Author: John Westmoreland

“Weary Years”: A Retrospective 101 Years Later

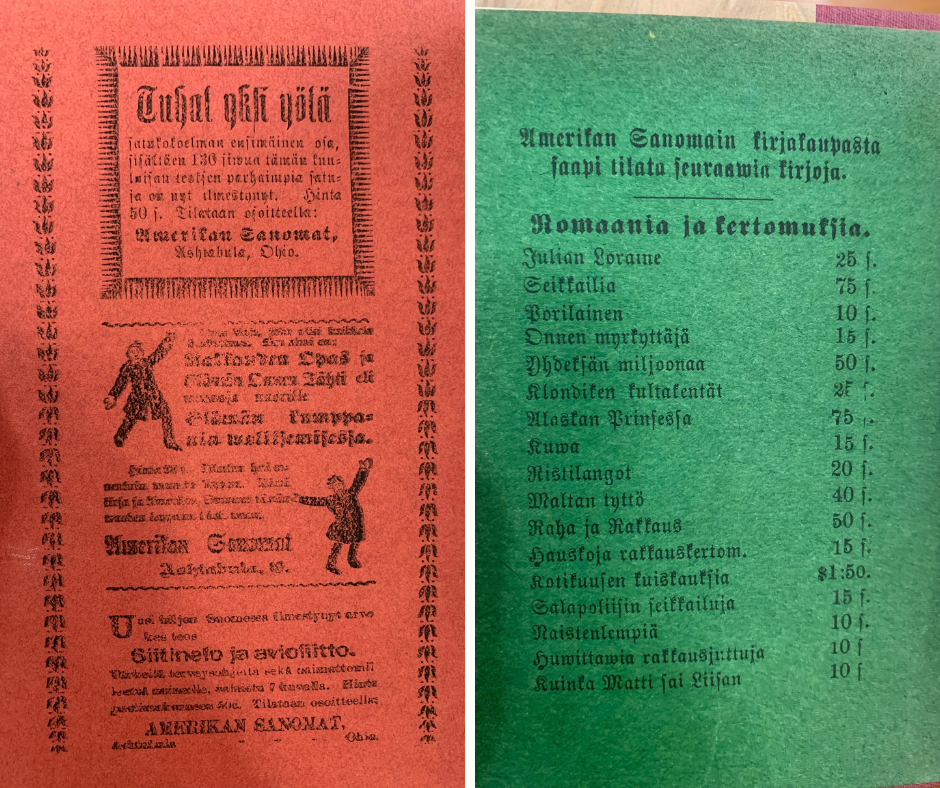

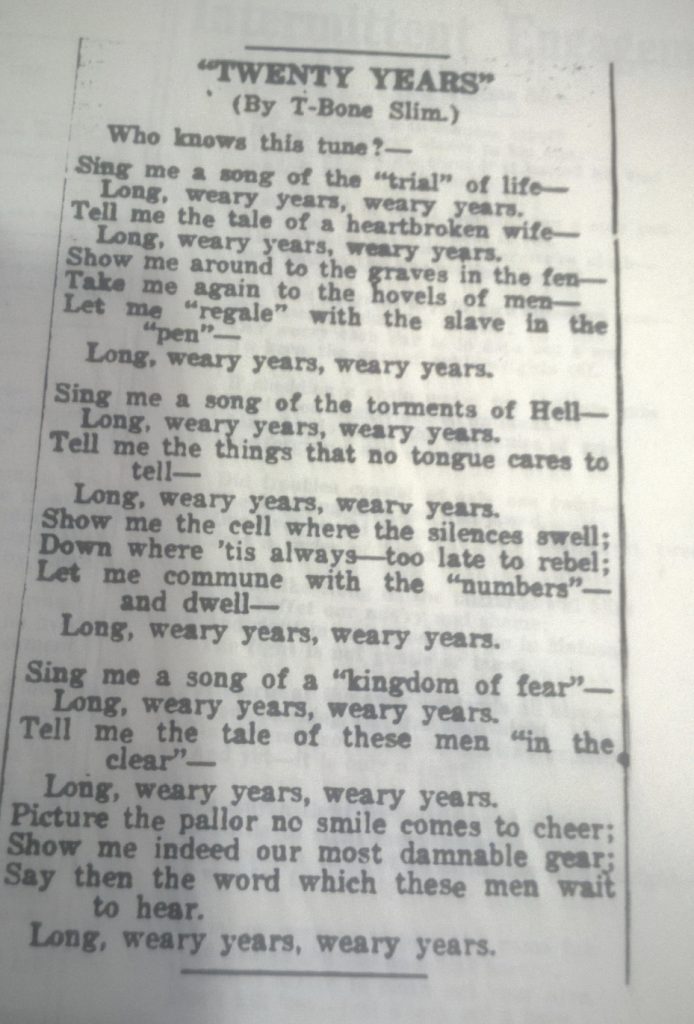

On June 11th, 1921, exactly 101 years ago, a song appeared in the pages of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) periodical, the Industrial Worker, titled “Twenty Years”. It was credited to T-Bone Slim, and as of this writing, represents the earliest known publication of his work in the IWW’s flagship newspaper.

Unlike the majority of T-Bone Slim’s songs-and indeed the vast majority of those found in the IWW’s infamous Little Red Songbook—it doesn’t appear to be based on any popular tune, or traditional melody from the past, as had been common practice among songwriters such as Joe Hill, the IWW martyr who penned classic labor anthems like “The Preacher and the Slave” and “There Is Power in a Union”.

The idea of using well established melodies—be they religious hymns, revolutionary or civil war era songs, or contemporary hits of the day—and rewriting the lyrics, with an infusion of irony, sarcasm, and revolutionary sentiment, allowed IWW songwriters to breathe new life and spirit into music that was already deeply ingrained into the consciousness of western industrialized society.These new lyrics often flipped the script on the original song’s meaning and implored the working class to rise up collectively against the shackles of the capitalist system and the “industrial overlords” ruling it.

One significant benefit of this songwriting practice was that rank-and-file IWW members, who might not have any formal music training, could pick up a copy of the Little Red Songbook and easily begin singing together as a group. The songs were published using their new titles and printed beneath would be the name of the original melody in parentheses.

However, in the case of T-Bone Slim’s “Twenty Years” (Or “Weary Years” as I’ve taken to calling it) there is no subheading pointing to a previously written melody. Instead, beneath the title, there is only a question to the reader, “Who knows this tune?”

“Weary Years” Today

Putting that question aside for the moment, let’s have a listen to the song. This recording and video marks its first known release—exactly 101 years to the day after the lyrics were published on June 11, 1921.

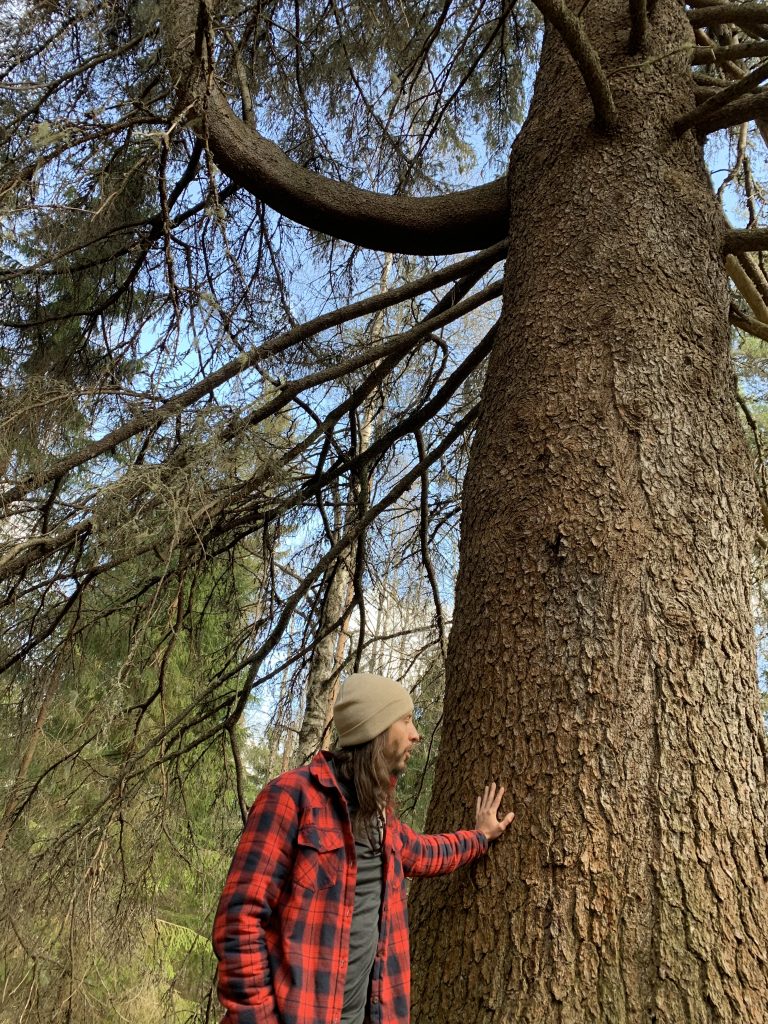

I must say that it’s been a truly unique and deeply meaningful experience for me to have the opportunity to collaborate with my long forgotten great granduncle; composing and arranging music to accompany the words he wrote over a century ago… And I’m sincerely grateful to the musicians, sound engineers, videographers, and artists who contributed to this work in the US and Finland, and to fellow T-Bone Slim researcher, Dr. Owen Clayton, who brought this song to my attention in 2018. “Weary Years” is one of 9 songs comprising a new, full album of T-Bone Slim’s songs and poems, Resurrection.

Trial of Life to Trail of Life

So why did T-Bone Slim choose the title “Twenty Years”? What is he referring to? Well, it’s certainly up for debate, but perhaps one important clue lies in the first verse. Astute listeners and readers may notice a discrepancy between the original published phrase “Trial of life” and what I sang on the modern recording, “trail of life”. Admittedly, this was not a conscious decision on my part, but seeing as I’ve been on the “trail” of T-Bone Slim for quite a while, I hope Uncle Matt forgives me for the artistic indulgence. In any case, what “Trial” might he be referring to? T-Bone Slim researcher, Dr. Saku Pinta, has a good theory about this. It involves the massive show trial against IWW leaders during the first half of 1918…

Since its founding in 1905, the IWW’s numbers and influence had grown significantly over the years. As their organization and effectiveness increased, they also found themselves evermore in the cross hairs of government and corporate powers. This came to a head most brutally during the period of the first World War.

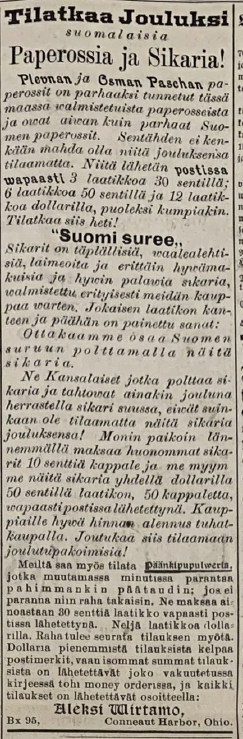

Because of their uncompromising antiwar stance and their successful efforts to organize in key war time industries such as copper mining and lumber, the IWW, or “Wobblies” were viewed as Enemy No.1 by the Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Justice Department, and the aptly named, War Department.

On September 5th, 1917, just months after the US entered into the worldwide conflagration, and Congress had passed the draconian Espionage Act, the Bureau of Investigation undertook an unprecedented operation. In the span of 24 hours, they raided every IWW office across the country, in what may well be the widest ranging search warrant ever executed in US history. Ultimately, the Justice Department would go on to successfully prosecute one hundred and one IWW leaders. After a months long trial, all of them were found guilty in less than one hour of jury deliberation, and fifteen received the maximum sentence, “Twenty Years” in prison…

The Espionage Act was brought into existence and first implemented as a means to brutally attack and cripple the IWW, but today it continues to be wielded against modern dissidents, whistle blowers, and publishers, in particular those who expose US war crimes.

If T-Bone Slim were to write the song today, perhaps he would title it “One Hundred and Seventy Five Years”.

—“Who knows this tune?”