Resusci Anne is resting in the collection facility of the Helsinki University Museum, protected by dust covers. Anne bears the likeness of a beautiful, youngish woman with golden blonde hair and a blue-and-white tracksuit. Her eyes are closed and her mouth is slightly open. The manikin, its carrying case and other equipment for practising resuscitation were donated to the University Museum by the museum committee of Pitkäniemi Hospital in 2012. Pitkäniemi, Finland’s fourth oldest psychiatric hospital, is still operational today.

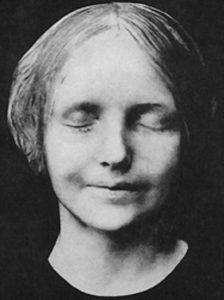

Used for practising cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), Resusci Anne is a remarkably realistic looking manikin, developed by the Norwegians Åsmund Lærdal and Björn Lind and the Austrian Peter Safar. The manikin was first presented in 1961 at the First International Symposium on Resuscitation in Stavanger, Norway. The face of the manikin is based on L’Inconnue de la Seine, a plaster cast death mask of an unidentified woman reputedly drowned in the River Seine in the 19th century.

L’Inconnue de la Seine

According to a story, a beautiful young woman was found drowned in Paris in the River Seine in the 19th century. Although lifeless, she appeared to be smiling faintly and peacefully. To immortalise her beauty, a pathologist at the Paris morgue made a plaster cast death mask of her face. The idea was also that someone might identify her later. This was sometimes done in cases involving unknown dead people, and the plaster casts – or even the bodies themselves – were placed on view at the morgue.

Numerous copies of the woman’s face were soon made, and people excitedly purchased them to display them as ornaments in their homes. Later, however, there has been some debate about whether the plaster cast is, in fact, based on the drowned woman because it is not very likely that a drowned person would be found smiling. In any case, the woman came to be known as L’Inconnue de la Seine (‘The Unknown Woman of the Seine’). From today’s perspective, displaying the death mask of a drowned person on the wall of your home seems slightly macabre.

The eerie, otherworldly smile of a woman fallen into an eternal sleep surely appealed to people of the period. The mysteries of life and death were a source of interest to many in the late 19th and early 20th century. The field of psychology was developing, and many people were fascinated by spiritism, symbolism, esotericism and other movements that strove to explain the spiritual world.

L’Inconnue de la Seine in art

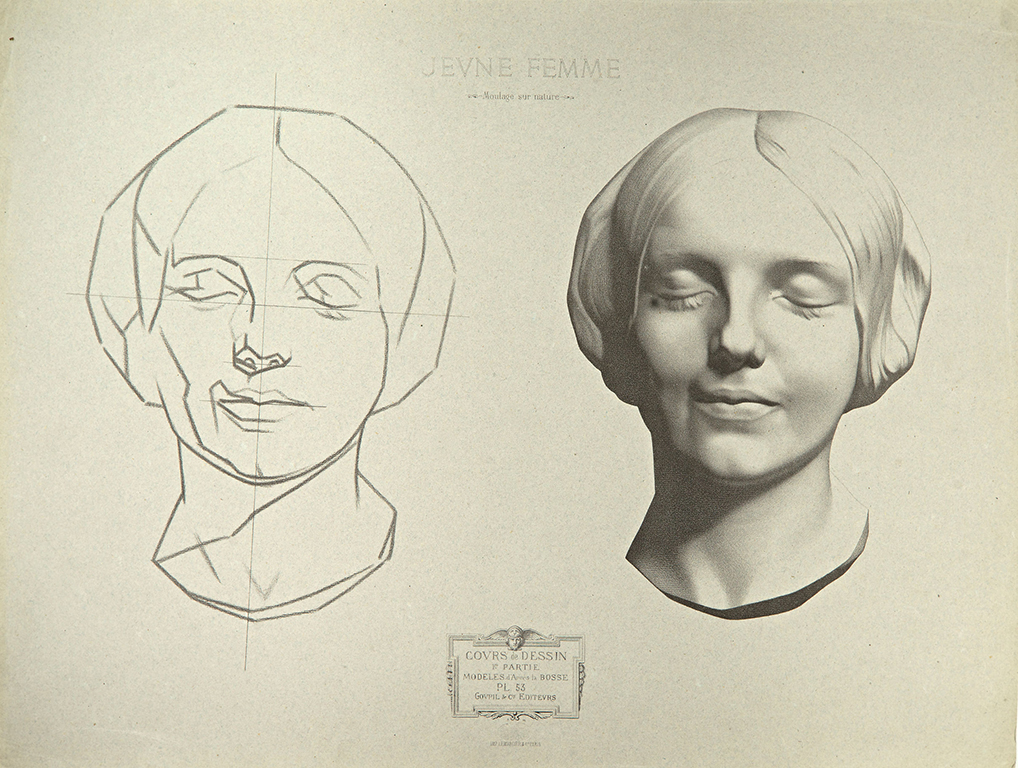

The face of L’Inconnue inspired a number of artists. The French author Albert Camus wrote about her, as did the Russian author Vladimir Nabokov in one of his poems. The American artist Man Ray created a study of the plaster cast. The woman’s face has etched itself in the minds of many visual artists, who have practised drawing the well-known plaster cast.

The collections of the Helsinki University Museum do not include a plaster cast of L’Inconnue de la Seine, but an image of her face can be found in the manual used at the University of Helsinki’s Art Room, which contains examples for practising the drawing of plaster sculptures. The Cours de Dessin drawing manual by Charles Bargue (1826/1827–1883) includes a drawing entitled ‘Jeune Femme’, which depicts L’Inconnue de la Seine.

The Cours de Dessin manual, which contained a number of model drawings, played an important role in teaching drawing in the 19th century. It has since been used by many artists and art schools across Europe. Charles Bargue and his fellow artist Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), who served as professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, originally published the manual in Paris in the 1860s. A copy of the manual was acquired for the University of Helsinki Art Room by the artist Adolf von Becker (1831–1909), who was the Art Room’s drawing master from 1869 to 1892. The Art Room is Finland’s oldest public art school and was, in fact, the country’s only public art school until the mid-1800s. The University has employed a drawing master from 1708 onwards.

The story of Anne

The case of L’Inconnue de la Seine, the woman whose identity was and remains unknown, is fascinating, but the story of Resusci Anne is also interesting.

Åsmund Lærdal was a Norwegian toy maker who succeeded in developing a new vinyl surface for dolls. Lærdal was inspired to develop a resuscitation manikin when his own son came close to drowning. He was rescued, but the incident shook his father to the core.

Around the same time, cardiopulmonary resuscitation had been developed to rescue drowning victims. Lærdal heard about the new technique and became intrigued. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation had been developed by the anaesthesiologist Peter Safar, and having been proved effective in 1958, this method was supplemented in 1960 with external cardiac massage by W. B. Kouwenhoven, J. R. Jude and C. G. Knickerbocker. The Norwegian Red Cross had also followed the developments with interest and decided to begin training people in the new resuscitation method. After all, anyone could suddenly find themselves in the position of helper. But how to practise mouth-to-mouth resuscitation? It would be unhygienic, not to mention inappropriate, between real people.

Lærdal, who had previous supplied the Swedish and Norwegian Red Cross with training supplies, teamed up with the anaesthesiologist Björn Lind to develop a life-like manikin with a vinyl face, hands and feet as well as an inflatable body to be used for resuscitation practice. Peter Safar gave some tips for a few final tweaks, suggesting, for example, that a metal ring be added inside the manikin’s chest for practising cardiac compression. The manikins became hugely popular and were sold around the world under the name of Resusci Anne.

Almost identical manikins still continue to be made, but the body is now made of foam rubber and the hair of plastic.

But where to find a face?

Åsmund Lærdal saw a plaster relief of L’Inconnue, possibly a souvenir, in his in-laws’ house in Stavanger. The beautiful, approachable face of a drowned woman – what could be a better choice for a CPR manikin!

The woman known as L’Inconnue de la Seine could not be rescued, but thanks to training with Resusci Anne, numerous other people have avoided the same fate.

Anna Luhtala, Curator

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

Sources and literature:

Ars Universitaria 1640–1990 – Teoksia Helsingin yliopiston Piirustussalista. 1990. Ed. Kati Heinämies

Forsius, Arno: “Tekohengityksen historia”, 2001 (updated 2003), on the website Lääketiedettä – kulttuuria – ihmisiä – kuvauksia historiasta (http://www.saunalahti.fi/arnoldus/resuscit.html, accessed 5 October 2020)

Nousiainen, Anu: “Anne-nukkea on käytetty hengenpelastuksen opettamisessa jo yli 50 vuotta – mutta onko Annella Seine-jokeen hukkuneen nuoren naisen kasvot?”, Helsingin Sanomat, 1 April 2017

Tjomslanda, Nina; Laerdalb, Tore & Baskett, Peter: “Resuscitation Great Bjørn Lind – the ground-breaking nurturer”, Resuscitation 65 (2005) 133–138 (https://foundation915.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/about-bjorn-lind.pdf, accessed 1 October 2020)

Zeidler, Anja: “Influence and authenticity of l’Inconnue de la Seine” in Steven Moore: A Reader’s Guide to William Gaddis’s ‘The Recognitions’ (1982) (http://williamgaddis.org/recognitions/inconnue/index.shtml, accessed 23 September 2020)