Author: Saku Pinta

T-Bone Slim’s Forgotten Finnish-Language Writings in the IWW Press

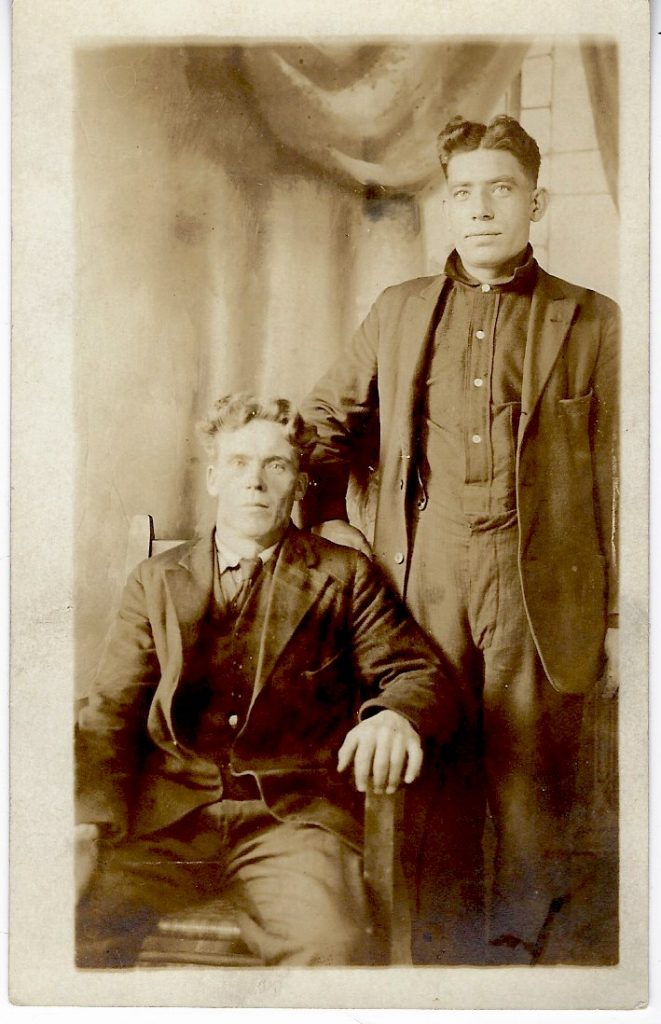

Many new discoveries have been uncovered as the T-Bone Slim and the transnational poetics of the migrant left in North America research project has progressed over the last ten months. These discoveries have helped to shed considerable light not only on Slim’s life but also on his relationship to the Finnish-language and to Finnish immigrant communities in North America.

Last month, for instance, project research assistant Lotta Leiwo announced the discovery of a Finnish-language text written by Slim in 1903, using the pseudonym Mathew Houghton, during his time as a participant in the Finnish immigrant temperance movement.

This discovery shows that Slim had a much higher level of Finnish-language fluency than previously assumed. Until very recently, Fred Thompson – formerly the editor of the Industrial Worker newspaper as well as an instructor and director of the Work People’s College, among his many other roles in the IWW – had been the main source of information on the topic of T-Bone Slim’s ability to communicate in the Finnish-language.

T-Bone Slim’s Finnish Writing: The Evidence

This comes from one little snippet from an interview conducted by Franklin Rosemont with Thompson – who personally knew Slim – which appeared in the introduction to Rosemont’s edited volume Juice is Stranger than Friction: Selected Writings of T-Bone Slim. In the interview, Thompson says “I doubt whether T-Bone was familiar enough in Finnish to be funny…though he could speak it.” As a non-Finnish speaker, Thompson could only modestly doubt, rather than completely rule out, Slim’s ability to communicate effectively enough in Finnish to be funny.

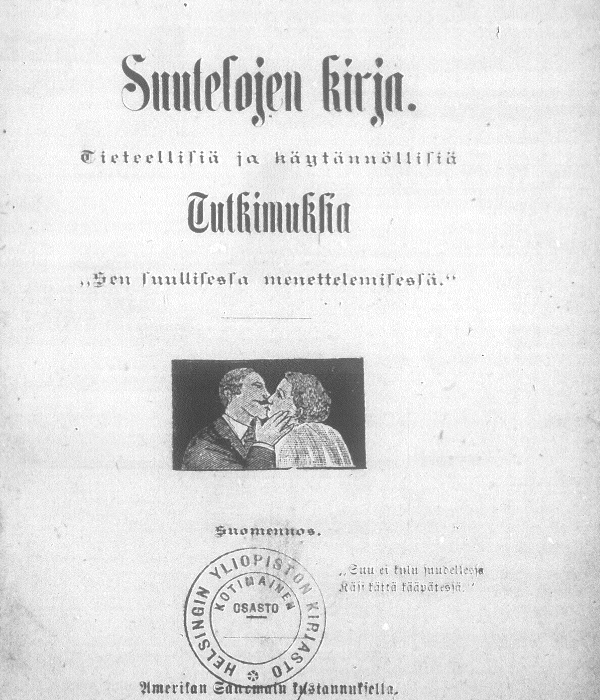

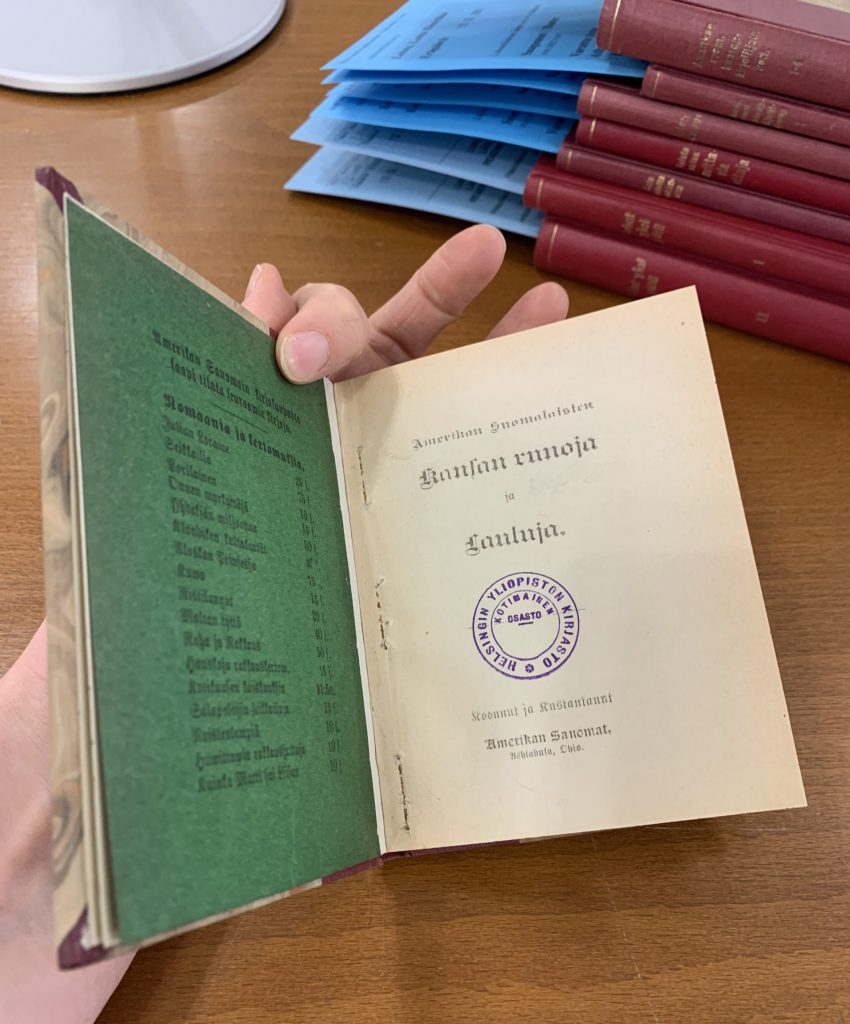

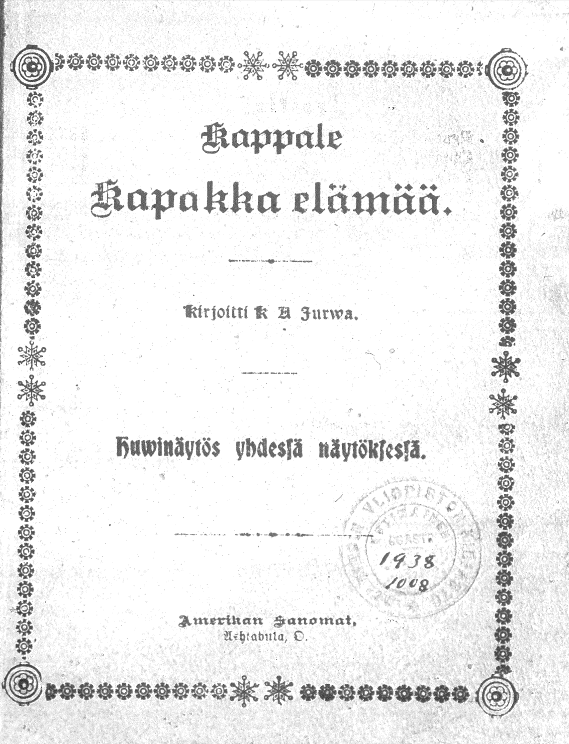

However, we now have compelling evidence that suggests that Slim wrote for the Finnish- language IWW press in the early 1920s. As many as three Finnish-language writings by T- Bone Slim have been uncovered, but there may be more. This blog post will focus on one of these texts – the earliest confirmed Finnish-language writing by T-Bone Slim, or at least the earliest one uncovered so far.

It is a short piece entitled “Joitakin Terveysopillisia Neuvoja” (Some Hygienics Advice) which appeared in the August 27, 1922 issue of the Duluth, Minnesota-based Finnish IWW newspaper Industrialisti.

The English-language translation is as follows:

Some Hygienics Advice

By T-Bone SlimExercise for fifteen minutes in the morning, and the same amount in the evening. Do it when the boss is watching.

Use as much oxygen as possible. Sit down and breathe deeply occasionally. Nobody will care about that – they will think you are sighing. [Note: in the original Slim says “happoa” or acid, instead of “happea” or oxygen. This may be a typo or it might be that Slim accidentally used the wrong Finnish word – albeit one that was similar to the intended word – which was then reproduced in the newspaper.]

Never unbutton after eating – buy looser fitting clothes. Sleep sixteen hours a day in an airy room.

Don’t try to lift too much. There are over 6,000,000 unemployed, who are very willing to “give a hand” and also – you can tear something.

Don’t eat hastily (A horse is given an hour and fifteen minutes to eat).

Don’t go to work early. “Organization in everything.” Your employer might soon say that you are showing too much affection for the workplace – which is “theirs.”

Read I.W.W. literature, in order to be able to say something.

T-Bone Slim’s Finnish Writing: Some Conclusions

How do we know that this is a text originally written in Finnish?

Again, no English-language version of this short piece has been found (although there is one text with similarities, which will be discussed below). Also, unlike most of the Finnish-language translations of Slim’s writings that appeared in Industrialisti in the 1920s, of which there are several examples, this one did not include the short introduction from the translator. These short intros by a translator would became standard feature, apologetically noting that much of Slim’s wordplay is nearly impossible to render into Finnish from English, and has thus been lost in translation. Finally, the possible accidental use of the word “happoa” instead of “happea” as well as the use of a fairly well-known, old Finnish idiom in quotation marks also suggest that this was originally written in Finnish. The idiom in question is “Järjestelmällisyyttä kaikessa”, translated above as “Organization in everything,” which could also be rendered in English as “systemitization in everything” or “be methodical in everything”.

Those familiar with T-Bone Slim’s writings will notice similarities between “Some Hygienics Advice” and “Recipes for Health,” published about a year later in 1923 in the pamphlet Starving Amidst Too Much. Aside from being similarly structured as a series of eight, short pieces of advice for workers, these two pieces also discuss things like the importance of an airy room for sleeping as well as cautioning against being in a rush.

While Slim’s hygienics advice may have served as a kind of template or first draft of his “Recipes for Health,” there is a notable difference. “Some Hygienics Advice” uses humour and hyperbole to emphasize the fact that workers and bosses have different interests. The main lesson is that workers should not eagerly participate in their own exploitation. Rather, slowing down at work can, for example, serve to reclaim some dignity (even a horse is given more time to eat than a worker) or convince the boss to hire more people and thereby reduce unemployment (working faster, or working overtime, as the old union saying goes, is scabbing on the unemployed). “Recipes for Health”, by contrast, uses a much more serious and forthright tone throughout.

There is much more work to be done around Slim’s Finnish-language writings and the many questions that they raise. But one thing is certain: the satisfaction of uncovering these lost writings by T-Bone Slim is only matched by the satisfaction of making them available to a wider readership. We very much look forward to finding and sharing the next discovery.

![Man performing on a stage with a guitar. Plants and flowers, three persons playing and singing in the background.]](https://blogs.helsinki.fi/tboneslim/files/2022/08/John-performing-at-Valkeakoski-workers-music-festival-2022.jpg)