Six years ago, New York Times journalist Gary Shteyngart spent a week in a Manhattan Four Seasons hotel exposing himself to the Russia Today news channel 24/7. He described his experience daily and in the end reported severe emotional exhaustion, fatigue, and astonishment at how people who are forced to consume highly politicized and low-quality content can remain decent human beings. This summer, from the second half of June until the 18th of September, our project team conducted media monitoring of the 2021 State Duma elections for the Movement for Defence of Voters’ Rights “Golos” – a Russian organisation established in 2000 to protect electoral rights of citizens. Unfortunately our team was not provided a 5-star hotel, but on the other hand, we were luckily not exposed to 24/7 media observation. We took up the task of monitoring the five main Russian TV channels from June to September this summer to evaluate the media coverage of all political parties participating in the State Duma elections. In this brief post, written by Elena Gorbacheva and Margarita Zavadskaya, we share our experience and observations with you.

On the 18th of August 2021, Golos was labeled a ‘foreign agent’ by the Russian authorities, however, this was not the first time. In 2013 the authorities registered Golos as a domestic election monitor on the list of foreign agents as a nonprofit organisation. After 2013, Golos continued to work as a non-registered movement and as of 2021 the organization officially became the first entity to be put on the list of foreign agents covering unregistered groups. “Golos” still remains the only independent election watchdog currently active in Russia.

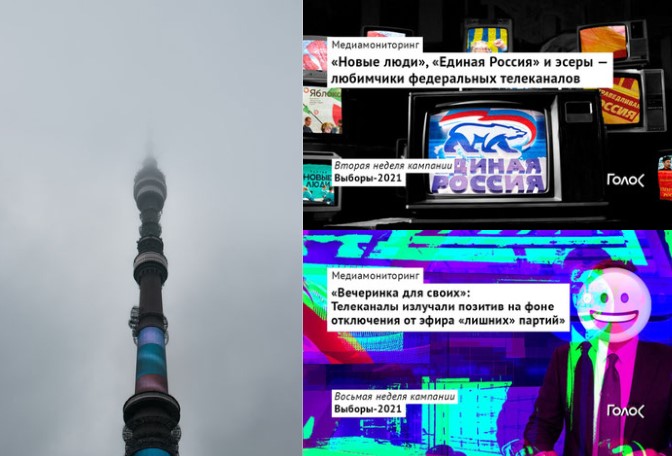

For 13 weeks in a row, our project together with six student volunteers from Russia and Finland watched every newscast on five Russian TV channels – Channel One (Pervyi kanal), Russia 1 (Rossiya 1), NTV, RenTV, and Fifth channel (Pyatyi kanal). On average, every week there were around 150 newscasts across these channels lasting from 5 minutes to 2 hours.

Television still plays an important role in Russia: according to the Levada Centre, 62% of people in Russia report that television is their main news source, though the number has declined from 90% in 2016. Thus, it is important for the integrity of elections that the channels would cover all the parties and candidates in an equal and neutral manner. According to article 45 of the Federal Law FZ-67 “On Basic Guarantees of Electoral Rights and the Right of Citizens of the Russian Federation to Participate in a Referendum”, “[i]n television and radio programs and in the publications appearing in the printed media, reports concerning election events, events related to a referendum shall be presented in exclusivity in the form of separate news items, without any comments. Such news items shall not give preference to any candidate, electoral association, referendum initiative group, another group of referendum participants, including with regard to the time dedicated to cover their election activities, and the amount of space allocated in the printed media for such reports”.

Our team monitored newscasts to evaluate how elections and/or parties were represented by each channel. Our observers recorded how long different segments that discussed elections and parties lasted and what the tone of the coverage was: positive, neutral, or negative. From the experience of previous research groups that monitored the presidential elections of 2018, we know that the task is rather challenging: not only physically but also mentally. It is not easy to be bombarded by politically charged information for 13 weeks, even if we divided the channels so that one observer watched only one channel per week with some breaks. Four of the students who worked for us were from Russia and two from Finland. One of them speaks Russian language as a second foreign language, which added an additional challenge, though this project proved to be excellent language practice. After the election campaign was over, we asked the students to share their experiences of media monitoring.

As bad as we expected?

Most of us have not watched Russian TV for years, while others have never watched it. However, we all had strong expectations that we were going to be brainwashed most of the time. We cannot say that the reality proved very different from our expectations, though there were important nuances.

A Russian political science student recalls that:

“It was harder than I expected. TV watching appears to be an easy (non-)activity and this was true at the beginning of monitoring, but as the end of the campaign approached, the intensity of coverage on party activities increased. The most tedious part of the work was highlighting and characterizing only a few seconds of airtime that was allotted to most of the Russian parties.”

Students from Finland paid more attention to their mental state:

“The work turned out to be harsher on my mental health than I expected” (student of media studies).

“For the most part, yes, the monitoring reflected my expectations. I’ve heard many times before that the ruling party (United Russia) was mentioned in the media much more often than other parties, and I received confirmation of this. Although we can say that, in a sense, I was surprised that in some weeks on my channels there was almost no mention of other parties except United Russia” (student of political science and journalism).

Watching propaganda for three months

Even though students are now more familiar with Russian realities from observing three months of news coverage, students still agreed that their opinions of the Russian electoral system did not change due to the experience of professional education. One student emphasized their frustration and decrease in trust to any – even non-political – news:

“No, my opinion about the elections has not changed in any way. I knew before that there was a powerful manipulation of social preferences. Rather, the opinion about the media, namely about the content, has changed. Now it seems that most of the news stories are completely non-objective and do not even strive for this. Quite often, controversial information appeared in the stories. You can probably say that my trust in existing television media has dropped to almost zero” (student of political science).

“I am a very phlegmatic person, so I can’t point out any psychological consequences, but at the beginning I had headaches” (student of political science).

Finnish students admitted that they now have a deeper understanding of the nuts and bolts of one-sided transmissions of political information:

“I knew that the main party gained way too much attention, but I did not know how (emphasis added) it was done. Now I have a clearer image of what propaganda or hostile media environments can be and how [Russian] TV news picks very few topics to present. It did not change my opinion on media as a whole, but this offered a very clear point of view on how the federal channels’ TV news is produced. I understood better what topics are mostly covered, what the tone of the coverage is and how it is different from Finnish TV news. It clearly has a very similar structure, but the angle on the topics is very different” (student of media studies).

“I noticed myself getting frustrated with the way events were portrayed in the news. It seemed as if everything was fine in Russia, and anything negative was the fault of foreign powers. The news anchors were not neutral, but either gave praise to some Russian politicians (especially from Edinaya Rossiya) or made really snarky remarks towards others (like KPRF)” (student of political science and journalism).

Watching hostile media, i.e. those that repeatedly transmit untrustworthy and / or aggressive content, takes its toll on one’s emotional well-being. One of the Finnish students confessed that regular exposure to the content you disagree with causes frustration, hopelessness, and even mental burnout. Perhaps, these feelings are close to emotions experienced by people who live in Russia and oppose the government:

“It turned out that Russian news can make you sick, which made me question my ability to continue within the project. At first, I kind of tried to laugh about everything and everything seemed mostly absurd, but eventually the feeling about the absurdity of the current situation in Russia considering the political repressions became overwhelming and some political characters of the most represented party almost caused physical revulsion, which was a surprisingly strong reaction. I thought that I would mostly get used to everything and that it may make me even numb, but it had an opposite effect. I started noticing feelings of frustration, anger, and hopelessness. I even noticed that other symptoms of mental burnout started evolving” (student of media studies).

Students point out that some topics were covered with a tone that seemed to evoke “a certain level of affectation, hostility and sensationalism”. Some of the most pressing issues in the world today were simply ignored in Russian TV news broadcasts, such as global warming or problems in domestic politics. Alternatively, newscasts constantly aired attacks on the US or Ukraine in which everything these countries did is wrong, creating a doubtful pleasure for the audience.

Interestingly, Russian students highlighted that media seeks to create a comforting worldview, overlooking negativity and stressing achievements:

“Three months of viewing convinced me that the existing media is mostly concerned with creating a comfortable political agenda. Most information is biased and “inconvenient” news simply does not reach the viewer. Probably, my trust in television has been greatly reduced, given the fact that I did not trust information from television much before” (student of political science).

Coping with propaganda

Some experts watch Russian television out of professional interests and perhaps have an ability to emotionally distance themselves from the content. When we started the project, we were aware that it is barely possible to change one’s opinion if one is exposed to messages that contradict one’s worldview. We approached the task with a certain degree of curiosity that was gradually replaced with fatigue and frustration.

“There was a big temptation to fast-forward some parts of the program that seemed to be repeating from the previous ones. But this could be dangerous due to the small changes broadcasters make from release to release – some completely apolitical plot about fruit and vegetable harvests can turn into an advertisement for the ruling party” (student, political science, Russia).

“Probably the most difficult thing for me was watching the same videos throughout the span of one day. … For example, I remember how often there were references to the fact that the elections in Russia are the most honest and open, and all possible violations and falsifications were fake news from Western countries. Such stories appeared in different formats – as interviews from experts and as separate full-fledged stories” (student, political science, Russia).

Finnish students to a greater extent paid attention to the brutality and violence in the newscasts that are not typical of Finnish television.

“Another challenge was to deal with the brutality of some clips or contents like showing people being hit by a car or discussing violence in detail. If I knew there could be visually triggering content present, I tried to watch less and listen more, when it came to the clips on war or violence or accidents. … Multiple repetitions at some moments were very depressing . To cope with this, I was helped only by a short timeout [from content observation] and the understanding that in reality all these plots are aimed to hide the real state of affairs. For example, that election violations are not fake, but a real practice for winning elections” (student, media studies).

Studying sensitive topics and the danger of professional burnout

Carrying out empirical research is always a hard mission. Carrying out research in contexts that are emotionally triggering and even toxic pose a genuine challenge to researchers. Students of political or home violence, genocide studies, war, crime, discrimination, prisons, abuse and hate speech have to deal with psychologically challenging content. Monitoring news does not sound like a challenging task. We are even convinced that there are viewers who sincerely enjoy the content of Russian news. Existing research in the realms of media and political studies suggests that viewers’ political and ideological preferences filter all the incoming information. If the message is congruent to the viewer’s worldview, she would gladly agree with it and it would reinforce her vision of reality. If the message speaks against the viewer’s stance, it is either ignored or provokes irritation. We also believe that constant reflection on the work we are doing provides us with better methodological support and, what is even more important, a healthy distance from the subject. For this reason, we think it is crucial to give a word to those who produced the research data we further rely on.

“This may sound clicheé-ish, but the thing is that I was able to support the organization that’s work I appreciate, to do something that can help a more democratic scene in the future, but also understand how activism and science can be bound together and do something meaningful, which was very useful for me personally” (student, Russian culture and media, Finland).

“Yes, of course, it was an extremely interesting experience for me. Probably, I have not watched any news this much in my life. This experience made me think about the functions of the media (television in particular) in authoritarian regimes and, in general, about how important the “necessary” information is for such a regime’s “favorable” functioning” (student, political science, Russia).

All in all, despite the challenges, we are happy to have worked with Golos. We all received something out of this project, be that helping an organisation we respect, collecting unique data, learning how to work with said data, practicing Russian, or better understanding how Russian media and election campaigns work. We plan to use the collected data in the future in some way. We shared our initial takeaways during the expert discussion on Russian elections 2021, which was organised on the 8th of October.