On Monday, 1st of June, President Putin signed the executive order on setting the date for the nationwide vote on amendments to the Constitution of the Russian Federation. The vote was originally scheduled for the 22nd of April, but it was postponed until further notice in late March due to the spread of the coronavirus in Russia. According to the executive order, the nationwide vote will take place on the 1st of July. The vote will start after the postponed to 24th of June Victory Parade and will end before the start of first school graduation exams, which were also postponed. All Russian regional legislatures and the Federal Assembly have already approved the amendments in March. After that, on 14th of March, Putin signed a bill according to which the amendments will be effective after Russian population approves them through the national vote. Amendments will be passed if more than half of the voters support them, and there is no requirement for a voter turnout percentage for voting to be eligible. This week, in our ninth post of the “Politics and Pandemics” special series, Margarita Zavadskaya and Elena Gorbacheva comment on the national vote and how the ongoing pandemic will and already is affecting it.

Reading time: 9 minutes

Voting on constitutional amendments is heavily loaded with symbolic value for the current regime and most importantly aims at extending V. Putin’s presidential terms. All this comes in a single package with extravagant textual novelties such as support for ‘traditional family’ to shift the attention and to lure conservative and unsophisticated electorate. Usually, natural and health disasters boost political support thereby spurring the rallying effect in the population. On the other hand, the economic situation is getting grimmer and there is a large consensus among observers that the existing policy measures to support citizens, vulnerable groups, and business are ill-designed, insufficient, and untimely. So far, political responsibility has been shared in a way that the president delivered ‘the good news’, while dealing with unpleasant practicalities was delegated to the government agencies and regions. The question is whether the regime is attempting to catch the wave of national rallying around the leader in the times of the pandemic?

As long as the decision to extend V. Putin’s presidential terms by means of the constitutional vote had taken place before the COVID-19 emergency, further postponement of the vote is utterly undesirable as the economic conditions will worsen. This is not to say that Russian voters would immediately withdraw their support from the president – usually, under non-democratic regimes, political support has significant inertia and may remain high even under dramatic economic downturns – however, this increases the uncertainty and may give more leverage to the opposition. At the meeting with Vladimir Putin on 1st of June, co-chair of the working group to draft proposals on amending the Constitution Taliya Khabriyeva stated, that the relevance of the amendments was highlighted during the pandemic, as, in Khabriyeva words, the breakthrough in COVID-19 treatment is not possible without proper legal regulation of science, which is not possible under the current Constitution. Thus, the timing is of utmost importance to have the mission accomplished.

How the vote is going to look like given the alarming situation with the COVID-19 in Russia? Chair of the Central Election Commission Ella Pamfilova promised that all people participating in the voting will be equipped with face masks, gloves, and single-use pens, and there will also be hand disinfectants at place. All members of election commissions will be tested on coronavirus, and voters’ temperature will be checked. Additionally, Pamfilova suggested that the voting would be taking place for 6 days before the official date on the 1st of July so that fewer people would be present at polling stations. Voting at home opportunities will be also enhanced for those who cannot come to the designated stations, and online voting might be organised in 2-3 regions. Pamfilova also mentioned that Russia reflects on the experience of other states who held elections during the pandemic, and said that Russian procedures will be even more efficient. For example, Russia will not use voting by post, as this procedure, according to Pamfilova, cannot be efficiently controlled neither in a sanitary sense nor under considerations of election observation. Vote by post was, however, enabled on the 13th of May this year.

Restrictions due to coronavirus are still largely intact in Russia: in Moscow, for example, the citizens are still obliged to wear masks and gloves on the street, and from June they are allowed to go on walks 3 times a week according to their house schedule. Besides, chief sanitary doctor of St. Petersburg Natalya Bashketova said this Tuesday that the city is absolutely not ready for the lifting of restrictions. The daily increase of registered coronavirus infections is still more than 8.000 cases in the whole country.

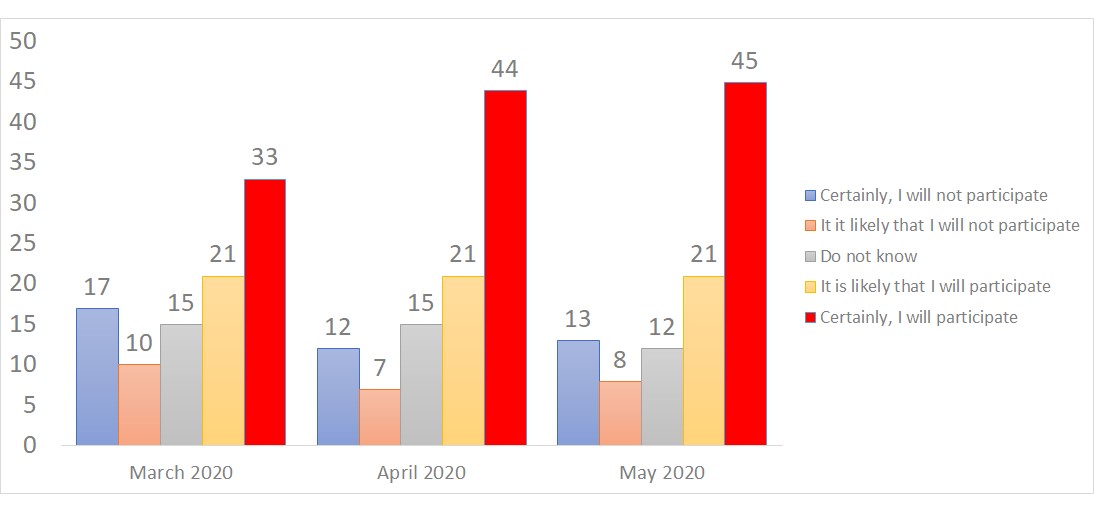

Figure 1. Expected Turnout on the National Vote on the 1st of July, 2020, Russia

Source: Levada-Center, Survey of 22-24.05, N=1623 aged older than 18; CATI & RDD sampling procedure.

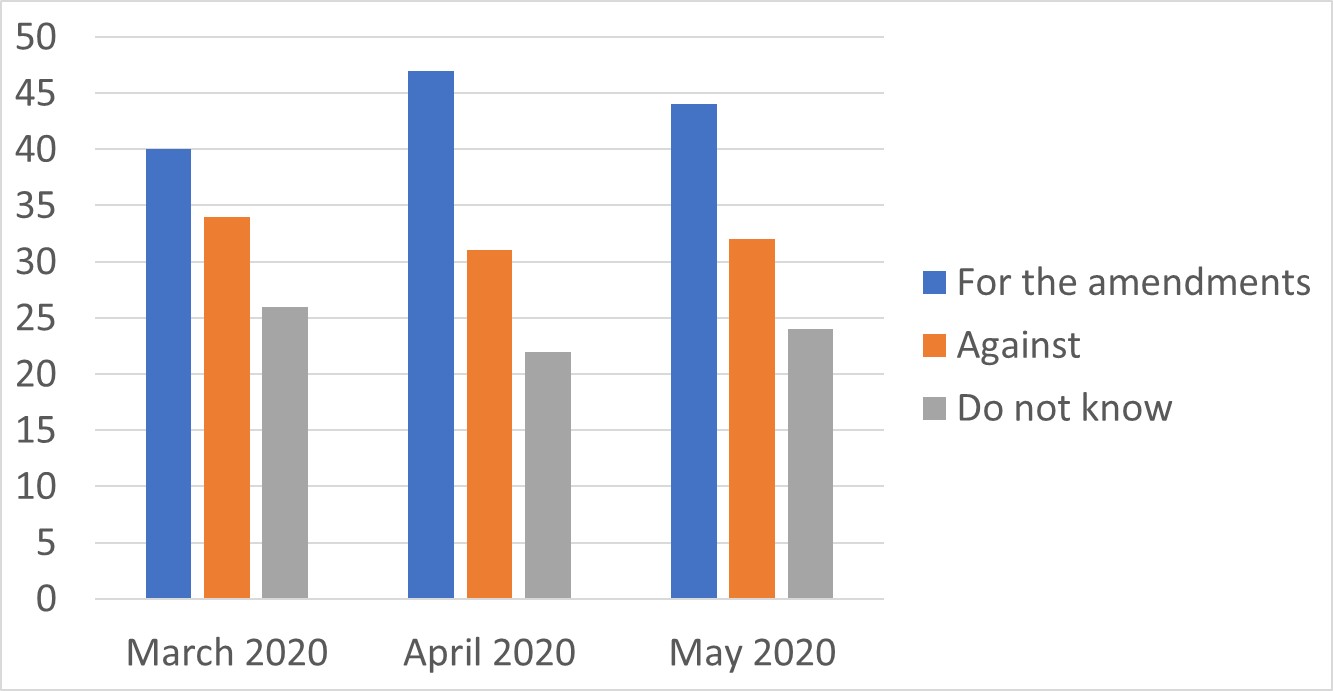

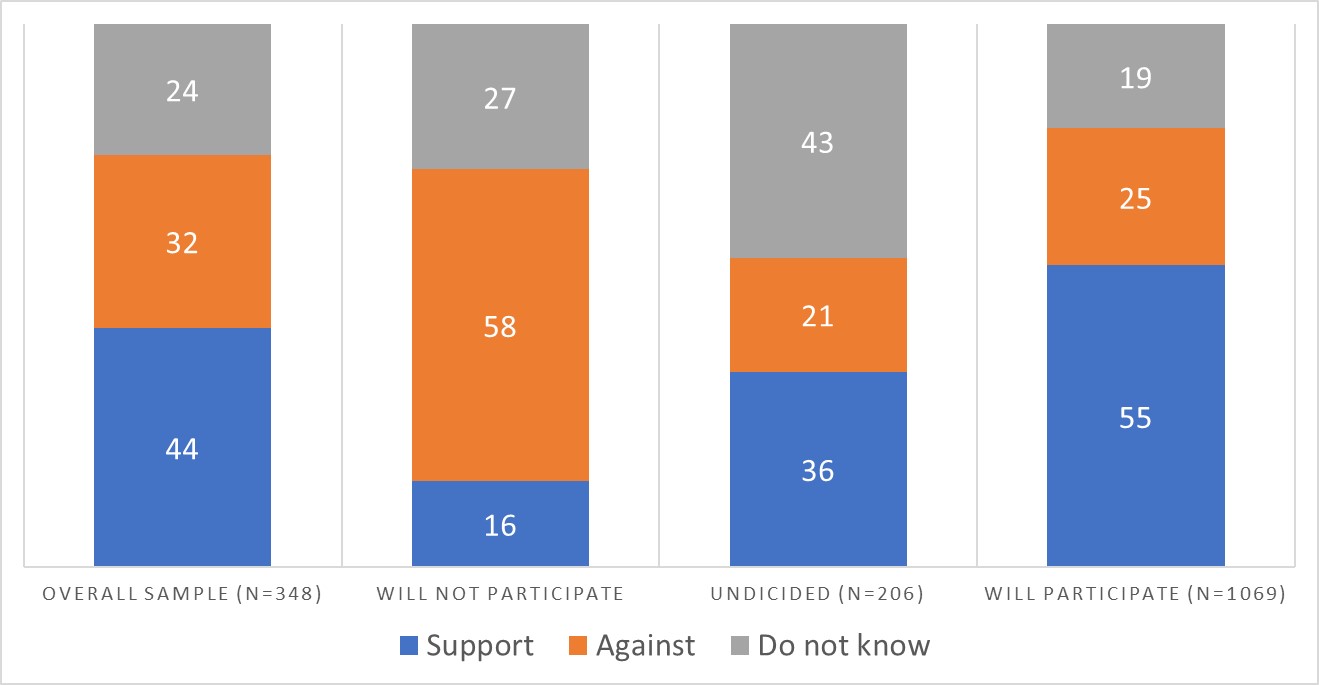

How many Russians plan to participate given the pandemic restrictions and how their attitudes towards the amendments changed throughout this Spring? So far, the number of those who intend to participate in the constitutional vote has increased since March 2020 from 33% to 45%: those who were undecided in early Spring have been ‘activated’. While the number of those who decided to refrain from vote remains stable – 21% (see Figure 1). The share of people who are in favour of the amendments has somewhat increased – from 40% in March to 44% in late May. The share of oppositionists has slightly dropped from 34% to 32% (see Figure 2). More than 20% of respondents do not have a strong opinion. Figure 3 vividly shows that most of the supporters plan to turn out at the polls, while non-supporters will stay home – 58% of non-participants express negative views on the proposed amendments. All in all, loyalists tend to be more active, while the opposition seems to ignore the very event. There is little doubt that the amendments will pass, however, it will leave more than one-third of Russians unsatisfied, not taking into account that the share of those with no clear opinion is also high – 24% (Figure 3). To argue that there is a consensus behind the new constitutional terms would be a strong exaggeration.

Figure 2. Support for the Constitutional Amendments from March to May

Source: Levada-Center, Survey of 22-24.05, N=1623 aged older than 18; CATI & RDD sampling procedure.

Figure 3. Support for Constitutional Amendments by Expected Turnout

Source: Levada-Center, Survey of 22-24.05, N=1623 aged older than 18; CATI & RDD sampling procedure.

The forthcoming vote has a number of issues from the legal viewpoint: 1) the vote does not qualify as a referendum as it did not pass all the necessary requirements according to the federal law on referendums¹; 2) unclear legal criteria to define if the voters supported the cause (is absolute majority enough?); 3) as long as it does not fall under the existing electoral legislature, requirements for voters’ identification, the secrecy of vote and public campaigning are loosened. As the experts from the independent observer organization “Golos” argue, ‘such decisions – carrying out of ‘the vote-that-is-not-a-referendum’ – undermines the law’ and it shows that ‘any legal prohibition may pass through the invention of new extra-legal mechanisms’. Legal experts claim that it is unacceptable to pass constitutional amendments as ‘a package’ not united by a common subject.

To make a long story short, it is not a referendum. The vote’s ‘extra-legal status opens up a wider range of tools to compromise electoral integrity and to use most of the options from ‘the manipulation menu’ (Schedler 2002): turning a blind eye to the violations that aim to support the cause and sanctioning selectively the attempts to protest, to mobilize against, or even to observe the voting process. This is why, this is neither a referendum nor an expression of voters’ preferences in a strict sense of the term. What we are dealing with is a sort of ‘electoral event’ with a dubious legal status.

The impact of COVID-19 on electoral innovations turns out ambiguous as well. The pandemic helped to justify a number of innovations that, at first sight, may even look progressive, but in reality will serve to lower the costs of rigging elections. These innovations include 1) extension of the voting period; 2) online voting²; 3) restrictions on mass gatherings. The online vote was used for the first time at the Moscow city elections in 2019 and proved to favor loyal candidates – in all competitive districts with electronic vote loyal candidates won. Mobile voting strongly correlates with the vote for the incumbent (see Saikkonen and White 2020), so voting online will operate in a very similar way and will make voting less transparent. An extended number of polling days will provide more information on how the vote proceeds and facilitate technical adjustments. However, it is not the expected violations and how to prevent them that pose a challenge for the Russian opposition, but rather the very status of the vote. The opposition faces a dilemma whether to focus on procedural legitimacy and technicalities of a legally ambiguous event or to challenge the core of it – the nullification of the terms served by the current and former presidents of the Russian Federation.

¹ At the same time, according to the Russian legislation, the chapters of the Сonstitution that are being changed do not require any referendum in order to be amended.

² The possibility to cast the ballot online will be available in a maximum of 3 regions.