Arriving at the Baraban Epilepsy Research Laboratory typically involves either climbing eight flights of stairs or waiting an unsettlingly long time while the elevator, long overdue for repairs, shudders its way to the desired floor. My lethargy usually precludes expediency, and I regularly find myself squished in at the back of the enclosed container. On the plus side, the elevator talk is often entertaining; grumblings over the embarrassment that is the elevator, this effectively lightens the figurative load.

Such morning elevator business is, for the moment, an experience of the past. As of March 8th, 2020, the Baraban Lab has been asked to shut its doors and clear the way for the surge of patients anticipated to arrive at the University of California San Francisco hospital, in the coming weeks. Despite strict social distancing orders, our lab may still execute essential lab functions, all of which pertain to the fish room.

Upon entering the fish room, located on the far end of a generously sized lab, one is immediately struck by rows of tanks, stacked floor to ceiling. The tanks, which contain different lines of zebrafish, receive a continuous flow of water, supplied by one or two small hoses per tank. If one of those narrow hoses were to become dislodged, constant dripping would ensue, perhaps unnoticed for several hours, accumulating on the floor of the fish room, and eventually flooding out the door and into the hallway, creeping dangerously close to the microscopy room. A hypothetical of course, one that most definitely did not happen, and certainly not on the second day of the quarantine.

Aside from posing a potential flooding hazard, which has now been remedied with flood sensors and 24 hour camera surveillance, the zebrafish of the Baraban Lab are very special fish, together representing approximately thirty eight lines of human loss-of-function gene mutations associated with epilepsy. Each fish line is screened for epileptic phenotypes through careful examination of EEG recordings, behavioral abnormalities, and survival rates.

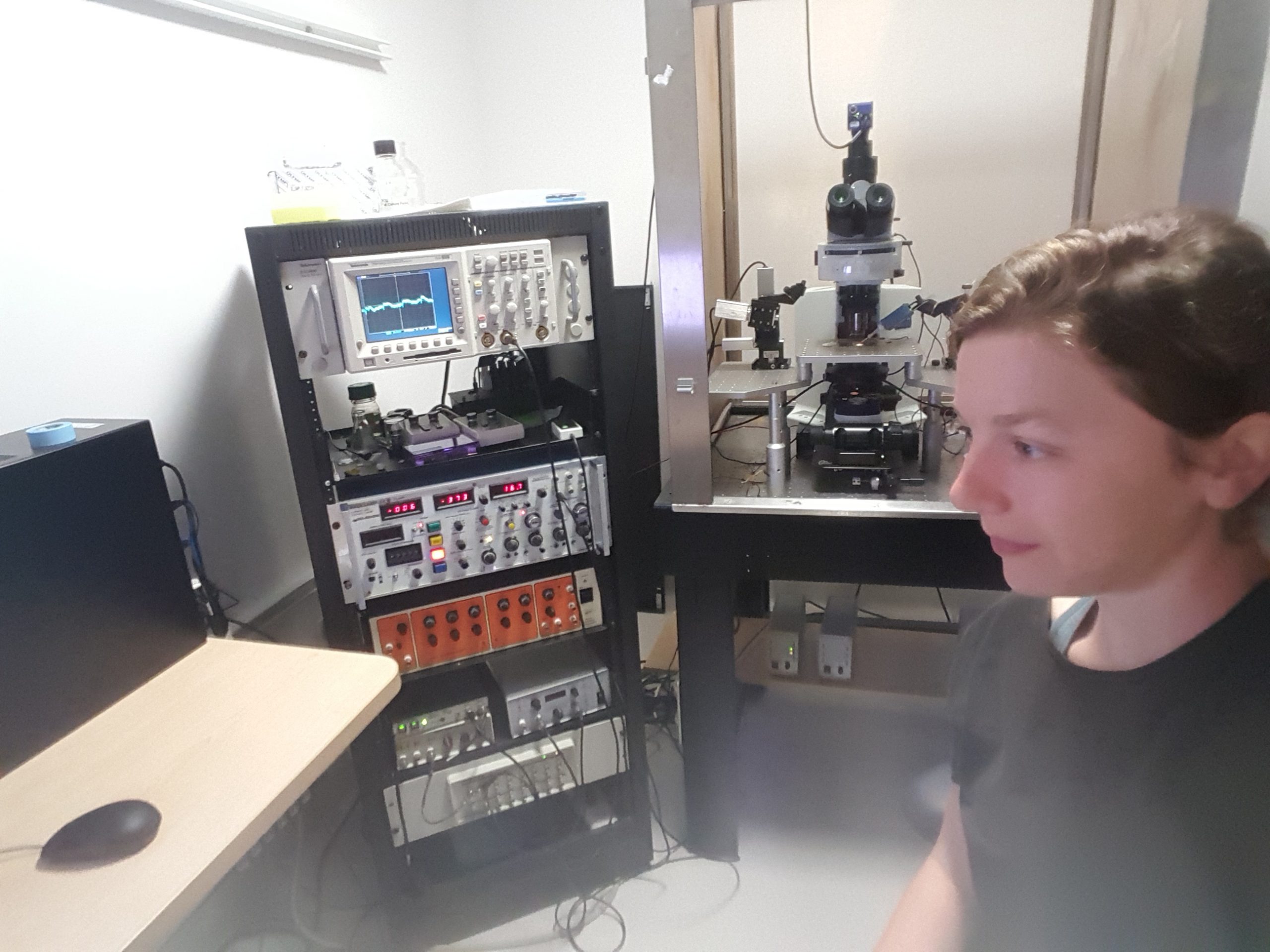

My master’s thesis project contributes to the EEG screening phase of the project in which, remarkably, a small glass electrode is placed in the optic tectum of a live zebrafish larva. The larva, which is no thicker than a human eyelash, is immobilized in an agarose gel, allowing for localized field recordings of real time brain activity. Completion of the epilepsy zebrafish project will bring the findings of the “aquarium” closer to the bedside of the patient and create a foothold for the advancement of personalized treatment for individuals suffering from refractory epilepsies.

Outside of the lab, my UCSF ID badge has afforded me access to events on all UC campuses in San Francisco with a free shuttle bus ride to each location, which is a luxury in this city. I have attended animal handling and surgical courses, first aid training, as well as bioscience seminars on topics ranging from the relationship between gut health and neurodegenerative disease to the implications of placental development on maternal health, as well as a lecture on the dangers of unregulated radiation doses administered during CT scans. It has been a gift to be able to round out my University of Helsinki master’s training at another institution, and I am deeply grateful to HiLIFE for supporting me over the past 6 months. Thank you, Dr. Baraban, for accepting me as a part of the team, for your continued mentorship, and unrelenting patience.