During the last months, we observe a dramatic variety of how countries with diverging healthcare systems and regimes react to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to several accounts, the Chinese coping model of containing the disease seems to provoke a lot of interest if not admiration. However, China is infamously known for systemic misreporting on the state of affairs and this experience should be taken with caution. Communist and post-communist states share the common legacy of a universalistic welfare system based on political compliance (putting aside special services for the privileged groups) (Cook 2011) and it is the case of former-USSR states. Today we are glad to publish a short analytical entry by Mirzokhid Karshiev, Doctoral Candidate in the Global Processes and Flows in the Eurasian Space research group, with an insider’s view on how Uzbekistan – another example of a closed state with communist legacy – manages the challenges of COVID-19. Mirzokhid Karshiev is currently conducting fieldwork in Tashkent in the H2020 MSC RISE project New Markets.

Reading time: 13 minutes

Many residents of Uzbekistan will probably for a long time remember the day when the first person with a new COVID-19 infection in the country was publicly announced because it was immediately followed by very drastic measures on social distancing.

On 15 March 2020, I was in a southern city of Karshi, in a public park, where hundreds of people assembled to celebrate the traditional Navruz holidays. All of a sudden, the organizers canceled the event and told the public to go back to their homes. The news that people were following on the screens of their TVs and phones about a virus outbreak in China, later on in Italy and Spain, suddenly became a reality.

At a press conference on that day, the country’s Prime Minister Abdulla Aripov informed that from 16 March all schools, kindergartens, and higher educational institutions would be closed for quarantine, all international air, road and rail passenger transportation canceled (from 19 March), as well as all sports competitions, cinemas, theatres, and other public events. The Government reported that around 80,000 students were sent back from Tashkent to the regions on these days on organized transport.

“From now on, all people, who will be arriving from other countries will be subject to mandatory two-week quarantine in the facilities, chosen by the government”, said the Prime Minister. Those, who have arrived in the country at the beginning of March, including a fellow researcher from the University of Rotterdam, also reported that they were placed under home quarantine post-factum.

A taxi driver, who drove me two days later from Dehqonobod district in Kashkadarya region to Denov district in Surkhandarya, told me that shared taxi (a popular mode of public transport in the country) fares from Tashkent to the regions tripled those days because of a mass exodus of students. I hoped that most of the travelers didn’t have to pay these hefty prices, but could use cheap and sometimes free transportation, hastily arranged both by the authorities and ordinary people.

That driver was driving home to a border district of Sariosiyo from Samarkand, where he worked at a local bazaar, selling vegetables and fruits, to see his ailing mother. At the time, he was quite optimistic that a virus will go away with the coming heat and happy that he could sell all his potatoes in a day, which in normal times would take a week. I don’t know if he was able to go back to Samarkand, as days later, social distancing measures started to increase in cities: Tashkent and regional centers have soon closed down for entrance and exit for ordinary people, all flights, inter-city trains, and buses, as well as public transportation within cities, have been stopped. From March 22, the people were required to have face masks when they were outside home, even in their cars and faced a hefty fine for breaking the new rules.

With numbers of detected coronavirus transmissions increasing, the restrictive measures were strengthened. Starting from 30 March, private cars, passenger vans and motorcycles have been banned from the streets in Tashkent and other regional centers, with only a selected list of governmental cars, as well as those, who have obtained special permission, allowed.

On 13 April, after six cases of community transmissions of the virus were reported in Namangan city, the local government imposed measures very similar to the ones in Wuhan, ordering everyone to stay at home, allowing a single person from each household to leave the house per day to a nearby (up to 100 meters) supermarket/shop to buy food and other essentials.

The restrictive measures have had an effect. According to the self-isolation index, developed by Yandex, which uses data it collects through different web-services, Uzbekistan’s cities have shown far more isolation than other CIS countries. Below you could see how self-isolation levels in Tashkent have changed starting from 23 February to 13 April.

Figure 1. The Dynamics of the Self-isolation Index (Yandex) in Tashkent, Uzbekistan; April 13, 2020. The green (4-5 pts) stands for high self-isolation (no people on the streets), the orange and yellow – 2.5-3.9 pts (few people on the streets), and the red – 0-2.4 pts – a lot of people on the streets.

Source: Yandex

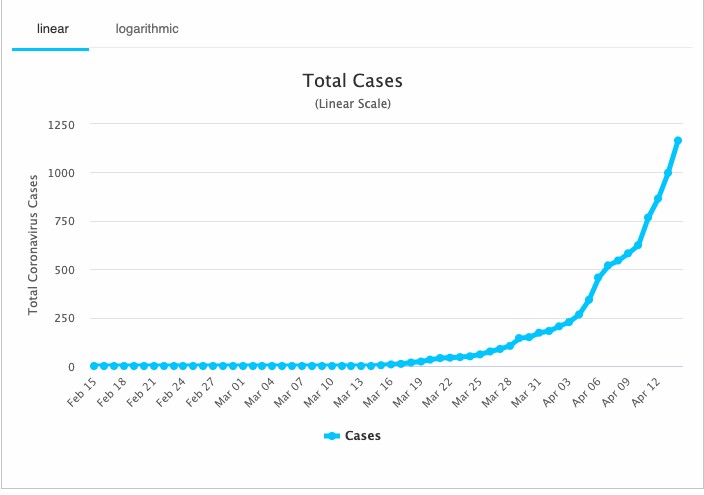

As of 15 April, the total number of COVID-19 cases in the country stands at 1275, with 99 recovered and 4 deaths.

Figure 2. Total Coronavirus Cases in Uzbekistan.

Source: Worldometers.info

Decision-making practices

President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, a son of a doctor-phthisiologist, has won plaudits for his actions during the pandemic from both national and international media. He has been quite active, frequently chairing governmental meetings on different issues as well as conducting telephone conversations with the leaders of neighboring countries, offering help and discussing joint coordination.

While most of Uzbekistan’s residents have supported the swiftness and early introduction of social distancing and self-isolation policies, some criticized the government’s habit of last-minute decisions, causing anxiety and the sense of urgency among the population. Some of these decisions seem not to have taken into account different life situations. My mother, who works in a local clinic in Chirchiq, currently has to depend on her colleagues to drive her to and from work or walk a 3 km. distance one way.

Most of the decisions on lockdown measures have been made by the special republican commission on preventing entry and dissemination of a new coronavirus in Uzbekistan, established on 29 January 2020 with a Presidential resolution, however, the full texts of these decisions haven’t been made available. Answering the questions in this regard, head of the state inspection for sanitary-epidemiological control N.Atabekov implied that the relevant parts of these decisions were being publicised through the websites of the Ministry of Public Health and the inspection, and other communication channels. Furthermore, the questions remain over the details of the delegation of the decision-making powers to the commission, as the resolution from January envisages commission will only prepare recommendations to the President.

The centralised decision-making system in the country allowed rapid lockdown, however, the different epidemiological situations in various parts of the country, requires local governments to take more decisions on their own, which might prove a challenge.

Mobilized state

Researchers have frequently noted the mobilization techniques the state in Uzbekistan used in the past to kickstart big infrastructure projects, to organize cotton and grain harvesting, overcome economic difficulties. While in the last 4 years, there was more talk of using incentives and rule-based governance, the COVID-19 situation prompted a vast mobilization effort by the government. Enormous human and financial resources have been mobilized towards the construction of two hospitals for COVID-19 patients for 10,000 patients, as well as a big quarantine zone for another 20,000 people in the outskirts of Tashkent, some of which were completed in just over two weeks.

The sanatoriums, a legacy of the communist past, have proved to be useful for the pandemics. Tens of thousands of people, mostly arriving from foreign countries, were placed for 14-day quarantine in those sanatoriums all over the country, which have been hastily converted into isolation units. There have been reports in the social media that not all protocols have been complied with in some of them, resulting in virus transmissions. While the state media have not bothered to investigate this further, the President in one of the meetings criticised an unprofessional approach in the sanatorium in Bukhara, where a contact tracing map shows a surge in the number of cases.

Local government officials together with the tax office staff were sent to local bazaars to ensure price stability for essential foodstuff. The personnel from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the National Guard and even the Armed Forces have been dispatched around the country to control and limit people’s non-essential trips out of home. With schools closed indefinitely, the Ministry of Public Education took over the lot of several TV channels, preparing and broadcasting video lectures in Uzbek and Russian for schoolchildren all over the country.

Economic concerns

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the Uzbek government, as well as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, projected a growth rate of 5,5% for 2020. While the Government has not reported its new projections yet, most of the economic commentators are questioning if growth is possible. The World Bank and IMF baseline models project the growth will slow down to 1,6 and 1,8% respectively. It seems a big portion of the population might be very hard hit by the global lockdown measures. The Central Bank reported that remittances from foreign countries have been down by 23% in March compared to February 2020, on the first 8 working days of April contracted by 3 times in comparison to March. The Ministry of Employment of Uzbekistan estimates that there are around 2,6 million labour migrants in foreign countries, which roughly makes up 14% of the working-age population or 19% of the labour force. The Center for Economic Research and Reform, a government-affiliated think-tank, estimates that approximately 45% of the labour force is informally employed, most of whom depend on the daily income for their livelihoods.

Challenges ahead?

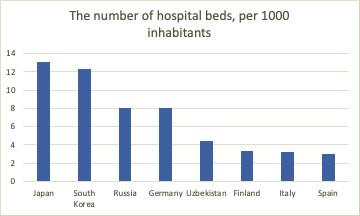

According to official statistics, Uzbekistan might be better prepared for the pandemic than many other countries. It had on average 153,6 hospital beds in total or 4,66 hospital beds per 1000 people at the end of 2018, which is significantly lower than in Germany, South Korea, Japan, and Russia, but 50% more than in Spain. There is over 500,000 medical staff, working currently in the public and private healthcare sector.

Figure 3. The number of hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants.

Source: OECD, State Statistics Committee of Uzbekistan.

However, the government has not clarified the number of intensive care units in the hospitals and the number of ventilators available for the healthcare sector. In one of the meetings on the COVID-19 situation in the country, the President of Uzbekistan informed that 500 ventilators have been ordered from Russia in March and they will be made available as soon as possible. There is a concern to what degree local medical staff is acquainted with and operate the new equipment or in general, can cope with increased pressure if the number of infections continues to rise. While social media was full of praise and support for healthcare professionals, many people have also voiced their deep concerns on the current state of medical healthcare in the country.

In demographic terms, the ratio of those over 70 years old (2,6%), is lower than in most developed countries. Most of the elderly people live with their children, an average household having three or more generations. Actually, living in a nursing home or away from children is considered to be the fate of losers.

Most of the population, especially in rural areas, live in close-knit communities (mahalla), where very close social interactions even among distant relatives, neighbors and sometimes strangers are a norm rather than an exclusion. An average wedding party gathers around 300-500 people, which the Senate of the country has lowered to 200 from the beginning of this year. Throughout history, the to’y (wedding or circumcision party), a quintessential part of the Uzbek society, has been very resilient. As an American anthropologist Russell Zanca put it: “Financial burdens aside, to’y must go on!”. With different forms of social distancing measures, projected to stay for this year, for anthropologists and other social scientists it would be interesting to see how the institution of “to’y” will evolve.

In urban areas, social distancing measures could be complicated through increasing urban densification processes (in Russian – уплотнение) in Tashkent and increasingly other regional centers, as more and more public space in and around residential quarters have been allocated for the construction of new houses in recent years.

Consequently, it might seem that harsh social distancing measures could be a proper response, but there is a strong pressure for the government to slowly open for economic activity. In an early hint of what’s to come, this week local governments started talking to local business people on the gradual opening of construction and production sites. Until now, the government has been strictly following the Chinese experience with an emphasis on early detection and strict lockdown. Definitely, these measures have allowed to slow down the virus dissemination and buy precious time. However, in a desperate bid to balance containment measures and economic stimulus, the Government seems to look to other countries, especially South Korea. In a telephone conversation between the Presidents of the two countries, the Uzbek side has requested the assistance of Korean medical professionals and the sharing of best practices.

It’s clear that Uzbekistan needs to develop its own long-term exit strategy taking into account the structure of the economy and how society functions. This requires not only evidence-based policy-making, founded on robust scientific data and methodology, but also taking ethical and strategic decisions, which will have repercussions far beyond the current pandemic situation.

The centralised decision-making system, that characterizes the governance system in the country, could turn out to be both an advantage and a hindrance. The evolving situation requires a differentiated approach as well as the flexibility to ease or restrict distancing measures in different regions and districts. The problem could be exacerbated by low legal culture among the ordinary people and state officials, as well as practices of selective justice.

The crisis has reinforced the image of the nation-state in Uzbekistan and reinvigorated the calls for a more paternalistic state, interfering in an individual’s freedoms for his/her own good. However, in the long-term, the challenge will remain to get to and stay within the narrow corridor that protects citizens’ rights and freedoms while allowing the state and society to function effectively.

Hello! Just wanted to say great site. Continue with the good work!