We continue with our special coronavirus series “Politics & Pandemics”, and this week’s post is written by ElMaRB project leader Dr. Margarita Zavadskaya. In the series, we provide weekly updates on the coronavirus outbreak and its effects on politics, media, and activism. We will publish blog entries written by us and invited experts, where we will try to look at the current events through the prism of political and social sciences.

Reading time: 5 minutes

The COVID-19 has reached Russia. As of April 9, the number of confirmed coronavirus patients amounts to 10131 in 81 regions with 1459 new corona-positive cases. The head of the Medical and Biological Agency (FMBA) and Veronika Skvortsova expects the epidemic to peak in late April. The outbreak of the disease seems to spread faster in Russia and in a more uncontrolled manner despite a number of severe quarantine restrictions implemented recently – fully sealed borders with tens thousands of tourists remaining outside, web cameras, specialized smartphone apps and QR-codes detecting violators of mandatory quarantine and tracking people’s movements in Moscow. There is little doubt that the consequences of the epidemic will not only overload the capacity of the Russian healthcare system, but will lead to a protracted economic recession in the country, the collapse of the business, especially services and retail, and considerable rise of unemployment.

Less than a month ago, Russian authorities tried to play it cool by ‘ridiculing’ the panicking West on TV and pushing forward an all-Russian vote over the constitutional amendments that would extend V. Putin’s legal terms in power. The very nature forced President V. Putin and his administration towards two decisions: to postpone the vote on the constitutional amendments and to give three national addresses to make the best of a bad job. It is likely that the postponement of the ‘constitutional’ vote will downplay the Kremlin’s mobilization efforts and rip away the symbolic value of the whole enterprise. However, it does not mean that voters will not show up, it rather means that the state will have to rely on a forced mobilization more intensely.

Exogenous shocks affect political support differently conditional to the nature of the challenge. During the wildfires crisis of the hot summer in 2010, scholars observed systematically higher political support in the settlements of Central Russia engulfed in flames compared to those bypassed by the fire (see Lazarev et al. 2014). The reason is that citizens directly observe the state in action and do not attribute the blame to the authorities. Scientists came to the similar conclusion studying the consequences of Hurricane Katrina in the US or river floods in Leipzig, Germany (Bechtel and Hainmueller 2011). The bottom line, if natural disasters normally boost political support, economic crises kill it (Healy and Malhotra 2013). The latter usually translate into massive discontent with the incumbent governments almost everywhere. For instance, most of the national governments resigned after the outbreak of the Great Recession in 2008-9 no matter their ‘colors’ (Armingeon and Ceka 2014).

According to the independent Levada Center surveys, respondents’ concerns regarding the virus seem to grow slower than fears of inflations and deterioration of current living standards. Some experts like Alexander Kynev expect dramatic erosion of popular support of the current political regime:

The second ‘coronavirus’ address by the president whose content boils down to three points (two openly announced points – a month extension of ‘the quasi-quarantine’ and shifting all the decisions to the governors, and one point that remained unsaid – no state assistance for the citizens and business) seems to be – to say at least – a major blunder from all possible angles. This is a mistake from the viewpoint of maintaining an image of a strong leader in the eyes of the population, if the ultimate goal is upholding popular support. This is a mistake in the eyes of the (any) business, if the goal is to keep the latter on the regime’s side. (…) Creeping empowerment and bureaucratic decentralization coupled with the center’s self-withdrawal from decision-making look unavoidable.

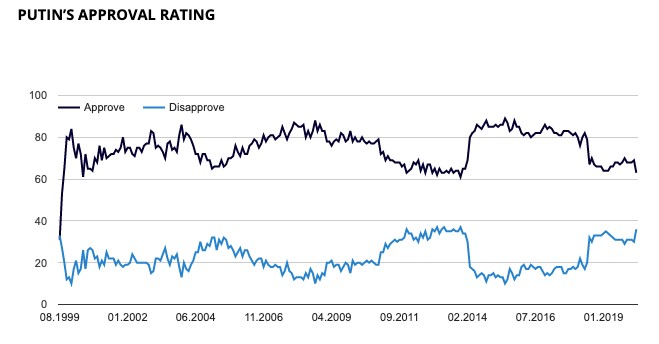

Russian polls have produced ambiguous results. Levada Center reports that the president’s support has declined by 6% from 69% in February to 63% in March, and there are grounds to expect further decreases. At the same time, the state-controlled polling agency VCIOM asserts that Putin’s rating has risen after the first two presidential addresses (74%). Although these data are not publicly available and the Kremlin decides what data are released. Another pollster, FOM confirms the short-term positive dynamics and explains it by the rallying effect against the common threat. Similarly, the post-Crimean recession in fall 2014 did not result in any decline in support because of the patriotic rallying and the fact that most Russians attributed political blame to external political forces and international sanctions imposed by the West (Frye 2019; Sirotkina and Zavadskaya 2020). This time the blame is very likely to be attributed to the executive power together with the president. The downward trend has already started in summer 2018 after the announcement of the unpopular pension reform.

These dubious polling results can be easily explained by two mechanisms: 1) popular disappointment may replace a short-term rallying effect reported by polling agencies, and 2) Russian respondents differ in the way they attribute political blame: the president is mostly held accountable for international affairs, while the government is in charge of domestic politics (although, blaming depends primarily on citizens’ political views: oppositionists punish the president first, while supporters tend to blame the State Duma and the government). So far, the Kremlin strives to delegate unpopular decisions to the government and its agencies and governors who do not enjoy any leeway here. As professor Vladimir Gel’man warns, such attempts may come at greater costs for the governability and state capacity:

Russian regime (and not only Russian) depends on visible mass support and rightly fears that exogenous shock may (but not always) trigger a mass demand for regime change. Here comes the strive to shift the blame for unpopular measures from the president to the government and regional heads. But to play in ‘good cop vs. bad cop’ seems to be a bad idea as an uncontrolled decentralization of ‘the overregulated state’ (a term by Ella Paneyakh) would just make the situation worse…

On one hand, personalist authoritarian regimes usually sustain themselves for a fairly long time even under a crumbling economy and lingering recession. On the other, the speedy character of the unfolding crisis can trigger more dramatic consequences not just for the government and some officials, but the regime as a whole. One way or another, the upcoming vote on the constitutional amendments will take place under the circumstances that are completely unforeseen by the Kremlin.