Easter greetings from the Helsinki University Museum! Our object of the month in April is a red Easter egg that is more than 100 years old. The egg used to belong to Eero Loimaranta, a Finnish medical doctor, who is said to have received it as a gift from Grand Duchess Maria of Russia during the First World War. The porcelain egg is 10 centimetres high. It has holes on the top and bottom of the shell, perhaps for hanging the egg on a string. The smooth porcelain surface is decorated with the Cyrillic characters X and B, or H and V when translated into the Latin alphabet. The egg came into the Helsinki University Museum’s possession as part of the collections of the museum of medical history.

Legends of saints and arts and crafts

In the Christian tradition, the egg is an ancient symbol associated with Easter denoting the miracle of Christ’s resurrection. According to a legend, Mary Magdalene gave the Roman Emperor Tiberius a red-coloured egg when preaching the Gospel. The colour red refers to the blood of Christ and is also the colour of joy and love. According to another version of the legend, Mary Magdalene gave an ordinary egg to Tiberius, who responded by saying that he did not believe Jesus could have risen from the dead, any more than the egg could turn red. Miraculously, the egg immediately began to turn red.

In the Orthodox Christian tradition, believers have long celebrated Easter by exchanging Easter eggs. When doing so, they kiss each other on the cheek, saying “Christ is risen” and responding with “He is truly risen”. This greeting is also referred to with the letters XB that frequently decorate the Easter eggs. The abbreviation stands for the Church Slavonic words Хрїстóсъ Bоскрéсе, Hristos Voskrese.

Easter was the biggest celebration of the year during the period of imperial Russia, as it is today for Orthodox Christians. The design and creation of Easter eggs made of wood, precious metals or ornamental minerals grew into a separate branch of arts and crafts in the 19th century. The beautifully moulded or decorated Easter greetings were highly valued as gifts offered in the form of both decorative objects and necklaces. Giving eggs was a common practice not only among friends, but also between the ruler and his subjects. For example, Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia, is known to have given 800 Easter eggs to his guests during an Easter celebration in 1902. It is said that his cheeks were stained black from the moustache dye of the guests after he had exchanged kisses with them.

The most famous Easter eggs produced during the period of the Russian Empire were created by Carl Fabergé for the imperial family to give as gifts. Alexander III of Russia commissioned a gold and enamel egg for his wife in 1885. Eggs commissioned from Fabergé soon became a tradition within the imperial family. Before the Russian Revolution, designers and jewellers working for Fabergé, many of whom were Finns, produced 50 imperial eggs. During the revolution, some of the eggs disappeared and others were sold by the Soviet government to buyers abroad. Today, these goldsmith masterpieces sell for high prices at auctions and draw large crowds to museums. One of the eggs, the Mosaic Egg, designed and manufactured by the Finns Alma Pihl and Albert Holmström under the supervision of Fabergé in 1914, has ended up in the collections of Queen Elizabeth II.

Doctor and soldier

The red Easter egg presented this month was previously owned by Eero Loimaranta, born in 1890 in Huittinen in southwestern Finland as the youngest child of rural dean Wilhelm Lindstedt and Hilma Nyholm, a vicar’s daughter. After graduating from upper secondary school, Loimaranta began to study medicine at the Imperial Alexander University, now the University of Helsinki. He completed an undergraduate degree in medicine in 1911 and went on to work as an assistant at the University’s department of anatomy, but abandoned this position during the First World War to work as a military doctor. A Finnish association for treating soldiers who had been wounded and become ill, later the Finnish Red Cross, equipped two field hospitals, called ‘ambulances’, for the Eastern Front. Loimaranta accompanied one of these ambulances, funded by a group of Finnish industrialists, to Daugavpils and Warsaw, for instance.

With the Russian Revolution and Finland’s declaration of independence, Loimaranta returned to his native country and enthusiastically joined the White Guard, a voluntary militia. During the Finnish Civil War of 1918, Loimaranta fought for the non-socialist Whites as a machine gunner, for example, in the bloody battle of Sampakoski. After the war, he remained in the service of the army, now as a doctor. However, his military career and further studies in medicine came to an abrupt end when he died of a heart attack at the age of just 29 on 24 May 1919.

An imperial gift

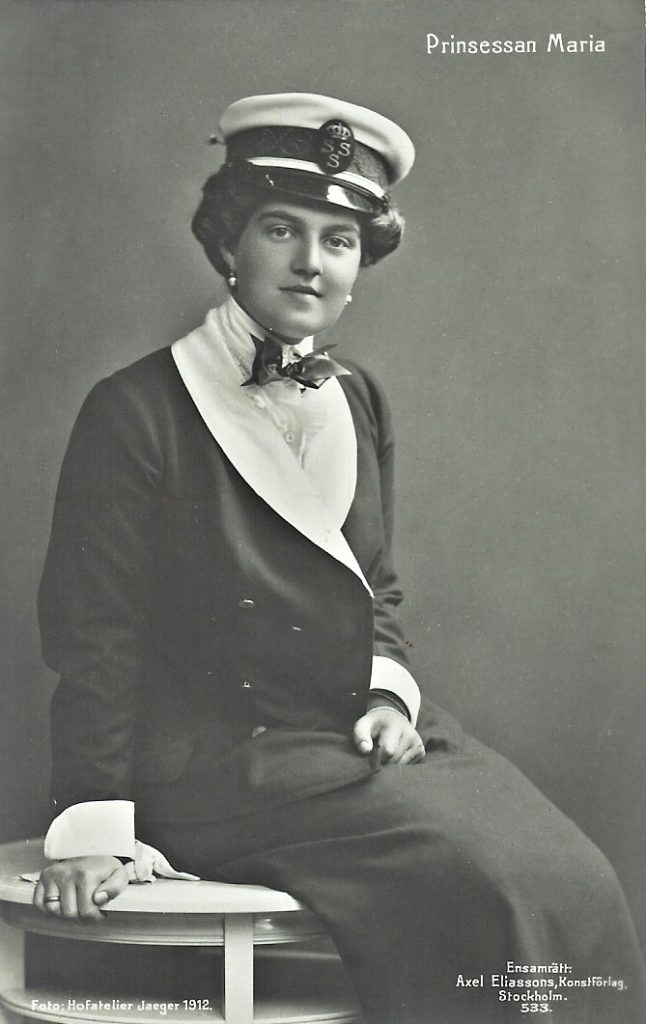

Loimaranta received the Easter egg when serving at the front during the First World War, apparently from Grand Duchess Maria. More specifically, it is thought that the egg was given to him by Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger, who was born in 1890 and was a granddaughter of Alexander II and a cousin of Nicholas II.

In 1908 she married Prince Wilhelm of Sweden, the brother of the current King Carl XVI Gustaf’s grandfather, the younger son of King Gustaf V. In 1909 the couple had a son, Lennart Bernadotte, but their marriage ended in divorce in 1914. Maria later married the Russian Sergei Mikhailovich Putyatin with whom she had a son, who died at the age of just one. Maria survived the Russian Revolution by escaping the country in summer 1918 through Ukraine and Romania to Paris, where she opened an embroidering fashion atelier. In the 1920s Maria divorced her second husband and emigrated to the United States, where she worked as a journalist and photographer and wrote her memoirs. She moved to Argentina during the Second World War, but later returned to Europe and died in West Germany in 1958.

During the First World War, Grand Duchess Maria served as a volunteer nurse on the Eastern Front. According to wartime newspapers, she visited the Finnish ambulance stationed there at least twice, in September 1915 and October 1916. According to the chief physician of the ambulance, Axel Fredrik Hornborg, Grand Duchess Maria found the Finnish hospital comfortable and pleasant: “She was particularly taken with the decor […] as well as the bandaging and operating rooms, the X-ray cabinet, the meals and bookkeeping.” For their part, the doctors and nurses were delighted when the grand duchess invited them to tea, chatting cosily with them in Swedish. Perhaps she wished to not only visit the medical staff, but also to give them Easter gifts that would bring them joy during the harsh realities of war.

Katariina Pehkonen, curator

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

Sources:

Aamulehti, 3 October 1915

Helsingin Sanomat, 2 October 1915 and 27 May 1919

Turun Sanomat, 9 November 1916

Oleg A. Fabergé: Muistikuvia. Tammi, 1990

Tatjana Muntjan: “Venäläinen pääsiäinen”, in Fabergén aika. Tampereen museoiden julkaisuja, 2006

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm: Fabergé ja hänen suomalaiset mestarinsa. Tammi, 2008

Vuokko Nissinen: “Ortodoksien suurin juhla on pääsiäinen, johon valmistaudutaan koristelemalla munia.” Savon Sanomat, 27 March 2016: https://www.savonsanomat.fi/paikalliset/3053193, accessed 27 January 2021

Pekka Söderlund: “Kyllä sieltä se lääkäri löytyi.” Kankaanpään Seutu, 15 February 2018: https://www.kankaanpaanseutu.fi/puheenvuoro/art-2000006732745.html, accessed 10 January 2021

“Suomen Punaisen Ristin historiaa 1910-luvulta”: https://www.punainenristi.fi/tyomme/historia/1910-luku/, accessed 27 January 2021

Information on Maria Pavlovna the Younger on the Historiska personer website: http://historiska-personer.nu/min-s/p8e51359b.html, accessed 27 January 2021

The Bernadotte Dynasty: https://www.kungahuset.se/royalcourt/royalfamily/thebernadottedynasty.4.396160511584257f218000814.html, accessed 23 February 2021

Information on the Mosaic Egg on the website of the Royal Collection Trust: https://www.rct.uk/collection/9022/the-mosaic-egg-and-surprise, accessed 27 January 2021