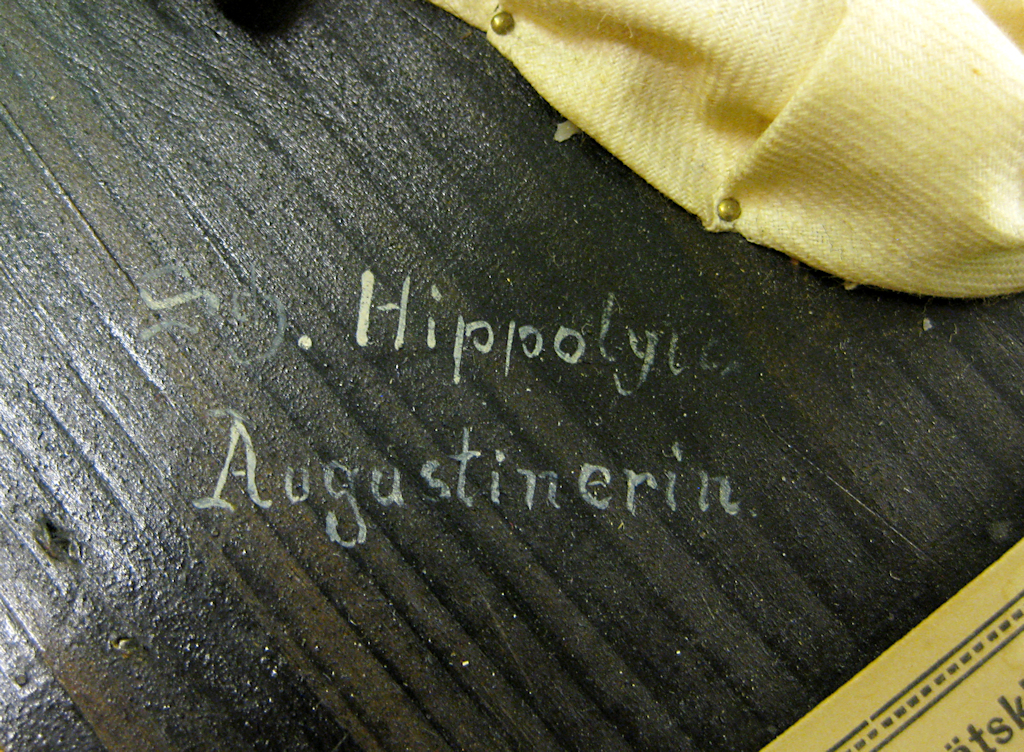

Stadin AO, the Helsinki Vocational College and Adult Institute, donated nine wax models, or moulages, to the Helsinki University Museum in 2013. Initially, no background information on the items was available, but the labels and signatures made it possible to deduce that the objects had been made by Sister Hippolyta and that they originated in Cologne, Germany. Using these snippets of information, it was possible to begin the detective work whose results I am presenting in this blog post.

In Sister Hippolyta’s footsteps

Johanna Maria Wery (1870–1962) travelled to Cologne in November 1890, aged 20. Cologne was located at a distance of less than 40 kilometres from Maria Wery’s home village of Großbüllesheim, but the short trip marked a turning point in her life. The young woman was a devout Catholic and intended to join the Augustinian nuns to devote her life to Christianity and helping others. She was welcomed with open arms. In the convent, Maria Wery was given the name Hippolyta, and after living as a novice for close to 10 years, she took her vows.

Fairly little is known about Sister Hippolyta. We know that she was good with her hands and especially skilled at handling wax. She created what came to be a source of great pride for the University of Cologne dermatology department, a collection of close to 1,000 moulages. Sister Hippolyta lived most of her life in Cologne, but moved in her later years to the Marienborn convent in Zülpich-Hoven, where she is also buried. However, the time Sister Hippolyta spent in Cologne is of most interest to our current story.

A few words on moulages

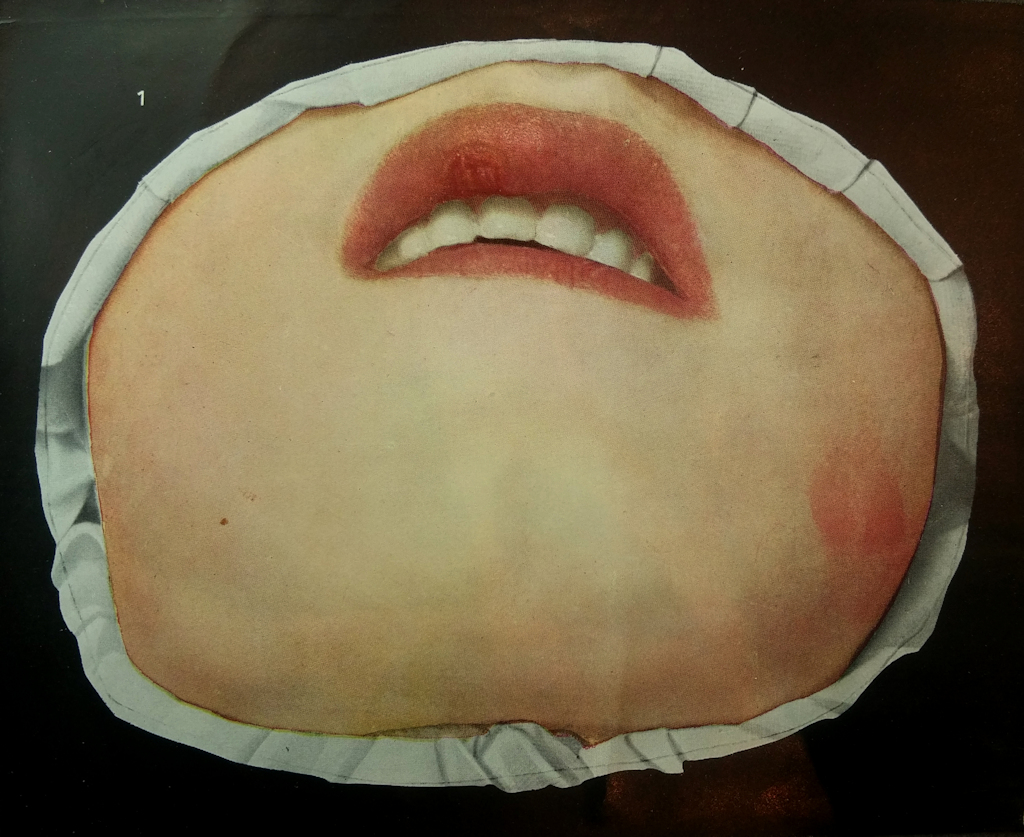

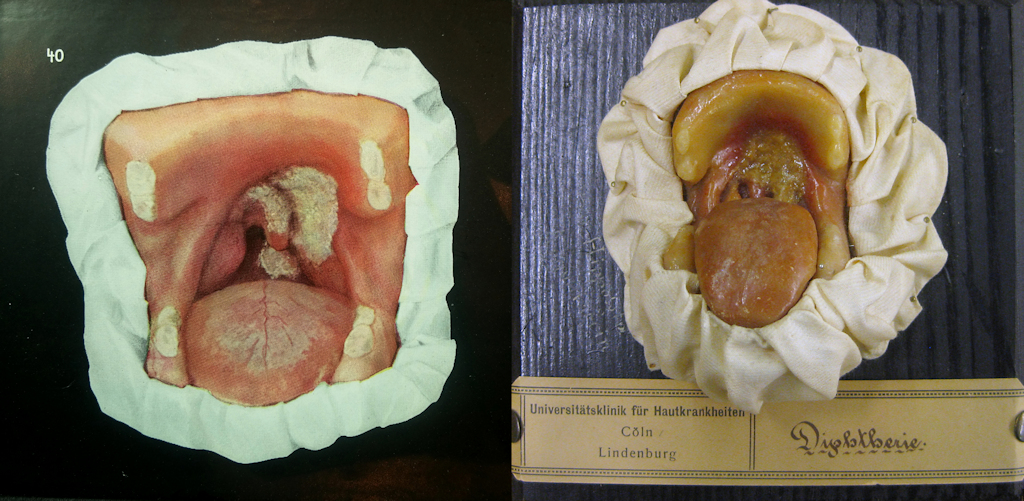

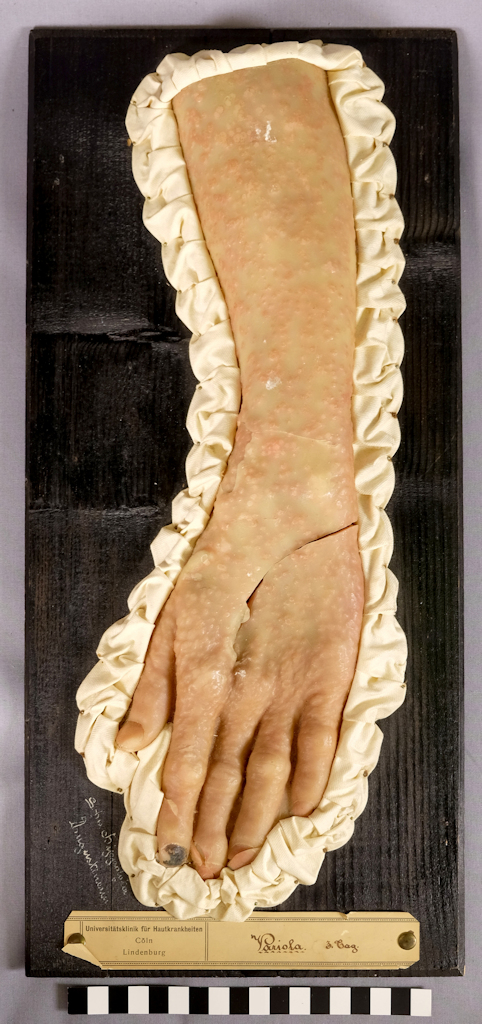

Moulages are three-dimensional wax models depicting skin diseases. They are created with plaster casts and made to look as realistic as possible with tinted wax, detailed painting, glass eyes and real hair. They should not be confused with the anatomical wax models created with a different technique, produced in Europe as of the late 17th century.

Moulaging was developed in the early 19th century, but its golden age was in the late 19th century. Between 1890 and 1950, moulages were produced and used widely in Europe, the United States, Russia and Japan. They were used in many specialist fields of medicine, but most commonly in the fields of skin and venereal diseases. Initially, they were used as clinical collections and to teach medical students, but their use expanded in the early 20th century: photos of moulages were published in medical books, and moulages began to be showcased in public exhibitions and used in health education.

The golden era of moulages lasted only a few decades. Black-and-white photography was not yet able to compete with the colourful and illustrative wax models, but as colour photography became more common, the use of moulages gradually declined. Previously, moulages had been the pride of many hospitals, which had even competed with the size and splendour of their collections, but as their value collapsed, unsuitable storage conditions proved disastrous for many sensitive wax objects. Some moulage collections were also destroyed.

A wax artist in the service of medicine

Maria Wery was familiar with wax as a material even before she moved to the convent, and she is known to have created religious wax figures in her home village. After the First World War, Sister Hippolyta began to make epitheses, or facial prostheses, for soldiers who had lost their nose, ear or cheek in the war.

It is not known when she began to produce moulages and where she learned the necessary skills. It is possible she was self-taught, or perhaps she was tutored by someone. In her convent, however, she was apparently the only nun able to produce moulages.

The nuns of Sister Hippolyta’s order had cared for the diseased of Cologne from as early as 1838, and it is likely that the nuns were responsible for the treatment of patients at the Lindenburg hospital in Cologne in the early 20th century. They certainly assumed this task no later than 1919 when the hospital was turned into a university hospital. Sister Hippolyta worked at the hospital for decades, cooperating productively with Professor of Dermatology Ferdinand Zinsser (1865–1952).

A dermatology department had been established at the Lindenburg hospital in the early 1900s, and dermatologist Ferdinand Zinsser had been hired as its head. Later, Zinsser became a docent, a professor, the dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Cologne and, eventually, the rector of the University. He headed the dermatology department and served as professor of dermatology until his retirement. It is likely that Professor Zinsser introduced the idea of creating moulages to Sister Hippolyta because he needed them for teaching purposes.

Venereal diseases were among Professor Zinsser’s interests, and his principal work, on syphilis, was published in 1912. The book is richly illustrated with 51 pictures of moulages. The moulages in the book look quite different from the ones produced by Hippolyta although some of the diseases and symptoms they depict are exactly the same. Is it possible that the moulages in the book are by another artist? Another possibility is that the techniques of photo manipulation available in the early 20th century were utilised when illustrating the book.

Nine moulages

The Helsinki University Museum collections include nine moulages produced by Hippolyta: four of syphilis, two of smallpox, and one each of chickenpox, diphtheria and follicular angina. The objects can be seen on the Finna.fi website [Link]. It is difficult to date the moulages, but the text on the labels offers some clues: ‘Universitätsklinik für Hautkrankheiten Cöln Lindenburg’. Because the university department did not exist before 1919, the moulages have either been produced after that year or the labels have been replaced with new ones when the dermatology department was annexed to the university.

The moulages of two smallpox patients’ arms can help date the objects because smallpox was almost entirely eradicated from Germany after 1922. It seems likely that Professor Zinsser commissioned the smallpox moulages from Sister Hippolyta at a time when there were still many smallpox patients. In fact, a smallpox epidemic raged in Germany from 1916 to 1922. The worst years were 1917 (3,000 cases) and 1919 (more than 5,000 cases).

How, when and why did the nine moulages end up in Finland and at the Helsinki Vocational College and Adult Institute? For a long time it seemed that this question would never be answered. However, Tarja Tomminen, the college’s student affairs secretary, decided to talk to some previous employees and found out that a Dr Lagus had donated the moulages in the 1960s to the college’s predecessor, the Helsinki school of nursing. Dr Lagus was retired at the time, but occasionally gave lectures to the student nurses.

The Dr Lagus in question was presumably Reino Lagus (1889–1974), a psychiatrist who made study trips to Germany at least in 1912, 1921, 1924, 1925, 1950, 1951 and 1952. Perhaps he visited Cologne on one of these trips to explore the department of dermatology and returned to Finland with the moulages.

A bleak fate

Today, the Cologne dermatology department’s collection of 1,000 moulages apparently survives only in the nine objects that, by a twist fate, ended up in Finland. Sister Hippolyta’s moulages suffered the fate of many other old teaching aids. They became outdated.

Having become unnecessary, the moulage collection was stored in poor conditions in a hospital cellar some time after the Second World War. The wax models remained in storage and their condition deteriorated until 1964 when the new director of the dermatology department, Gerd Klaus Stegleder, saw no other option but to dispose of the collection.

Henna Sinisalo, curator

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

Sources

Archiv der Cellitinnen Köln, Severinstraße. [Documents and press cuttings concerning Sister Hippolyta in the archives of the Augustinian nuns of Cologne.]

Fenner, F., Henderson, D. A., Arita, I., Ježek, Z., Ladnyi, I. D. (1988). World Health Organization.

Frank, M. (2006). “Plack an der Schnüss” – Die Abteilung für Haut- und Geschlechtskrankheiten. In M. Frank & F. Moll (eds.) Kölner Krankenhaus-Geschichten. Am Anfang war Napoleon (p. 409–422). Kölnisches Stadtmuseum.

Gutachten des Bundesgesundheitsamtes über die Durchführung des Impfgesetzes. Unter Berücksichtigung der Bisherigen Erfahrungen und neuer Wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnisse. Abhandlungen aus dem Bundesgesundheitssamt, Heft 2. (1959). Springer-Verlag.

Haavisto, E. (2012). Ylpön lapset. Vuosina 1918–1920 valmistettujen vahakuvien esinehistoria ja konservointi [thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences]. Theseus. Link.

Hoffmann, K. J. (2009). Schwester Hippolyta Wery und Schwester Honorata Feuser. Aus dem Leben zweier Ordensfrauen aus Großbüllesheim. Jahrbuch Kreis Euskirchen 2009, 81–82.

Karenberg, A. (2016). Email discussion.

Küpper, T. (ed.). (2006). Ferdinand Zinsser. Rektor 1928–1929. Rektorenportraits. Universität zu Köln. Accessed on 23 April 2021. Link.

Schnalke, T. (1995). Diseases in Wax. The History of the Medical Moulages. Quintessence Publishing Co.

Schnalke, T. (2004). Casting skin. Meaning for doctors, artists and patients. In S. de Chadarevian & N. Hopwood (eds.) Models. The Third Dimension of Science (s. 207–239). Stanford University Press.

Steigleder, G. K. (1977). Zur Geschichte der Universitäts-Hautklinik Köln. Der Hautartz 1977(28) (suppl. II), XV–XIX.

Tomminen, T. (2017). Email discussion

Wolters, M. (1988). Einfach da sein. 150 Jahre Genossenschaft der Cellitinnen nach der Regel des heiligen Augustinus Köln/Severinstraße. Parzellers Buchverlag & Werbemittel GmbH & Co.

Worm, A.-M., Sinisalo, H., Eilertsen, G., Ahren, E., Meyer, I. (2018). Dermatological Moulage Collections in the Nordic Countries. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 32(4), 570–580.

Zinsser, F. (1912). Syphilis und syphilisähnliche Erkrankungen des Mundes. Für Ärzte, Zahnärzte und Studierende. Urban & Schwarzenberg.