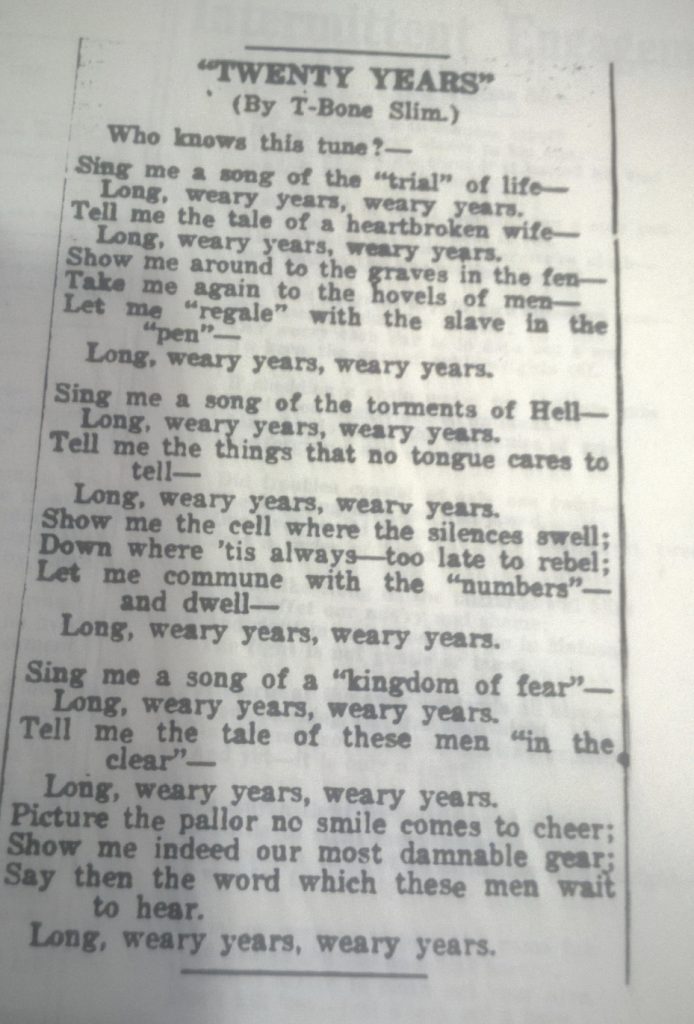

One of many mysteries in T-Bone Slim Studies is why he did not publish any new material for two and a half years, between Oct 1933 and April 1936.[1] However, in recent research trips to the Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan and the IWW Collection at Wayne State’s Walter P. Reuther Library, I think I have found the answer.

There is no central location of T-Bone Slim’s writings, scattered as they are in several different libraries and special collections. His complete works have never been collected and published. Indeed, such an undertaking would be very difficult since, as the T-Bone Slim and the transnational poetics of the migrant left in North America project has uncovered, the total number of his published pieces is over 1000. Getting an overview of his work is challenging, but the large number of articles he wrote also leads to a mystery of why he did not seem to publish any original material between Oct 1933 and April 1936.

The reason is that he had a personal and political falling out with Ralph Chaplin, the then-editor of Industrial Worker. Author of the famous song ‘Solidarity Forever’, as well someone who had gone to jail during the years of repression during and immediately after WWI, Chaplin was something of a literary giant not just for the Wobblies but on the American Left in general. He was a ‘Great Man’ within a movement that did not believe in Great Men.

Ralph Chaplin and Technocracy

Chaplin was also something of a political wanderer, someone whose politics shifted over time and meandered into some dark corners. By the early 1930s, he had become a devout follower of Technocracy, a movement that sought to replace political democracy with rule by experts, in particular scientists and engineers. In the US the Technocracy Movement was led by Howard Scott, and in Canada by, among others, Joshua Haldeman, Elon Musk’s grandfather (whose views shape Musk’s own projects in the 21st Century). In a Technocratic society, energy would be the default ‘currency’ (pun intended), with experts constantly monitoring how much energy individuals and organisations needed. In theory the amount of energy could be the same for all people, which made Technocracy appealing to some on the Left, like Chaplin. However, Technocracy’s status as an anti-capitalist or even ‘Left Wing’ movement was much contested, and today most scholars see it as a fascistic phenomenon.

Chaplin’s aim in taking over the editing of Industrial Worker was to make the paper more ‘professional’, which meant moving away from opinion pieces and towards more news coverage. Chaplin’s intention for this increased news coverage was, however, that it would be written from a hard-line party position, in effect making the paper less diverse and more propagandistic. His approach, which divided the IWW, meant that there would be less tolerance for the bizarre and sometimes politically-opaque writings of T-Bone Slim.

T-Bone Slim on Technocracy

In the period before Chaplin took over on 17th May 1932, Slim had been publishing regularly, sometimes having several pieces in a single issue. He wrote for the paper for 17 months during Chaplin’s editorship but tensions soon emerged. These tensions spilled out onto the pages of the Industrial Worker, but they did so in ways that were implicit rather than explicit. On 7th Feb 1933, Slim wrote an attack on ‘bosses’ and at the end sarcastically signed off as ‘T-bone Slim, Technocrat (Not connected with trust)’, the trust in question being Scott’s Technocracy Inc. If this was a dig at Chaplin, it was subtle. It is often difficult to work out the meaning of Slim’s sarcasm, but it does seem that tensions with his editor were rising.

For the 7th March 1933 issue, Chaplin seems to have requested pro-Technocracy articles from several of his writers, including Slim. While the other published pieces are straightforward peans to Technocracy, Slim’s article was different. He wrote: “it is almost unbelievable that an adding machine puts the essence of victory into Labors [sic] hands…along comes a set of mathematicians, impervious to all sentiment, and dissect the Industrial World in cold blood”. The quote drips with irony, even sarcasm, so that we might infer that it is indeed ‘unbelievable’ that Technocracy has solved the longstanding contradictions of capitalism. This kind of ironic prose was certainly not what the propagandistic Chaplin expected from his authors.

On the 4th April, Slim once again had technocracy in his sights, writing “A Technocrat is one who rubs elbows with work, is on speaking terms with it.” Given how derisive Wobblies were about managers who did not perform the work they expected from others, this is hardly a ringing endorsement! On the 4th July, he followed this up with: “Beware of practical men. They dream only of what can be, not of what should be.” While this quote is not definitely about Technocrats, I would argue that it is an attack on a movement led by ‘practical’ engineers and scientists such as Howard Scott.

Slim’s Fluctuating Writing Career

By October, Slim’s articles vanished. No other wobbly papers existed by this time and so he seems to have simply stopped publishing. A note held in the Reuther Library indicates that some writers who once appeared in the Industrial Worker were now staying away, as they no longer wished to appear in a paper edited by Ralph Chaplin. Slim seems to have been among this group. He does not appear in the paper again for two and a half years, notably returning within only three issues of Chaplin’s departure, once the Editorship had passed to Fred Thompson. His first article back, on 11th April 1936, attacks the concept of leadership, presumably with the ‘Great Man’ Chaplin in mind, and, once again, critiques those whom he calls ‘practical men’. By now the Wobblies had turned away from Technocracy and, over time, would come to see Chaplin as a troubling, even Right Wing figure.

Slim’s handwritten notes held in the Newberry Library, it seems to me, mostly date from the period just discussed. Indeed, some of the material in those notes would appear in the paper during the late 1930s under Thompson, who claims to have been given a stack of Slim’s earlier writings, almost certainly the Newberry notebooks. As research continues, we are beginning to see how different archives build up a more complete picture of the fluctuations of Slim’s career.

Notes:

[1] Slim had had publication gaps before, but this is by far the longest. Earlier gaps are often to do with illness or being away for work.