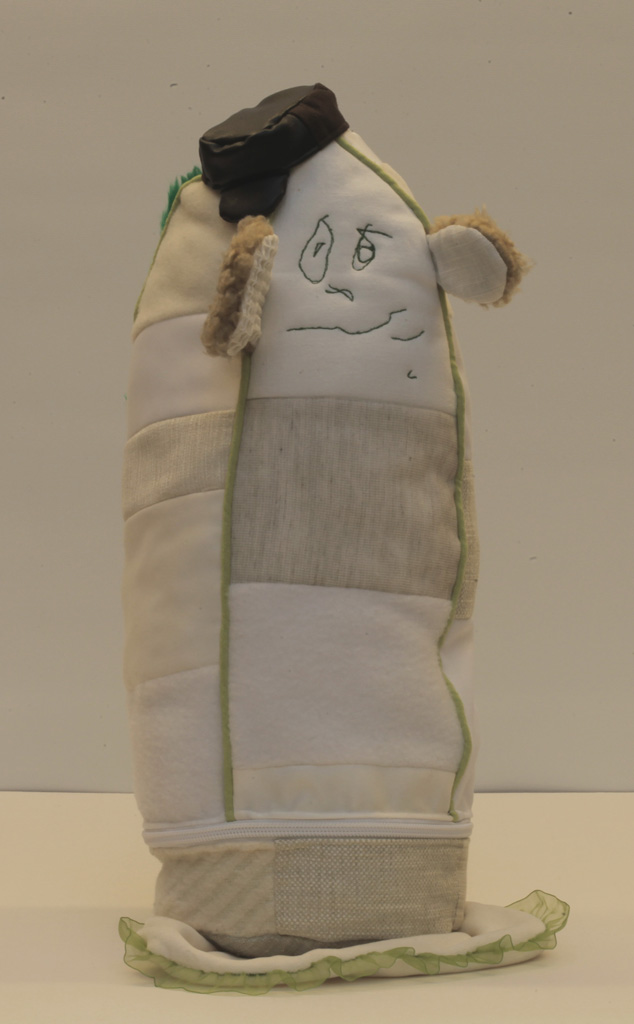

A soft toy called Unto Uolevi was acquired for the collections of Helsinki University Museum Flame from the discipline of craft teacher training at the Faculty of Educational Sciences. This soft toy has its origins in a drawing by a daycare-aged child. The toy was created in 2012 on a course on the basics of craft science given by Professor Pirita Seitamaa-Hakkarainen and University Lecturer Henna Lahti. Some of the students participated in a project where the process of craft design was investigated through the creation of stuffed toys. The different stages of Unto Uolevi were recorded in the museum collections: the drawing, a prototype, a trial run and the final version.