On the 13th of June Finland held municipal elections that were moved from April due to a worsening pandemic situation. This decision at the time caused criticism from some of the opposition parties, who claimed that Finnish democracy was threatened. In Russia, in turn, the next municipal elections will be held in a number of regions on the all-Russia voting day on the 19th of September amidst worsening repressions against the opposition. We decided to invite four experts from Finland and Russia to discuss these elections and what can be learned from both countries – Finland, an established democracy that enjoys one of the best in the world media freedom, and Russia, a peculiar authoritarian state where some local elections sometimes are pretty competitive.

Josefina Sipinen, who has just defended her doctoral dissertation about the recruitment of immigrant origin candidates in Finnish local elections at the University of Tampere, in her opening word talked about the harassment that municipal candidates face. especially women and representatives of ethnic minorities. Jesse Jääskeläinen, who ran as an SDP candidate at the Helsinki municipal election 2021 and served as a municipal councilor in Muurame (Central Finland) in 2017-2020, agreed with Sipinen. Jääskeläinen wondered whether there is an objective increase in hate speech or do the candidates just speak more openly about it. This issue maybe became more prominent this year also because the campaign was essentially moved online due to the pandemic.

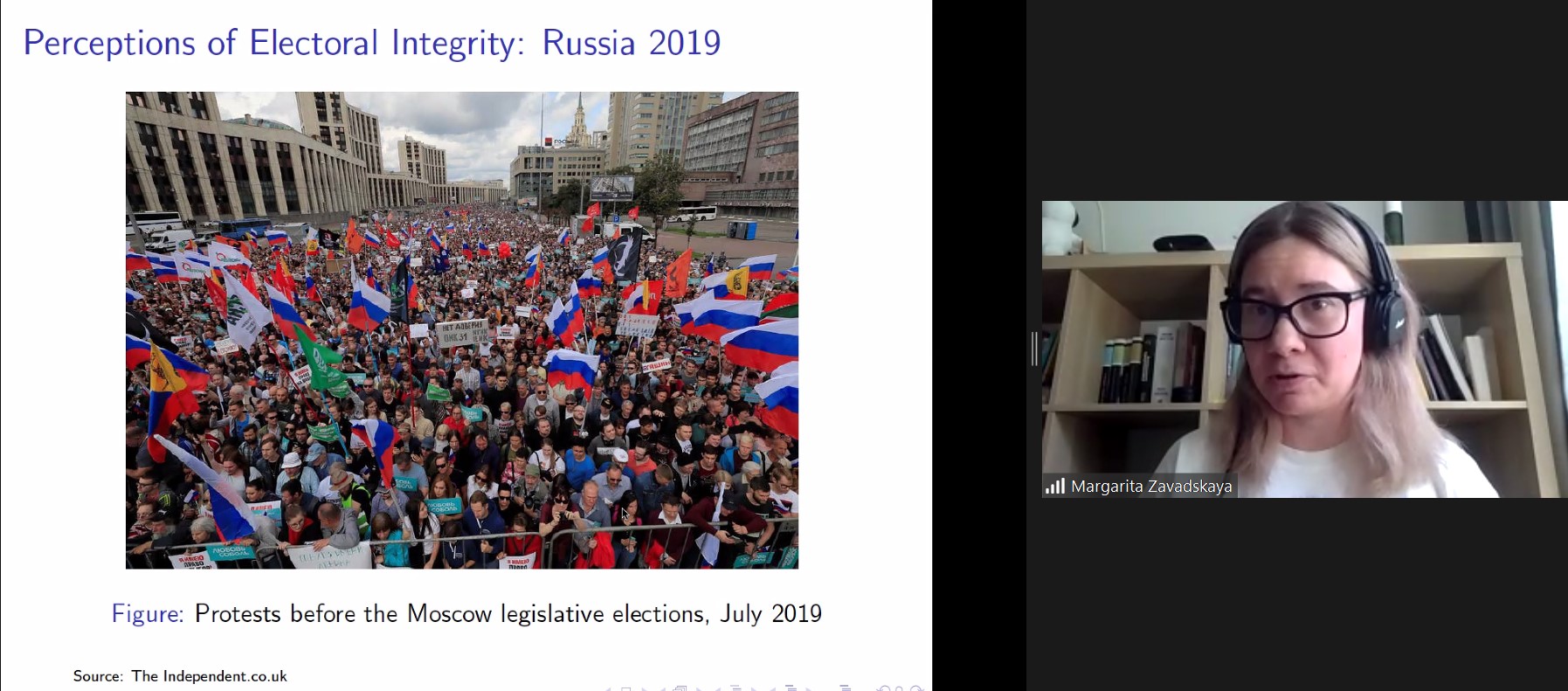

Speaking about local elections in Russia, Vsevolod Bederson, coordinator of “+1” electoral coalition at the Perm City Duma election 2021 and a PhD in Political Science, pointed out that running an opposition’s campaign in modern Russia is challenging, which is further exacerbated by the recent court decision that classified Navalny’s structures and their supporters as extremists and forbade them to take part in the elections. Anton Shirikov, who is a PhD Candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, studying propaganda, misinformation, and perceptions of media in post-Soviet states, spoke about the foreign interference and the use of misinformation in elections. Based on the collected by the EU data he showed, that the foreign interference in local elections is low, especially in Finland, and stressed that the danger of misinformation is not in the thing itself, but rather how local politicians decide to use it in their advantage.

A low turnout at municipal elections is a problem that is witnessed in both countries. In Finland, there is lower voting among young people, who might prefer others forms of political participation. Jesse Jääskeläinen noted that it is crucial for a young person to vote in their first-time elections in order to continue voting at the upcoming elections. This might be an issue for many children of Russian migrants in Finland. For Russian voters the role of the institutional heritage should also be taken into account: people are not used to political participation.

Low turnout in Finnish municipal elections among Russian speakers might be explained by the high heterogeneity of Russian speakers who live all over the country and are hardly reachable due to the geographical aspect. Moreover, it is challenging to run in the elections with a Russian background because of the language barrier and the need for an established network: in order to run from the party, a candidate should already have connections within parties and support within. Methods of the selection of candidates vary among parties and cities, bigger cities – tougher competition.

Talking about the important topics of this year, surprisingly the pandemic is not a central issue. However, in Finland, the blame attribution is visible among entrepreneurs and workers of the cultural sphere which is hit hard by the restrictions. While in Finland climate change is the most polarising topic at the local elections, in Russia the main rivalry happens between regime supporters and opposition, especially after the Anti-Corruption Foundation of Alexei Navalny was claimed as an extremist organization.

At the end of the discussion, the speakers talked about Voting advice applications or VAAs (vaalikone in Finnish). in Finland, older people and residents of the smaller towns rarely use Vaalikone since they often already know whom to support or are not familiar with new technologies. Candidates note that such instruments do not always focus on the local level issues, which is challenging for elections of municipal level. VAAs are mostly beneficial for the media which creates news from it. In Russia, VAAs are not in use, and if they were, it would harm the ‘Smart Voting’ strategy and split the opposition votes.

The full recording of the discussion is available below. It was a great exchange of experiences and ideas between the Russian and Finnish sides and we hope that it can inspire researchers and practitioners to look at the municipal elections from a new angle.

Regina Smyth is a Professor of Political Science at Indiana University. Her primary research interest is in the dynamics of state-society relations in transitional and electoral authoritarian regimes. She has also has written extensively on political development in the Russian Federation, including her recent book Elections, Protest, and Authoritarian Regime Stability: Russia 2008–2020 (Cambridge University Press, 2020). At the workshop, Professor Smyth will give a talk “Electoral Manipulation, Information, and the Path to Post-election Protest”:

Regina Smyth is a Professor of Political Science at Indiana University. Her primary research interest is in the dynamics of state-society relations in transitional and electoral authoritarian regimes. She has also has written extensively on political development in the Russian Federation, including her recent book Elections, Protest, and Authoritarian Regime Stability: Russia 2008–2020 (Cambridge University Press, 2020). At the workshop, Professor Smyth will give a talk “Electoral Manipulation, Information, and the Path to Post-election Protest”: