Pandemic throws a monkey wrench into many plans, including national elections and in some special cases like Russia – attempts to call ‘a referendum’ or symbolic vote to support constitutional amendments that will extend the president’s term in power. Electoral timing has always been a highly sensitive issue for political elites: in Westminster democracies, early elections are a way to extend the government’s longevity and to surf the wave of massive support, in others – electoral time-table is exogenous and can be altered only under extreme circumstances. The COVID-19 epidemic is definitely one of those. Here we collected the data on all the countries that scheduled elections and/or referendums, whether these countries altered electoral schedules given the pandemic and how it affected electoral outcomes. This is the fourth post of our special coronavirus series “Politics & Pandemics”, written by Margarita Zavadskaya and Elena Gorbacheva.

Reading time: 10 minutes

We summarized the data on the pandemic, COVID-19 counter-measures, and voting from the IDEA and V-Dem datasets (see Table 1). In total there are 25 elections from February to July 2020: 10 legislative elections, 3 presidential, 7 general elections, and 6 referendums. Among these countries, we have 9 autocracies that hold elections (aka electoral authoritarian regimes, Schedler 2002, Morse 2012) and 16 democracies. In this set, there is only one EU country – Poland that introduced strict restrictions already started to lift them and refuses to postpone the national vote. All in all, 8 electoral bids were postponed and 8 took place according to the schedule; 6 elections are still scheduled.

Elections are a political focal point that allows key political actors to coordinate on a number of hot policy issues. Sometimes, not just metaphorically, but literally – on polling stations and while rallying in case they are unhappy with electoral outcomes or procedures (e.g. Israeli protests against the government respecting the 2 m distance between the protestors). In the times of the pandemic, gatherings are banned and social distancing is required. Not surprisingly, most of the autocracies from our table immediately introduced the restrictions or bans on all sorts of gatherings and events, including Russia. Meanwhile, other measures came with a delay and most of the autocracies never introduced full lockdown and state of emergency.

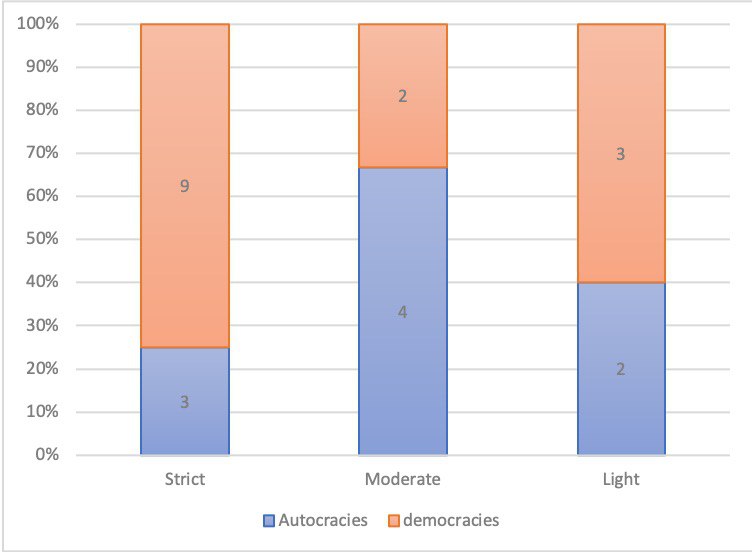

Do political leaders deal with the electoral time-table responsibly and how unexpected disruptions affect the governments and regimes? Autocracies that hold elections tend to introduce milder restricting measures: partial lockdowns, ban on public gatherings. Only two countries declared the state of emergency – Guinea and Mali (no taking Syria into account that it is already in the state of war). Democracies are somewhat stricter, although there are countries with light restricting regimes such as Iceland and Mongolia – countries with low population density, Vanuatu – a tiny island state with no registered COVID cases, and, finally, South Korea where the peak has already passed. No doubt, that the number of countries – just 22 cases – does not allow us to provide any strong evidence of a linear or perhaps inverted U-shaped association between the level of democracy and restrictive measures. But it still gives some grounds to speculate that autocracies – including Russia – may want to strike the balance between unwanted protest activity and allowing the business and main constituencies to avoid economic harm with a full lockdown.

It must be noted that in all 8 elections that had taken place so far, all ruling parties and groups remained in power and even gained additional support (see Table 2). In the case of South Korea that triumphantly defeated the virus, the governing Democratic Party in coalition with ‘Together Citizens’ won with a landslide results of 49.91% and 33.36% respectively and with the highest turnout of 66% since 1992. An important side note: the vote took place under a new electoral reform that introduced compensation seats within the proportional representation (PR) tier of the mixed electoral system. As observers comment, “in response, both major parties set up satellite organisations that only competed for PR seats”. In Israel, another reshuffle in the governing coalition occurred, but without dramatic changes. In non-democratic Iran, Guinea, and Mali with weak or non-existent political parties the results do not reflect genuine people’s preferences, but rather states’ mobilization capacity.

Figure 1. Restrictive measures across democracies and autocracies (N=23)

Sources: IDEA, V-Dem, and variety of media reports

Table 1. Overview of elections and referendums whose time overlapped with the COVID-19 outbreak: February – July 2020

| No. | Country | Elections | Scheduled date | Status | Type | Regime |

| 1 | Iran | Leg | 21.2 | Held* | Moderate | Autocracy |

| 2 | Israel | Leg | 2.3 | Held | Moderate | Democracy |

| 3 | Guyana | General | 2.3 | Held | Strict | Democracy |

| 4 | Vanuatu | General | 19-20.3; 19.4 | Held | No | Democracy |

| 5 | Guinea | Leg+referendum | 22.3 | Held | Strict | Autocracy |

| 6 | Italy | Referendum | 29.3 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 7 | Mali | Leg | 29.3 | Held | Strict | Autocracy |

| 8 | Armenia | Referendum | 5.4 | Postponed | Strict | Autocracy** |

| 9 | North Macedonia | Leg | 12.4 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 10 | Syria | Leg | 13.4 | Postponed | Moderate | Autocracy |

| 11 | Kiribati | Leg | 14.4 | Held | na | na |

| 12 | South Korea | Leg | 15.4 | Held | No | Democracy |

| 13 | Russia | Referendum | 22.4 | Postponed | Moderate | Autocracy |

| 14 | Sri Lanka | Leg | 25.4 | Postponed | Moderate | Democracy |

| 15 | Serbia | General | 26.4 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 16 | Chile | referendum | 26.4 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 17 | Bolivia | General | 3.5 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 18 | Poland | Exe | 10.5 | Still scheduled | Strict | Democracy |

| 19 | Dominican Republic | General | 17.5 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 20 | Switzerland | Referendum | 17.5 | Postponed | Strict | Democracy |

| 21 | Burundi | General | 20.5 | Still scheduled | Light | Autocracy |

| 22 | Iceland | Exe | June | Still scheduled | Light | Democracy |

| 23 | Mongolia | Leg | 24.6 | Still scheduled | Light | Democracy |

| 24 | Malawi | Exe | 2.7 | Still scheduled | Light | Autocracy |

| 25 | Singapore | General | 2020-21 | Unclear | Moderate | Autocracy |

| * Second round of elections postponed from 17th of April to 11th of September

** This is a V-Dem estimate, although the country is in the democratic transition. |

||||||

Sources: IDEA; V-Dem, and variety of media reports

Table 2. Election results

| # | Country | Elections | Date | vote share now | vote share before | turnout | Delta | Winner |

| 1 | Iran | Leg | 21.2 | 76.2 | 29 | 42.57 | 47.2 | Principlists |

| 2 | Israel | Leg | 2.3 | 29.46 | 25.1 | 71.5 | 4.36 | Likud |

| 3 | Guyana | General | 2.3 | 49.82 | 50.3 | 72.49 | -0.48 | APNU-AFC |

| 4 | Guinea | Leg+referendum | 22.3 | 88.94 | 46.26 | 58.24 | 42.68 | PRG |

| 5 | Mali | Leg | 29.3 | 19.83 | 29.4 | 35.58 | -9.57 | Rally for Mali |

| 6 | South Korea | Leg | 15.4 | 83.27 | 62.5 | 66.21 | 20.77 | Democratic Party/ Together Citizens |

NB! Vanuatu and Kiribati are dropped.

*Mali’s official results are not announced yet

Source: IDEA, and variety of media reports

Elections at the onset of the pandemic: downplaying the threat?

Iran exemplifies an autocracy that prioritized political survival over public health by downplaying the threat and the spread of coronavirus held parliamentary elections on 21st of February, without introducing any restrictive measures. High turnout at the elections was important for legitimising the regime that suffered from the November protests against the fuel price-strike by the authorities, which the state brutally suppressed, and from the armed conflict with the US, during which Iran mistakenly shot down the Ukrainian passenger plane, killing 176 on board. The turnout at the election on the 21st of February, nevertheless, was record low. The Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei accused Iran’s enemies of spreading negative propaganda about the coronavirus in order to dissuade Iranians from voting. Autocracies usually enjoy more of a leeway in meddling with electoral time-tables as they rarely prioritise electoral accountability over public safety as a common good.

However, electoral democracies also faced the dilemma of whether to hold elections or to postpone. In Poland, the state of emergency was not declared, and the country is already starting to lift the restrictions (despite passing the peak 3 days after announcing the gradual lifting). Six by-elections were organised on 22nd of March and the presidential election on the 10th of May is still being prepared, despite the criticism of the opposition that states that the ruling PiS party chooses elections over the health of the population. The incumbent president Duda, the candidate of the PiS at the 2015 election, is currently predicted to win elections in the first round. In both cases, countries introduced the quarantine measures with a significant delay. In the case of Iran, electoral victory is clearly at the public health’s expense.

Postponing the Constitutional Vote in Russia: An Untimely Virus

Six referendums – in Armenia, Chile, Guinea, Italy, Russia, and Switzerland – were to take place during the pandemic. In cases of Russia and Guinea – these are popular voting for the constitutional amendments that aim to extend the existing presidential terms. In Guinea, an overwhelming majority voted for the incumbent Alpha Conde – almost 92%. The amendments adopted will allow him to stay in power for another 12 years. The most dramatic point here is that Conde is a former leader of the opposition who had survived earlier military junta’s regime and in 2010 was the first democratically-elected president. In Russia, the constitutional vote is yet to come. However, the main goal is quite the same – to adopt the clauses that would extend Vladimir Putin’s presidential term until 2036 (in case he wishes to run for another re-elections). Although, technically speaking, this vote does not qualify for a referendum as its initiation does not conform with the existing federal law on referendums.

One may speculate that the social distancing and other movement restricting measures were not implemented in Russia until the last week of March because the authorities wanted to carry on with the Constitutional plebiscite until the very last moment. On 17th of March, Vladimir Putin had a meeting with the chair of the Central Election Commission (CEC) of Russia Ella Pamfilova, he mentioned that in the states where the epidemic situation was much worse, the elections were still held. On 25th of March the president signed a decree postponing the Constitutional referendum until later.

Carrying out the vote that is so heavily loaded with symbolic value for the current regime in mid-April, threatening the population and especially the elderly voters would give the upper hand to the opposition. On the other hand, the political support in the times of rallying around a natural threat usually boosts public support everywhere (e.g. look at the South Korean electoral results where the incumbent coalition won with a landslide victory). And there are grounds to believe that by midsummer the state of Russian economy deteriorates to the extent that the current support will start to fade away. For instance, the Vladikavkaz protests against the lockdown are not about COVID-dissidents, they are mainly about growing unemployment and insecurity.

From the regional perspective, the pandemic affects not only scheduled elections but might also bring about new elections. For instance, the head of the Komi Republic Sergey Gaplikov had to resign after there was a COVID-19 outbreak in the region in one of the hospitals. Vladimir Uiba, Doctor in Medical Sciences, has been appointed as the acting head, and the elections for the new head will be held on the 13th of September 2020.

The bottom line, when deciding upon coronavirus fighting strategies, the states have to take many things into account. The leaders, of course, care about their support and when national elections are at stake, their response to the coronavirus outbreak might be affected by it. There are more elections still scheduled for the second half-year of 2020, including the US presidential elections. More data are yet to come and to be analysed. However, we can already say that there are some patterns in how various regimes prioritize public health: in more accountable regimes restrictions are expected to be tougher, while less accountable regimes will try to balance between a crumbling economy and silencing the opposition.

3 Replies to “Electioneering in the times of pandemic: an overview of the elections and referendums from February to July 2020”