Kesän kenttätyömme herättivät huomiota sekä paikallisten keskuudessa että tiedotusvälineissä (esim. Sompio-lehti, Barents Observer). Tällä kertaa olimme tähän hieman paremmin valmistautuneita kuin aiemmin. Vuonna 2007, kun aloitimme toisen maailmansodan kohteisiin liittyvät tutkimukset Lapissa, saimme ensimmäiset vihjeet aiheen nauttimasta mielenkiinnosta, ja tutkimuksista julkaistiin useita meidän ja muiden kirjoittamia artikkeleita paikallisissa sanomalehdissä.

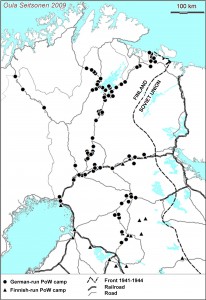

Kun aloitimme toisen maailmansodan kohteiden kaivaukset vuonna 2009 saksalaisten tukikohdassa ja vankileirillä Inarin Peltojoella, olimme kuitenkin ällistyneitä tutkimusten osalleen keräämästä huomiosta. Toisen maailmansodan kohteita oli tutkittu aiemmin Suomessa hyvin vähän ja kaivausten herättämä kiinnostus yllätti meidät täysin, kun eri televisiokanavien ja sanomalehtien toimittajat sekä paikalliset vierailijat alkoivat piipahdella paikalle seuraamaan kenttätöitämme.

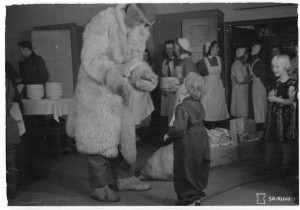

Osaltaan tämä julkinen kiinnostus ja eri ihmisten aihetta kohtaan osoittamat kiihkeät tuntemukset ja mielipiteet innostivat meidät aloittamaan nykyisen tutkimusprojektimme suunnittelun. Sen vaikutuksesta kiinnostus suuntautui tarkemmin siihen miten eri yhteisöt ja ihmisryhmät, kuten paikalliset asukkaat, sotahistoriaharrastajat tai metallinilmaisinharrastajat, ovat suhtautuneet ja suhtautuvat kohteisiin. Vuoden 2009 tutkimusten myötä Oulaa pyydettiin myös avustamaan asiantuntijana kahdessa dokumenttiprojektissa: venäläisistä sotavangeista kertovan “Jäämarssi”-dokumenttielokuvan valmistelussa ja “Suojele minua”-sarjan jaksossa, jossa tutustuttiin Inarin Nangujärven alueen saksalaisten vankileireihin.

Joku sotahistoriaharrastaja on ladannut Youtubeen kaksi uutisfilmiä vuoden 2009 kaivauksista (tekijänoikeuksista välittämättä…):

https://youtu.be/VqRP6wYgc5I?list=PL0CFDA33427210464

https://youtu.be/_REoa-OAzlw?list=PL0CFDA33427210464

Aki Romakkaniemi Inarin Nangujärven eteläpään vankileirillä, taustalla hyvin säilynyt saksalaisten hirsirakennus / Aki Romakkaniemi at the German-run PoW camp at Inari Nangujärvi, a well preserved German WW2 log cabin on the background (Kuva: http://yle.fi/vintti/yle.fi/teema/sites/teema.yle.fi/files/nangujarvi_ehdotus.jpg).

Aki Romakkaniemi Inarin Nangujärven eteläpään vankileirillä, taustalla hyvin säilynyt saksalaisten hirsirakennus / Aki Romakkaniemi at the German-run PoW camp at Inari Nangujärvi, a well preserved German WW2 log cabin on the background (Kuva: http://yle.fi/vintti/yle.fi/teema/sites/teema.yle.fi/files/nangujarvi_ehdotus.jpg).

Our summer’s fieldwork raised interest both amongst the local public and media in our study areas (e.g. Sompio-lehti, Barents Observer). This time we were little more prepared for this than earlier. Back in 2007 when we started research on World War 2 (WW2) sites in Lapland, we got our first glimpses of the public attention to this subject, which resulted e.g. in articles in local newspapers by us and others.

However, we were amazed of the public interest when we launched the excavations of Lapland’s WW2 installments in 2009, at the German-run military base and prisoner-of-war camp at Peltojoki, Inari. WW2 sites had been studied in Finland only occasionally before that and the public and media interest our studies got both during and after the fieldwork completely surprised us, when the different TV channels and newspapers started sending their reporters out to the site and frequent visitors dropped by to observe fieldwork.

In part it was this public interest and people’s passionate feelings towards and opinions of the WW2-era sites in Lapland, which initiated the planning of our current project, and got us to inquire more closely how the various communities, such as local residents, war history buffs, or metal detectors, have signified and engaged with those sites. As a follow-up to our 2009 excavations Oula was asked to take part as a specialist in some documentary projects: the preparation of documentary film “Jäämarssi” about Russian PoWs and an episode of the “Suojele minua” (Eng. Protect me, a series about preserving Finland’s built heritage) documentary series dealing with the German PoW camps in Inari Nangujärvi.

Some war history enthusiast has also uploaded two of the news clips from 2009 excavations on Youtube (probably a copyright violation…):

https://youtu.be/VqRP6wYgc5I?list=PL0CFDA33427210464

https://youtu.be/_REoa-OAzlw?list=PL0CFDA33427210464