The spring semester has just started but is already looking promising. Our EMaRB project is going to continue to work on the dataset, but in addition to that we will keep up with our tradition of organising seminars, where researchers present their work on elections, malpractice, and cyber-security in Russia and beyond. In this post, we are introducing our spring programme and we hope to see you at our events very soon!

Elena Gorbacheva, Doctoral researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute: ‘Electoral consequences of environmental protest: The case of Shiyes’, 23.02.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Elena Gorbacheva, Doctoral researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute: ‘Electoral consequences of environmental protest: The case of Shiyes’, 23.02.2022, 14:00-15:30.

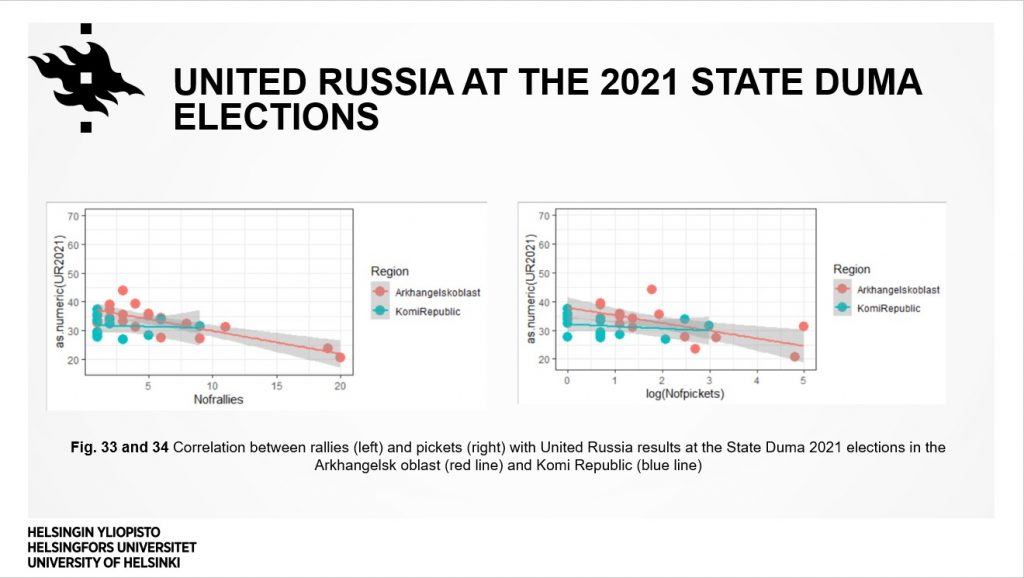

The Shiyes protest campaign, which lasted for about 2 years since summer 2018, became one of the most prominent and well-known environmental protests in Russia during the last decade. The protests resulted in success – the landfill project for Moscow waste in Arkhangelsk oblast’ was cancelled and the head of the region, who supported the construction, resigned. But are there any other consequences of the two-year contention?

In this presentation, I am examining the political consequences of environmental protests in Russia by studying environmental protests in the Arkhangelsk region against the Shiyes landfill and how they affected the political support of incumbents at the elections of different levels in the region.

Philipp Chapkovski: ‘Unintended consequences of corruption indices: an experimental approach’, 29.03.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Philipp Chapkovski: ‘Unintended consequences of corruption indices: an experimental approach’, 29.03.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Using the results of a large-scale (N=900) online experiment, this paper investigates how the information about regional corruption level may deleteriously affect interregional relations. Corruption indices are widely used as a measure of the quality of governance. But in addition, to be a valuable tool for investors and policymakers for making informed decisions, they may also result in statistical discrimination: people from a more ‘corrupt’ region may be perceived as less trustworthy or more inclined to dishonest behaviour.

In our experiment, we manipulated the number of information people have about three different Russian regions in two simple behavioural games (‘Cheating game’ and Trust game). In a Cheating game after the main stage where they report whether they observed a head or a tail on a flipped coin, they guessed how many participants in each of the three regions reported heads. In the baseline treatment, we provided them with a set of generic information about each region (such as population size and share of females), and in the main treatment, they were additionally informed about the degree of corruption in each region. They also had to make a transfer decision in the standard trust game for three potential recipients in each region. The presence of corruption information made people substantially overestimate the degree of dishonesty in more ‘corrupt’ regions. The behavioural trust towards a person from a region was also significantly lower if the region was marked as ‘corrupt’. The results demonstrate the potentially harmful unintended consequences of corruption indices that have to be taken into account by policymakers.

Iuliia Krivonosova, Doctoral researcher at Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia, and at the Kompetenzzentrum für Public Management, University of Bern, Switzerland: ‘Internet voting in Russia: Democratizing Power of Internet Voting Revised?’, 11.05.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Iuliia Krivonosova, Doctoral researcher at Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia, and at the Kompetenzzentrum für Public Management, University of Bern, Switzerland: ‘Internet voting in Russia: Democratizing Power of Internet Voting Revised?’, 11.05.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Internet voting has pride of place among democratic innovations. It enfranchises new groups of voters, brings greater voter convenience and decreases costs of voting (Alvarez & Hall, 2003; Goodman & Stokes, 2016; Krimmer, 2012). So far, the studies of Internet voting implementation have been limited to democratic countries, which helps to reinforce the narrative of Internet voting as an innovation with democratic potential. At the same time, authoritarian regimes have a lot of potential to become norm entrepreneurs (Sunstein, 1996) generating new “alternative norms of appropriateness” (Jones, 2015, p. 26) which has already happened in the field of cyberspace (Kneuer & Harnisch, 2016) and e-participation (Åström et al., 2012). Therefore, for Internet voting to be an innovative solution, it deems important to study its development in a non-democratic environment. I consider one of such cases – Internet voting implementation in the 2019 Local elections in Moscow, Russia – in order to answer the research question “How is Internet voting implemented in a non-democratic environment?”

Elena Gorbacheva, Doctoral researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute: ‘Electoral consequences of environmental protest: The case of Shiyes’, 23.02.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Elena Gorbacheva, Doctoral researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute: ‘Electoral consequences of environmental protest: The case of Shiyes’, 23.02.2022, 14:00-15:30. Philipp Chapkovski: ‘Unintended consequences of corruption indices: an experimental approach’, 29.03.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Philipp Chapkovski: ‘Unintended consequences of corruption indices: an experimental approach’, 29.03.2022, 14:00-15:30. Iuliia Krivonosova, Doctoral researcher at Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia, and at the Kompetenzzentrum für Public Management, University of Bern, Switzerland: ‘Internet voting in Russia: Democratizing Power of Internet Voting Revised?’, 11.05.2022, 14:00-15:30.

Iuliia Krivonosova, Doctoral researcher at Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia, and at the Kompetenzzentrum für Public Management, University of Bern, Switzerland: ‘Internet voting in Russia: Democratizing Power of Internet Voting Revised?’, 11.05.2022, 14:00-15:30.