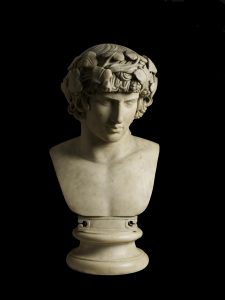

A handsome young man with curly hair stands in a corridor on the fourth floor of the University of Helsinki Main Building. He is naked and leaning his weight on one of his legs. His eyes are downcast and his expression is sombre and slightly melancholy. Is he Antinous?

A sculpture known as Antinous is a plaster cast of an ancient marble sculpture. Antinous was a real person who lived a short and tragic life in the 1st century CE. Exploring the history of the statue takes us on a journey to the dark side of humanity, the world of archaeology as well as achievement in art and art conservation.

The statue is part of the University’s collection of plaster sculptures, which are on display in the Main Building and other locations. The Senate Square side of the Main Building, also known as the old side, was recently renovated, and works of art displayed there were conserved and restored. For further information on the renovation and conservation project in Finnish, please see the University’s blog Päärakennuksen peruskorjaus. The Helsinki University Museum carried out the conservation of the sculptures, and some of its specialists were also involved in the renovation project.

“Antinous” stands on a plinth next to the Resting Satyr on the left and Hermes and the Infant Dionysus on the right. The statue of “Antinous” is approximately life-size: its height, including the plinth, is 187 cm. The original marble sculpture is part of the collection of the Capitoline Museums of Rome, and has been dated to c. 130–150. The plaster cast owned by the University of Helsinki was purchased from the Louvre in Paris in 1875, when the museum sold plaster casts of famous sculptures.

At the time, a collection of plaster sculptures was being established for the University of Helsinki, or the Imperial Alexander University as it was then known. The accumulation of the collection commenced in 1843 with funds collected from the public by students. Copies of both ancient and Renaissance sculptures were purchased. The purpose was to follow the example of many other European universities by establishing a collection of well-known sculptures that would vitalise teaching in art history and history as well as otherwise contribute to the general education and edification of the community. The sculptures have since been displayed in various locations, including the University’s Art Room and the Arppeanum building, but they are usually associated with the Main Building, whose corridors they have graced for a long time. The collection was long held by the discipline of art history and is, in fact, known as the art-historical sculpture collection. It was brought under the administration of the Helsinki University Museum in 2014.

Anatomy of a plaster sculpture

The statue of “Antinous” has visible joints in the pelvis, neck and arms because it is composed of five detachable parts. When using the plaster cast method, it is easier to cast the pieces separately and then put them together. In the 19th century, the sculptor Carl Eneas Sjöstrand (1828–1906) assembled and put the finishing touches on the sculptures at the University.

It is also easier to transport sculptures in pieces. Some of the joints are fitted together with plaster holding pins, and others with metal structures inside the plaster that are joined together by locking pins. “Antinous” was, in fact, recently disassembled when it was conserved together with many other works included in the collection of plaster sculptures.

The condition of the works in the University’s collection of plaster sculptures was surveyed in 2018 when it became known that a renovation would soon begin in the Main Building and the sculptures would have to be moved elsewhere. The survey of “Antinous” uncovered no major structural damage, but some joints were broken and required repairs. The surface of the statue also required thorough cleaning, partly due to old repairs and varnishing that had slightly changed colour over the years, making the statue appear tarnished. Small cracks were also discovered.

“Antinous” was one of the first pieces in the collection to be conserved. It was selected for a project involving the use of experimental conservation techniques in November 2019 to obtain detailed information on previous surface coatings and repairs. The purpose was to establish how the sculptures could be conserved. The conservation work took place at the Finnish Heritage Agency’s Collections and Conservation Centre in Vantaa, where the Helsinki University Museum rented facilities.

Conservators Anna Lehtinen and Sari Pouta of the conservation company Konservointipalvelu Löytö examined “Antinous” and conserved it. Any dirt found was removed, varnishes that had changed colour were removed, and differences in tone were evened out. The original colour patina was not removed.

Indeed, the patina is the reason why a quick glance reveals no major differences between the ‘before’ and ‘after’ photos above. In fact, the sculpture is not supposed to be bright white the way in which its marble model now is. Brown tones were originally used to imitate the colours of the marble sculpture when it was discovered by archaeologists.

“Antinous’s” hair is actually slightly darker after the most recent conservation. This is due to the fact many previous repairers who have handled the sculpture considered the whiteness of plaster sculptures as an ideal. They were keen to make the sculpture whiter with various coatings. When these previous alterations and repairs were now removed, the original remaining tones emerged just as they had been when created by a plaster sculpture workshop in the 19th century. Original classical sculptures were painted, but usually only small pigment particles remain of the paints used.

“Antinous” may look quite similar to what he looked like before the conservation, but the modern conservation methods used will help it stand the test of time. Correctly chosen substances do not damage the sculpture even over a long period of time; in addition, these substances no longer allow dust and dirt to have access to the porous plaster surface.

“Antinous”, like many other plaster sculptures in our collection, was moved back to the University’s Main Building in early summer 2021 when the renovation of the old side of the building was close to completion. The doors of the University buildings opened to the public at the beginning of the new academic year in early September, and visitors can now view the sculptures again. However, the statue of “Antinous” was presented to the public slightly earlier when it was showcased at the Ateneum Art Museum’s exhibition ‘Inspiration – Contemporary Art & Classics’ from 18 June to 20 September 2020, together with three other works on loan from the University’s art collections.

A well-known, yet mysterious figure

Antinous or Antinoös (c. 111–130) was a well-known favourite of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (76–138). According to ancient historians, such as Pausanias (c. 110–180) and Cassius Dio (c. 155–235), Antinous was born in Bithynium (later Claudiopolis) in Asia Minor on the coast of the Black Sea. Hadrian met the young boy when travelling in the area in 123. Antinous joined Hadrian’s entourage, possibly to become an imperial servant. Hadrian is said to have been infatuated with not only Antinous’s beauty, but also his sharp wit. Hadrian had a wife, Sabina, but the marriage was apparently unhappy, and the Emperor was also said to favour men in his romantic relationships. The infatuation between Hadrian and Antinous was described as reciprocal and, startlingly, even modern historians call the two ‘lovers’, although, of course, their relationship could not be called equal by any stretch of the imagination. After all, Antinous was just 12 years old when they met, whereas Hadrian was a grown man who wielded absolute power in his capacity as Emperor.

According to ancient written sources, Antinous moved to the Emperor’s villa in Tibur (now Tivoli) no later than 125. The Emperor travelled extensively with his retinue. One of the reasons was apparently that not all Romans took a favourable view of Hadrian’s relationship with the young boy, although such relationships were not uncommon in ancient Rome. The basis was a teacher-student relationship between an older man and a young boy, but sexual relations were also occasionally involved. Antinous often accompanied Hadrian on his travels and, among other things, the two hunted together.

In 130 Hadrian, Antinous and their entourage arrived in Egypt. There, Antinous drowned in the Nile, at the age of just under 20. It is not known whether his drowning was intentional, accidental or even homicide. Speculation has been rife since ancient times.

Crushed by grief, Hadrian deified his beloved and founded the city of Antinoöpolis in Egypt in his memory. Several statues of Antinous were erected in the city, and celebrations were held to commemorate him. Coins were also struck with the image of Antinous. So far, it has been discovered more than a hundred statues as well as coins in large quantities. The deity Antinous was associated with features of the Egyptian god Osiris and the Roman god Dionysus, and he became the object of a fairly popular cult. This cult remained prominent until the end of the fourth century when it was banned as Christianity spread.

After Antinous’s body was found in the Nile, Hadrian had it delivered to Rome, where Antinous was buried in a spectacular tomb on the site of Hadrian’s Villa, or the Villa Adriana. Statues of Antinous were also erected on the site. After Hadrian, the villa was used by his successors, but during the time of Constantine the Great, who was Emperor of Rome between 306 and 337, the site was abandoned and fell into ruin. Constantine the Great had many of the sculptures located in the villa delivered to Constantinople, with the rest remaining on the villa site at the mercy of the weather and looters. It was not until excavations began on the site in the 18th century that the remaining works were discovered. Among the works uncovered were statues of Antinous.

A great deal of damage occurred before the villa site itself was protected in the 19th century. The site, which now accommodates some 30 buildings, was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1999, but still remains unexplored in many places.

Very little is known about Antinous. However, Antinous’s tragically short life has fascinated many people throughout the ages. In Finland, the author Volter Kilpi (1874–1939) wrote a book of lyrical prose about him (Antinous, 1903).

What did Antinous actually look like?

Professor Caroline Vout of Cambridge University writes in her article “Antinous, Archaeology and History” that Antinous is one of the most recognisable figures of ancient sculptures. She wonders whether the fascination with Antinous is due precisely to the fact that while so many statues of him have been found, so little is known about his life.

Sculptures identified as Antinous have been divided to types. The statues found as well as other objects associated with Antinous have been investigated by, among others, Professor Emeritus Hugo Meyer of Princeton University, who published a comprehensive catalogue of these objects in 1991.

Ancient sculptures identified as Antinous have been divided into various types. The statues found as well as other objects associated with Antinous have been investigated by, among others, Professor Emeritus Hugo Meyer of Princeton University, who published a comprehensive catalogue of these objects in 1991. One of the best known types of Antinous sculptures is the Farnese Antinous, which represents the main type of Antinous sculptures in terms of face, hair and torso. The original version of the Antinous sculpture in the collections of the University of Helsinki is known as the Capitoline Antinous. It has shorter, curly hair, and its facial features differ slightly from those of the Farnese Antinous, but the torso and the angle of the head are similar. The arms of the Farnese Antinous have been restored and are therefore reminiscent of the arms of the Capitoline Antinous.

The original Capitoline Antinous sculpture can now be found in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The marble sculpture was found apparently near the Hadrian’s Villa during excavations carried out in 1732. Pope Clement XII purchased the sculpture the same year, and it was placed in its current location in the Capitoline Museums. The left arm and leg of the sculpture had been broken off and gone missing over the years, but the sculptor Pietro Bracci (1700–1773) restored them in their supposed position. The French looted the sculpture in 1797 and took it with them to France, but the sculpture was returned to Rome in 1815.

Other types of Antinous sculptures include what are known as the Egyptian Antinous and the Antinous Mondragone. The Egyptian Antinous is wearing the headdress of an Egyptian pharaoh. The Vatican Museums, for example, have one such marble sculpture in its collections, found on the site of Hadrian’s Villa. The Mondragone type takes its name from the head of the colossal sculpture now located in the Louvre, which was part of the Borghese family collection in the 18th century and kept in the family’s Villa Mondragone. The sculpture depicts Antinous with a hairstyle seen in statues representing the gods Dionysus and Apollo. Representatives of the main type of Antinous sculptures have also occasionally been depicted with an ivy wreath adorning their locks. The wreath refers to the god Dionysus, whose symbol it was.

But does the statue of “Antinous” in our sculpture collection even depict Antinous? More recent research in the 20th and 21st centuries has confirmed the idea that the sculpture known as the Capitoline Antinous may not be an image of Antinous at all, but rather possibly a Roman copy of a Greek sculpture originally depicting Hermes. The facial features of the sculpture differ from those of sculptures generally acknowledged as representing Antinous.

However, an even more significant distinguishing feature is the short hairstyle with its small curls, which clearly differs from the swirling shock of hair that covers the neck of the Antinous sculptures. According to legend, the god Hermes was the messenger of the gods. In art, Hermes has been variously depicted as an athletic youth, a man with winged sandals and a staff, and (in early Greek art) an elderly man with a beard. The Capitoline Museums, the owner of the statue of Antinous, has, in fact, re-named the statue ‘Hermes-Antinous’. The retention of the name ‘Antinous’ alongside Hermes can be justified by the fact that the name has been historically well-established in connection with the sculpture. In addition, the popular figure of Antinous influenced sculpture in Hadrian’s time, and it is possible that the appearance of the Capitoline sculpture, which has puzzled scholars, is due to the transfer of Antinous’ features to sculptures depicting other young men, including Hermes.

Of course, we cannot know what Antinous, who lived in the second century, actually looked like, but the beautiful, curly-haired young man of the sculptures has preserved his memory for over a thousand years. The Finnish author Volter Kilpi has imagined Antinous’s thoughts:

“. . . life is about moments of beautiful existence. . .”

Those words reverberate in trembling Antinous’s mind like gentle light spreading through each vein. Life is about moments of beautiful existence! Beautiful existence flows like a hand caressing, forming a man, stroking and melting each of his limbs into a swell of beauty, and turning his entire being into a soul. Beautiful moments are like an exquisite vibration that permeates a man.

(Volter Kilpi: Antinous, 1913; unofficial translation from the Finnish original)

Anna Luhtala, curator

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

Sources and literature:

“Albani Hermes-Antinous”. Capitoline Museums. http://capitolini.info/scu00741/?lang=en (accessed on 9 September 2021)

Castrén, Paavo & Pietilä-Castrén, Leena 2000. Antiikin käsikirja. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava

Fleming, James 2019. The Image of Antinous and Imperial Ideology. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s degree in Classical Studies, Department of Classical Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Ottawa

Hakanen, Ville. Announcement 5.11.2021.

“Hadrian: An emperor’s love”. British Museum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AvdXNuNeqP4&t=54s (accessed on 9 September 2021)

Jones, Christopher P. 2010. New Heroes in Antiquity – From Achilles to Antinoos. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press

Kilpi, Volter 1903. Antinous. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava

Luhtala, Anna 2020. “Yliopiston kipsiveistoskokoelman historia ja konservointi”. Article in the blog ‘Päärakennuksen peruskorjaus – kohti moderneja oppimistiloja historiaa kunnioittaen’. https://blogs.helsinki.fi/paarakennuksen-peruskorjaus/2020/11/10/yliopiston-kipsiveistoskokoelman-historia-ja-konservointi (accessed on 10 September 2021)

Mark, Joshua J. 2021. “Antinous”. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/antinous (accessed on 9 September 2021)

Matyszak, Philip & Berry, Joanne 2008. “Antinous”. Lives of the Romans. London: Thames & Hudson

Meyer, Hugo 1991. Antinoos: Die archäologischen Denkmäler unter Einbeziehung des numismatischen und epigraphischen Materials sowie der literarischen Nachrichten: Ein Beitrag zur Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte der hadrianisch-frühantoninischen Zeit. American Journal of Archaeology, 1994-04-01, Vol. 98 (2), pp. 377–378

Nikula, Riitta 1974. “Helsingin yliopiston veistokuvakokoelman historiaa ja taustaa”. In Helsingin yliopiston taidehistorian laitoksen julkaisuja 1. Ed. Lars Pettersson. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, Department of Art History

“Statue of ‘Capitoline Antinous’”. Capitoline Museums. http://www.museicapitolini.org/en/percorsi/percorsi_per_sale/palazzo_nuovo/sala_del_gladiatore/statua_dell_antinoo_capitolino (accessed on 8 September 2021)

“Statue of Osiris-Antinous”. Vatican Museums. https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-gregoriano-egizio/sala-iii–ricostruzione-del-serapeo-del-canopo-di-villa-adriana/statua-di-osiri-antinoo.html (accessed on 9 September 2021)

“Villa Adriana (Tivoli)”. UNESCO, World Heritage Center. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/907 (accessed on 9 September 2021)

Vout, Caroline 2005. “Antinous, Archaeology and History”. The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 95 (2005), pp. 80–96. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies