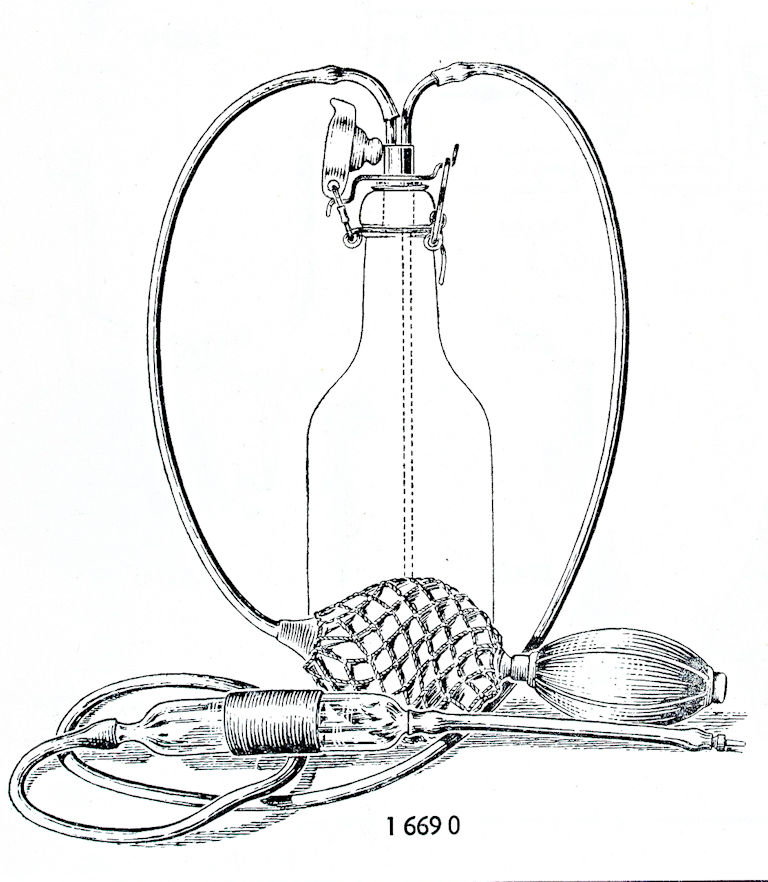

This time our object of the month is a soda bottle. It has never contained a beverage, however. It has been used to store and transport blood for transfusions. In addition to a flip-top bottle, the set includes a needle, a rubber bulb syringe, and a metal cannula that branches into two detachable rubber tubes. Unfortunately, as is often the case with old objects, the rubber parts are perished and in quite bad condition.

Transfusion experiments with animal blood

The importance of blood has been understood even when its actual function within the human body and the very existence of the circulatory system were still unknown. Blood was believed to be one of the four vital fluids in the humoral theory, a school of thought developed by the Ancient Greeks. Instead of giving a blood transfusion to a sick or injured person, the cure was to get rid of the so-called bad blood by bloodletting, for example.

It was only during the seventeenth century that instead of removing blood, it was transferred into humans or animals. The rise in experimentation can be attributed to an English physician, William Harvey (1578-1657), and his discovery of the principles of the circulatory system and the function of the heart. Mere theory was not enough to ensure successful blood transfusions; syringes needed to be developed. The first syringes suitable for intravascular injections were developed a few years after Harvey’s findings.

The problem with syringes for transfusions was that blood coagulates very quickly. It is possible that the experiments led to fewer adverse effects due to the comparatively small amounts of blood that were transfused. Soon after, so-called direct transfusions became common, where instead of using the syringe, blood was transferred through a tube from the donor’s artery to the recipient’s vein. In this way, it was possible to transfer larger volumes of blood. However, direct transfusions led to inexplicable complications and higher mortality rates.

To us, these first experiments with transfusion sound frankly unhinged. For instance, people might have been given the blood from a dog or a sheep. Meanwhile, animals were subjected to even more bizarre experiments: they were injected with other liquids such as wine and beer.

Slow progress

Gradually, transfusions from one person to another became more common in the nineteenth century. During the same period, the procedures were increasingly performed by trained doctors rather than barber surgeons. Rapid coagulation was still a problem in search of a solution. The defibrination of blood was helpful to some extent. This is the process wherein the protein (fibrin) causing the coagulation is separated from the blood. However, it was a difficult and time-consuming process. At the end of the century it was discovered that adding sodium citrate to blood binds calcium, preventing coagulation. Later, adding glucose was also found to be beneficial, as it helps to preserve the red blood cells following a transfusion.

Although transfusions from animals to people were no longer performed and the technique for transferring blood had improved in many ways, the procedure still led to deaths that seemed hard to explain. Many doctors believed that the blood of close relatives was the most suitable for transfusions. This theory was confirmed, and the fatalities were explained when, at the turn of the twentieth century, it was discovered that there are several blood types. Ascertaining the blood type of donor and recipient and their compatibility made blood transfusions much safer.

Direct transfusion was also still used in the early twentieth century. In addition to being technically challenging, both the donor and the recipient needed to be physically present during the procedure. In Finland, the first direct transfusion was performed in 1913 by Richard Faltin, a leading surgeon.

The beginning of blood transfusion services in Finland

By the end of the First World War, other countries had already had good experiences with blood banks, whereas in Finland, progress was slow. Typically, medical students or the patient’s relatives gave blood when the need arose, and little or no attempt was made to store blood.

In 1935, a blood transfusion service was initiated by the Finnish Scouts. The practical arrangements were overseen by the Finnish Red Cross and the donor pool consisted of several hundred members. They were older scouts, who donated blood in various hospitals via direct transfusions. With the outbreak of the Winter War in 1939, the demand for blood increased, which led to the Finnish Defence Forces setting up a second blood donation service. Soon after the war began, bottles — like our object of the month — began to serve as vessels for storing and transporting citrate-infused blood. However, the bottle in itself was not enough; cold storage and insulated transport boxes were needed. After all, blood had to be stored at a temperature between +2 and +6 degrees Celsius and carefully warmed up before use. Of course, a great many donors needed to come forward.

The blood donation centres operated in conjunction with large hospitals. There were about twenty centres in total, and they were run by nurses and dentists. Volunteer blood donors numbered in the tens of thousands, some 80 percent of them women.

The blood service units in wartime field hospitals usually consisted of a trained member of Lotta Svärd, a Finnish paramilitary organisation for women, and a driver. The Lotta was responsible for making sure that enough blood and blood plasma was available. The blood was transported from the donation centres to field hospitals according to demand. As the need was hard to predict, and the blood could only be preserved for a few days, the unit had to be on constant standby.

Even though storing the bottles of blood and transporting them was difficult in such circumstances, it was still preferred to carrying out direct transfusions. During the Winter and Continuation Wars (1939-40 and 1941-44), approximately 190,000 bottles of blood were donated, while only about 1,700 direct transfusions were performed.

The University Museum’s blood transfusion apparatus

Nowadays we use blood bags instead of glass bottles when carrying out transfusions. Quite simply, they are lighter, easier to transport, and less fragile. However, in its time, the use of blood transfusion apparatus comprising glass bottles with flip-top caps represented a significant upgrade, and it greatly improved both blood donation and the transportation of blood in even the most challenging of circumstances.

Our object of the month was originally donated to the Museum’s collection in the 1960s. The brittle rubber parts have perished but originally there were two rubber tubes forking from the bottle, one with a needle at the end, the other with a rubber bulb syringe. By pressing the bulb, the citrate blood in the bottle was pumped into the patient’s vein via the tube and the needle.

The University Museum’s blood transfusion apparatus has been used for a blood transfusion in Tornio’s central hospital in the far north. We do not know who administered the blood transfusion or to whom it was given. However, it is quite possible that someone’s life was saved thanks to this very bottle and the life-giving fluid of its contents.

Susanna Hakkarainen, project planning officer

The blog was translated by Miila Karjalainen, Max Lainema, Nea Nieminen, Miro Palokallio, Noora Suominen, Janita Tuomainen, and Atte Virtanen, English undergraduates in the Department of Languages, under the supervision of John Calton, lecturer in English.

Sources:

Klemola, J. K. 1971: Kenttäsairaalan lääkäri. Hämeenlinna.

Lääkintävälinekuvasto. Instrumentarium. Helsinki 1948.

Rosén, Gunnar 1977: Sata sodan ja rauhan vuotta. Suomen Punainen Risti 1877-1977. Helsinki.

Suomen sotien 1939-1945 lääkintähuolto kuvina. Sotilaslääkinnän Tuki Oy. Hämeenlinna 1990.

Vartiainen, Terttu 1988: Kenttäsairaala jatkosodassa. Helsinki.

Arno Forsiuksen kotisivut: https://phtutkimusseura.fi/a-forsius/index.html