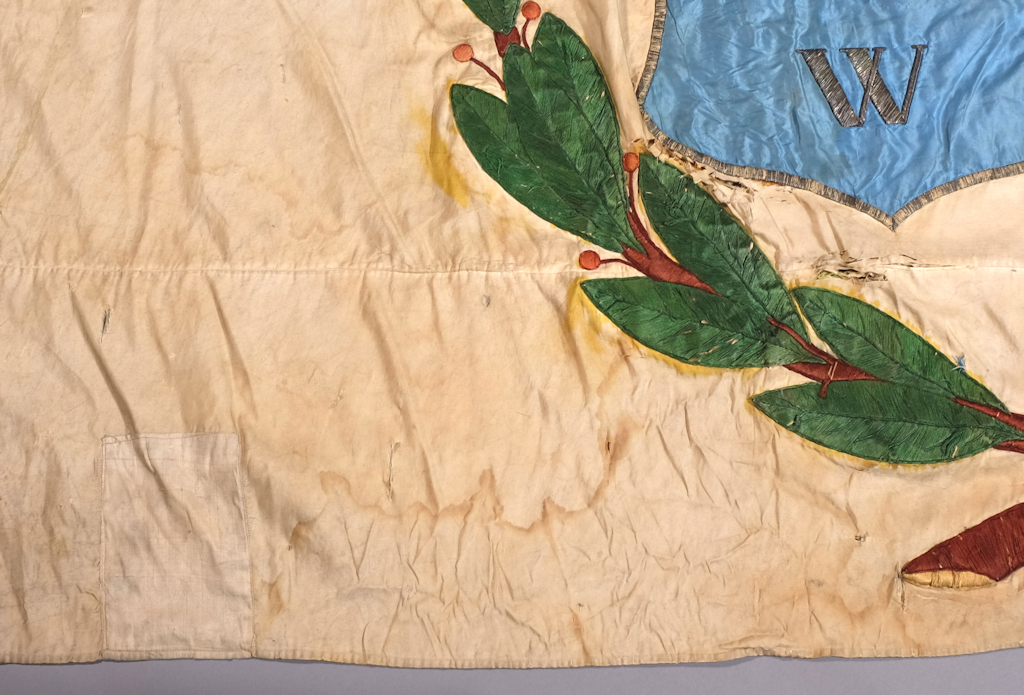

On the table lies a fragile silk flag. It is the first flag of the Wiipurilainen Osakunta, the student association, or ‘nation’, representing the Vyborg region, and it is full of symbolism. So full in fact that the flag had been banned before work on it had even begun, resulting in the postponement of its completion by several years.

Flag fever

The student nations of the Imperial Alexander University (the present-day University of Helsinki) were disbanded in 1852. The mid-century was a turbulent time in Europe, with revolutions breaking out in several countries. It was feared that the spirit of rebellion would spread to Finland through the students and in particular their nations. Despite being shut down, many nations continued their activities unofficially until they were legalized again on 26 March 1868. At the time there were six nations, among them Wiipurilainen Osakunta (the Student Nation of Vyborg).

After the student nations were legalized, there was enthusiasm among the students to design flags for their nations. The flags were made by women from each province. There was even talk of “flag fever”. Natalia Indrenius was the leader of the flag sewing for Vyborg. Her husband, Bernhard Indrenius, was the deputy chancellor of the university between 1866 and 1869. Somewhat ironically, Indrenius had previously been depicted in a cartoon that was published in the nation’s magazine. In the cartoon, Indrenius is shown tearing the students’ flag to shreds with the help of the university’s rector, Adolf Edvard Arppe.

This flag fervour was not viewed favourably in Saint Petersburg. The use of flags was banned in the spring of 1869, evidently before this flag could even be finished. The student nation had to wait years for their flag, but eventually it was completed in 1876. Again, the women of Vyborg were on the case, and this time the work was led by Ida Zilliacus, whose spouse Henrik Wilhelm Zilliacus was the nation’s inspehtori (‘inspector’). Thus, the student nation finally got its flag.

The use of flags

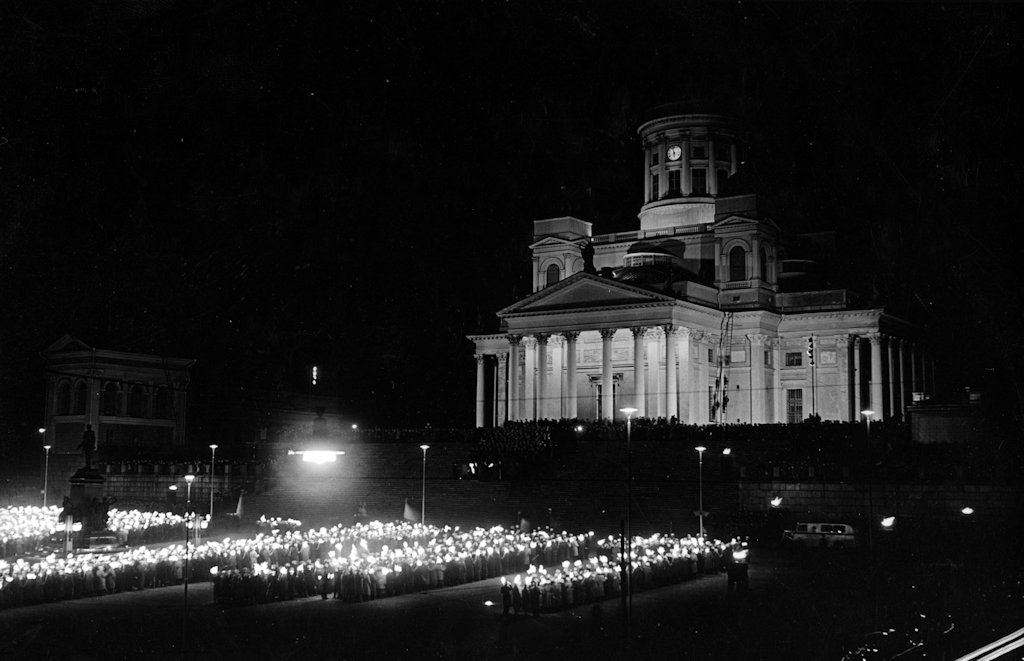

Student nations’ flags have been used from the very beginning at important events, be it a demonstration, an honorary visit, a celebration by the student nation or a degree ceremony. During Finland’s period of independence, student association flags have been a familiar sight, when celebrating Independence Day, for example. Students organised the very first Independence Day torchlight procession in 1951, following the death of Carl Gustav Emil Mannerheim, Marshal of Finland. On that occasion, student unions from all the Helsinki institutions of higher education joined the procession. There were some 2,000 participants along with thousands of spectators. After placing a wreath on Mannerheim’s grave at the Hietaniemi cemetery, the procession continued to the Senate Square where speeches and song recitals followed.

Damage to the flag tells its story

The flag is made of cream-coloured silk which, over the course of 145 years, has changed into a light brownish colour, partly due to the ageing of the fabric and the accumulation of surface dirt, and partly due to discolouration from nicotine. The flag still smells of tobacco; smoking was a part of everyday life in the nations up until recent decades.

The silk fabric has deteriorated and has torn, especially around the stitching. The emblems have been partly embroidered with metal thread and there are several layers of cardboard between the backing fabric and the fabric forming the emblems. As a result, the embroidery and the emblems in the flag are much heavier than the ground fabric, hence the tears around the embroidery. At the end of the 19th century, it was customary to add metallic salts to silk to increase the weight of the fabric, because the price of silk was determined by weight. Silk’s tensile strength decreases with age and weighted silk is more brittle than unweighted silk. It is possible that the silk used by the Wiipurilainen Osakunta in their flag is weighted, but probably to a relatively small extent or with substances that have not completely shattered the silk.

On the upper hoist side, i.e. where the flag would have been attached, there are dark streaks suggesting that the flag had been on display for lengthy periods of time. When the flag hung from a pole, the creases were not exposed to sunlight and the silk in those places has not darkened. The silk in the upper corner of the flag has been subjected to the greatest stress in use, and this is evidenced by the tearing.

The flag also shows discolouration caused by moisture, the “bleeding” of textile dyes, together with water stains. The materials used for the flag were doubtless originally selected to withstand light drizzle in outdoor use, but the lowered pH of the ageing textile material may have caused the dyes to become water-soluble. Of course, a more entertaining thought is that the stains were caused by a celebratory drink spilled on the flag in the heat of a student party, but humidity seems the more likely culprit.

The flag is fragile now and, with its stains and tears, looks in poor condition. But if the flag is to be conserved in the future, it is important that these valuable indications of use are not removed.

How the flag ended up in the University Museum’s collections

As museum artefacts, the flags are treated with the utmost care, but for the student nations they were objects to be used. This shows – as indeed it should. Naturally this also means that the flags have a finite lifespan. The Wiipurilainen Osakunta has had various flags. In the first Independence Day torchlight procession, the nation apparently used their second oldest flag. Both flags were donated to the collections of the University of Helsinki Museum in the 1980s. Today, the flags are considered to be the crown jewels of the Museum’s collections’.

Susanna Hakkarainen, project planning officer

Anni Tuominen, conservator

Translated by Jonna Alahautala, Diana Belozjorova, Anna Hakala, Miia Hankonen, Joona Juselius, Miro Jääskeläinen, Elisa Kari, Elli Kähkönen, Okko Länsikunnas, Sebastian Sihvola, Kaung Thein and Henni Veikkonen under the supervision of John Calton, lecturer in English.

Sources:

Kaukomieli XVII. Ylioppilaselämää – Wiipurilainen Osakunta 1653-2003.

Helsinki 2003. [‘Kaukomieli vol 17 Student life. Wiipurilainen Osakunta 1653-2003’]

Klinge, Matti 1978: Kansalaismielen synty. Ylioppilaskunnan historia 1853-1871. Vaasa. [‘The national awakening. A history of the student organisation, 1853-1871’]

Kolbe, Laura 1993: Sivistyneistön rooli. Helsingin yliopiston ylioppilaskunta 1944-1959. Keuruu. [‘The role of the educators. The University of Helsinki’s student organisation, 1944-1959’

Teperi, Jouko 1988: Henkinen taistelu Karjalasta autonomian ajan lopulla. Viipurilainen osakunta 1868-1917. Lappeenranta. [‘The struggle for Karelia at the end of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. Viipurilainen Osakunta, 1868-1917’]

TIMÁR-BALÁZSY, A., & EASTOP, D. (2002). Chemical principles of textile conservation. Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann.

MAREI HACKE (2008) Weighted silk: history, analysis and conservation, Studies in Conservation, 53: sup2, 3-15, DOI: 10.1179/sic.2008.53.Supplement-2.3