This post, written by Margarita Zavadskaya and Elena Gorbacheva, is the seventh in the special series “Politics&Pandemics”.

Reading time: 12 minutes

Three days ago, on May 11th, during his latest address to the nation, Vladimir Putin stated that from the 12th of May the regime of non-working days is over, and each region should proceed to gradually lift off restrictions according to their own schedule. Does this imply that the pandemic has reached the long-awaited plateau and Russian authorities handle the corona crisis successfully? This does not seem to be the case: since the beginning of May, there have been more than 10.000 new cases of coronavirus infections recorded daily in Russia. At the moment, Russia has the second highest toll of the number of COVID-patients in the world after the US. Not to mention the growing number of complaints from the business, doctors, and impoverished citizens locked in their homes.

In his first of the five addresses to the nation about the coronavirus situation on 25th of March, President Vladimir Putin declared a non-working week from 28th of March, that was prolonged several times until the 11th of May. He also outlined some support measures for business and families, but hasn’t declared the state of emergency in the country. On 1st of April the law on emergency situations in Russia was amended, and the power to declare the state of emergency was granted to the Russian government – until then only the president and the state commission on emergency situations had the right. Until this day, none of them has exercised this right. In his second address on 2nd of April, President Putin announced that he has issued an Executive Order, granting additional authority to the regional heads. From now on, the heads could decide themselves about which measures to introduce in their regions and when. After the address to the nation on the 2nd of April, the heads of Arkhangelsk region, Komi Republic, and Kamchatka Krai, resigned. All of the regions were criticised for their inefficient measures of fighting the coronavirus. The situation was especially severe in Komi, where a coronavirus explosion occurred in a hospital when a “superspreader” infected 50 people.

Alongside social and business support measures, the state planned additional support for the regions. For instance, federal subjects are exempt from paying the budgetary loans in 2020, and the governors received rights to change sources of budget deficit financing and objects of regional budget expenditures. The government allocated 65,4 billion rubles ( 817 million euros) from its reserve funds to the regions to spend on additional medical equipment. The president also ordered to forward additional 200 billion rubles (2.5 billion euros) to the regions for social and business support.

How regional diversity in terms of threat and infrastructural capacity affect the popular evaluation of anti-corona measures? Recent polls by Levada-center have registered an increase of trust in regional heads. Meanwhile, according to VTsIOM (a state-sponsored polling agency), the majority of Russians positively assess the authorities’ actions aimed at fighting the coronavirus. Denis Volkov, the leading Levada-Center analyst argues that the decline in mass support will occur months after the eruption of the economic crisis, which makes sense as public assessments usually arrive with some delay.

On the other hand, we observe a rise in new forms of protest that signal distrust with the existing policies. According to the HSE poll, half of Russians do not believe the official coronavirus statistics in Russia. On the 20th of April, online protests against insufficient state measures were organised via “Yandex. Navigator”: they started in Rostov-on-Don and continued in Krasnoyarsk, Samara, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and some other places. Offline demonstrations are rarer for the reasons of movement restrictions. However, on the 20th of April in Vladikavkaz a COVID-dissident organized a mass protest. The protesters, who declared that the Republic of Severnaya Osetiya should support the people who lost their job due to the restriction measures, also demanded the republican heads resign.

Is there any way to look at how unhappy Russian citizens are with public measures to handle the crisis? The lack of open regular polls prevents us from exploring whether governors’ support has changed during the time of the coronavirus emergency as well as the data on regional protest in Russia is scarce. Moreover, usually, the number of protests tends to decrease in times of severe economic hardship as civic engagements presume that people enjoy sufficient resources such as time, money, and education (civic skills) (Brady et al. 1995; Beissinger & Sasse, 2014). In general, protesting under non-democracies is usually more costly, especially during quarantine measures imposed by the state and prohibition to gather in public spaces. Authorities are fully authorized to prevent and detain protesters and a significant share of compatriots would deem such actions as extremely irresponsible.

Given these limitations, we decided to take a look at how Russians respect the rules of self-isolation in the regional capitals using the data provided by Yandex. The Index of Self-Isolation is based on peoples’ traffic, movement within a given location. During the quarantine, it has to be as high as possible. Following the rules and sticking to self-isolation reflect 1) the degree of trust that the danger is real and collective action should take place; 2) the degree of trust in publicly imposed restrictions and their necessity; 3) the minimal capacity to uphold the household economic well being for the quarantine time without regularly, for instance, sneaking to work illegally elsewhere, 4) the cost of disobeying the restrictions and control over them. Not to mention that it approximates the degree of civic responsibility and respect towards fellow citizens. If the index takes on high values, this stands for a high level of self-isolation and, vice versa, lower values mean that there are too many people on the streets. Thus, we assume that low levels of self-isolation even under strict quarantine regimes and higher risks of virus exposure indicate more troublesome situations in a regional capital.

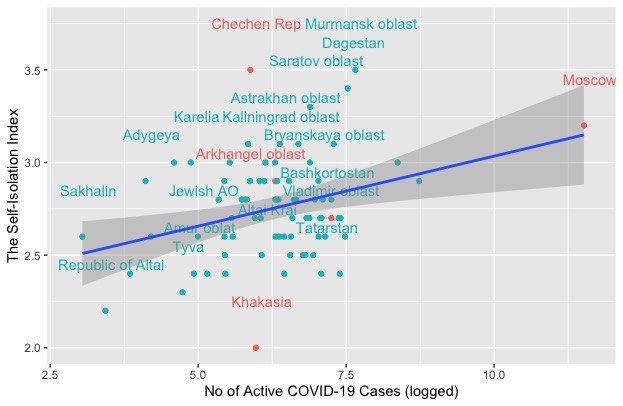

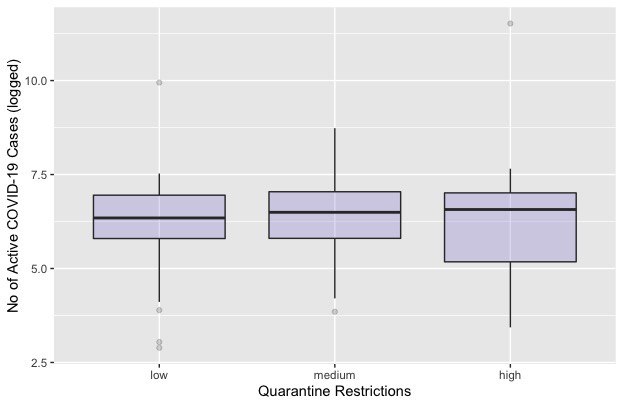

As we know, the Russian president de facto delegated the adoption of counter-pandemic measures to regional administrations. Some experts even spotted the signs of ‘federalization’ in this step. First of all, it is reasonable to expect stricter quarantine regimes where the threat is more tangible and, consequently, more respect for the self-isolation regulations. Figure 1 shows how the Self-Isolation Index varies depending on a number of active COVID-19 cases as of 12.05.2020. We see a slight positive correlation: in Samara and Moscow, the number of cases per capita is higher that came with tougher restrictions. However, we also observe over-performers such as the Chechen Republic, Komi, and Astrakhan Oblast (above the line of expected self-isolation rates, regression line) and under-performers such as Khakasia and North Ossetia. Interestingly, the strictness of counter-virus measures does not seem to correlate exposure to the virus (Figure 2). Although median values of active cases tend to decrease with tougher quarantine regimes (quarantines in most of the Russian regions were introduced in late March-early April, data on COVID-19 cases are from 12.05.2020). Three groups of regions do not significantly differ from each other. No wonder that citizens adhere to the self-isolation restrictions more tightly under stricter quarantines like in Moscow.

Figure 1. Number of active cases and Self-Isolation Index

Source: Yandex; Оперативный штаб по борьбе с коронавирусом (данные на 12.05.2020)

Figure 2. Number of Active Cases (logged) by regions with various quarantine regimes (high stands for the most strict restrictions, low – for the least).

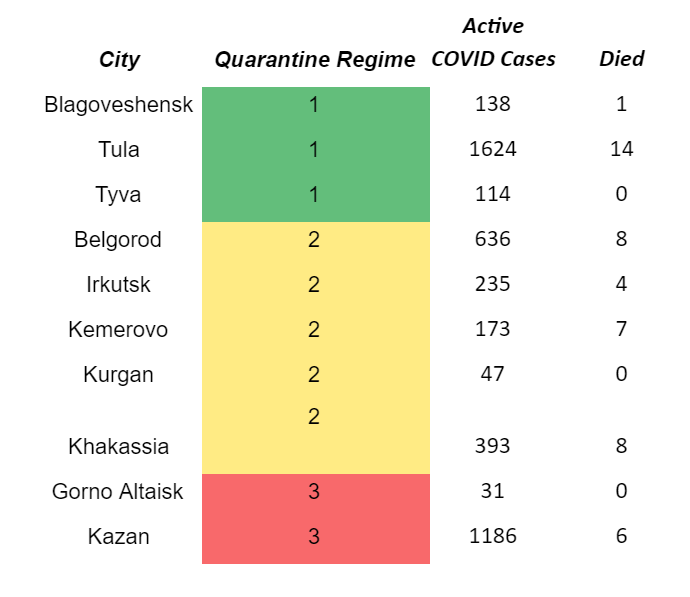

Table 1 shows the list of regional capitals with lowest self-isolation scores and their restriction regimes. Half of the cases concentrate in Siberia, only one case in Urals and Far East, three cities are from Central Russia. The latter looks particularly worrisome, while exposure to the virus is lower for more remote regions and significantly lower population density.

Table 1. The list of cities with low self-isolation scores (less than 2.5) and quarantine regimes

Source: Meduza; Yandex; Оперативный штаб по борьбе с коронавирусом (данные на 12.05.2020)

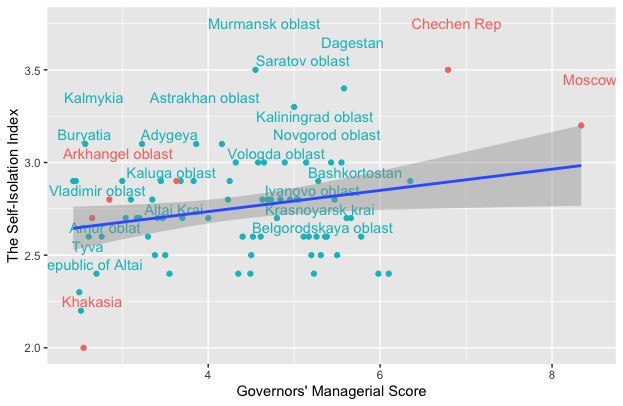

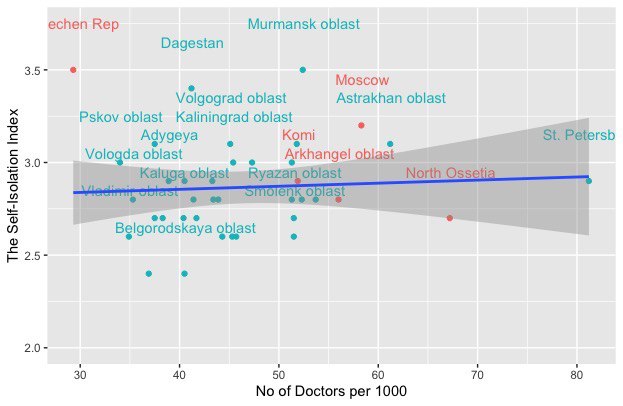

Another conjecture is that the ability to maintain self-isolation and to prevent the virus from spreading depends on the overall managerial capacity of governors, i.e. to squeeze the resources from the center and thereby upholding better infrastructure in a region including police forces, digitalization, healthcare systems, social services, etc. We approximated this managerial capacity through the number of doctors per 1000 inhabitants and the Political Management Effectiveness Score. The latter is based on expert surveys and reflects popular support, elite unity, and ties to the center (the same measure is used by Smyth et al. 2020 to compare governors’ political vulnerability). Indeed, in the regions with higher management scores implementation of quarantine seems more slightly more successful. The absolute leaders are Moscow and Grozny – the two most unrepresentative regions one could imagine – with the most powerful and politically autonomous leaders Sobyanin and Kadyrov. Meanwhile, there is very little correlation between managerial capacity and self-isolation in the rest of the regions. The number of doctors per capita does not seem to correlate with higher self-isolation either.

Figure 3. The Self-Isolation Index by Governors’ Managerial Score

Figure 4. The Self-Isolation Index by the number of doctors per 1000 inhabitants (2018)

Smyth et al. (2020) in their freshly published policy memo show the vulnerability of certain regions due to structural factors such as the number of doctors per capita and share of pensioners. Those regions with higher numbers of vulnerable populations and weaker healthcare capacities are expected to be hit harder: Komi, Arkhangelsk, Tula, Vladimir, Kurgan. We already witnessed the dismissals of governors in Komi and Arkhangelsk oblast because of the virus outbursts in regional hospitals). However, it is not necessary that the largest discontent will rise in the places hit the hardest. We would rather expect citizens to protest in regions with relatively calm epidemic situations such as Khakasia.

Decentralization of decision-making is de facto a delegation of reputational and material costs to the governors. Even those who managed to capitalize on the COVID-19 challenge will likely lose these credentials as the President announced “the good news”, i.e. the end of “the non-working days”. The latter seems risky as most of the regions have not reached the peak of the pandemic yet and even in Moscow, where the speed of the pandemic is the highest, the strict quarantine remains in place. According to the vice prime-minister Tatiana Golikova, the regions are allowed to start gradual lifting of restrictions if they fulfill three criteria: the R₀ should be less than 1, at least 50% of hospital beds of the normative number should be vacant, and the test ration should be at least 70 tests per 100.000 of population. By the 13th of May, 35 regions had started to lift off certain restrictions: in Moscow, for example, even though lockdown remains, industrial and construction enterprises were allowed to resume working. In Kaliningrad, in turn, shopping centres and beauty salons reopened. Under such circumstances, the governors are facing a dilemma whether to keep the quarantine with limited resources or lift the restrictions to send a sign of relief to the citizens and business and potentially expose the citizens to the virus.

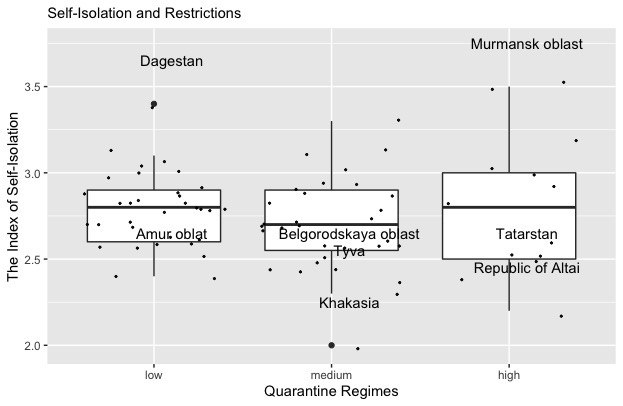

The bottom line, decentralization or devolution in the realm of fighting COVID-19 in Russia is anything but federalization or regional empowerment. This is mostly the part of “the blame game” (also see Smyth et al. 2020) where costs of painful measures are shifted to the regions and ‘good news’ are delivered by the president even at the price of the premature celebration of victory over coronavirus. Rates of self-isolation somewhat depend on the strictness of quarantine, but there is surprisingly a lot of variation where citizens do not stick to the self-isolation even under tougher control and, vice versa, there are regions where citizens respect the regulations despite the more permissive conditions. Since there is no direct way to know people’s approval, it could be a proxy for more problematic territories. One way or another, economic factors will be decisive in determining who is to blame and for what and the growth of public discontent is yet to come.

Figure 5. The Index of Self-Isolation by Quarantine Regimes

Source: Yandex; Фонд “Петербургская политика”

2 Replies to “Concentrating Benefits and Delegating Costs: How the president undermines the governors’ chance to raise their own political credentials while handling the pandemic”