In May, the University of Helsinki is again organising several conferment ceremonies. To mark the occasion, our object of the month is the conferment outfit of the official garland-weaver of 1914.

Election of the garland-weaver

The tradition of electing a garland-weaver for conferment ceremonies dates back to the 1830s when the daughter of a professor was appointed to weave laurel garlands for all master graduands. When the number of graduands increased, a single person was no longer able to weave all garlands. As a result, in the late 1800s master graduands began to invite a companion to serve as their garland-weaver. An official garland-weaver was elected for the first time in 1890 to guide and supervise the weaving process. The roles were highly gendered, as women were not free to study at the University until 1901.

After the conferment ceremony of 1894, it became customary for the official garland-weaver to be elected on Flora Day on 13 May. Accordingly, on that date in 1914, a Wednesday, graduands met at 11.00 at the Old Student House and elected Margareta von Bonsdorff as the official garland-weaver. They then walked in procession to the von Bonsdorff family home at Bulevardi 11, where a smaller delegation of graduands gave speeches in Margareta’s honour and formally asked her to serve in the role. Her affirmative answer was announced from a window to a waiting audience including singers who responded by cheering nine times.

A baroness with an interest in chemistry and medicine

Baroness Margareta von Bonsdorff (1890–1955) came from an academically successful family of high noble rank. Her father was Professor of Surgery Hjalmar von Bonsdorff, and her father’s grandfather was Professor of Anatomy and Physiology Gabriel von Bonsdorff (1762–1831), who had been Finland’s first arkkiatri (archiatre, the highest honorary title awarded to a doctor in Finland). Margareta, or Greta, von Bonsdorff herself began studying at the University of Helsinki in 1908, where she pursued medicine and chemistry, fields considered suitable for women at the time.

Previous elections of the official garland-weaver had occasionally been contested and affected by political factors, but the 1914 election is said to have been unanimous. This may perhaps be attributed to the fact that Greta’s future husband Kai Donner (1888–1935) was the highest ranking master graduand at the ceremony in question. Kai had undertaken his first expedition to Siberia between 1911 and 1913 and was preparing in early 1914 for his second expedition by learning medical skills at the Helsinki Surgical Hospital at a clinic headed by Hjalmar von Bonsdorff. This was how he met Professor von Bonsdorff’s daughter Greta, whom he married later that year on 19 December 1914.

The conferment outfit of the official garland-weaver

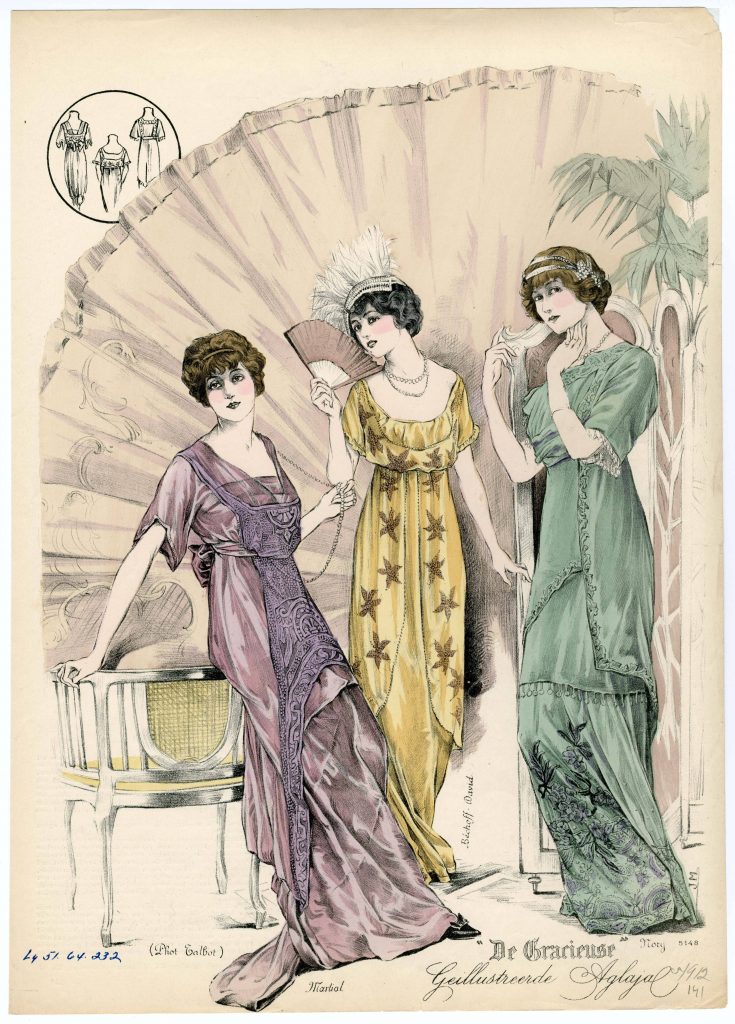

Greta von Bonsdorff’s outfit as official garland-weaver was made by the dressmakers Bergqvist & Wiman, who had a shop in Helsinki at Aleksanterinkatu 11. Sewn from off-white silk satin, the outfit reflected the fashions of the mid-1910s. The strictly corseted style of the early 1910s had been abandoned in favour of a softer, column-like silhouette showing signs of the more liberated designs of the 1920s.

The garland-weaver’s outfit has a narrow hem and a peplum or flounce at the hip, and the top part and chest are emphasised with folds, tucks and embroidery. The flounce is embroidered with a laurel garland, and the collar and sleeves are decorated with foliage. These details are beautifully captured in the studio portrait of Greta von Bonsdorff wearing the outfit.

The outfit appears to be quite simple, but a variety of hidden fasteners, hooks and press buttons keep each fold in its place and make it possible to put on and take off the outfit because no zipper suitable for festivewear had yet been invented. The top part of the outfit has a corset-like, bone-supported cotton lining, in addition to which the waist has an invisible belt. These ensure that the loose-fitting top part does not slide off or look sloppy under any circumstances, but stays in place as designed.

It is thought that Greta von Bonsdorff wore this outfit during the actual conferment ceremony. No photos of the event are known to exist, but an article in the Hufvudstadsbladet daily features a photo of the garland-weaving ceremony organised the day before at Restaurant Kaivohuone. The article reports that Greta von Bonsdorff wore a tasteful light-coloured outfit with two red roses attached to the front.

The Jäger conferment ceremony

The conferment ceremony of 1914 was the last one held at the Imperial Alexander University, and its atmosphere and arrangements received praise. Subsequently it came to be known as the Ostrobothnian conferment ceremony because so many of the organisers and participants were members of the Ostrobothnian student nations. One of them was Kai Donner, a member of the Pohjois-Pohjalainen Osakunta nation. The ceremony in question has also been called the ‘Jäger conferment’ because many of the participants – including Greta Donner’s new husband Kai – subsequently joined the Jäger Movement of Finnish volunteers who received military training in Germany.

In fact, the ceremony acted as a catalyst for the movement. The speeches given there were highly patriotic. In his speech as the highest-ranking master graduand, Kai Donner called for action against the Russians in so direct a fashion that Deputy Chancellor Edvard Hjelt forbade the publication of the speech.

The wife of an activist is widowed

After their wedding, Kai and Greta Donner lived in early 1915 on the Donner family estate at Ahdenkallio Manor in Hyvinkää. According to a letter Kai wrote to a friend, they lived a peaceful life, skiing and studying. Greta continued to study chemistry on her own although she had not registered at the University in the autumn. At the time, women of Greta’s social class typically abandoned their studies after marriage.

Soon both her studies and her peaceful life came to an end. As a result of his activism for Finnish independence, Kai was forced in 1916 to flee the gendarmes by escaping from a window of Ahdenkallio Manor, and the young couple subsequently moved to Sweden for a few years. After Finland declared its independence in 1917, Kai fought in the Finnish Civil War of 1918 and served in high-ranking military positions until returning to research work. Greta gave birth to six children from 1919 to 1933. She suffered several losses: her first-born died at the age of eight in 1927, and her father Hjalmar von Bonsdorff in 1932. Kai suffered from poor health as a result of his expeditions and eventually passed away at the age of just 46 in 1935. Greta Donner was left to care for her five children, of whom the youngest, Jörn, was just two years old at the time, and look after an apartment in Helsinki, the estate in Ahdenkallio and a summer residence in Bromarv. Birgitta von Bonsdorff donated her mother’s outfit of official garland-weaver to the Helsinki University Museum in 1990. The outfit was on display as part of the museum’s permanent exhibition from 2003 to 2014.

This object will be included in the museum’s new core exhibition, to be opened in the University of Helsinki Main Building in autumn 2023.

Helena Hämäläinen, curator

Sources:

Flander, Outi 2021. Sata vuotta sitten – poikatyttömuotia 1920-luvulla. Kuukauden esine – Huhtikuu 2021. https://www.kansallismuseo.fi/fi/kuukauden-esineet/2021/sata-vuotta-sitten-poikatyttomuotia-1920-luvulla Katsottu 23.3.2023

Gothóni, René: Donner, Kai. Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu. Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1997– (viitattu 23.3.2023)

Julkaisun pysyvä tunniste URN:NBN:fi-fe20051410; artikkelin pysyvä tunniste http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:sks-kbg-005410

(ISSN 1799-4349, verkkojulkaisu)

Harmo, Ahto 2018. Ylioppilaista, Suomen itsenäisyydestä ja sisällissodasta. Teoksessa Lyyra 2018, Helsingin yliopiston ylioppilaskunnan historian ystävien vuosikirja nro 4 (2018). Helsingin yliopiston ylioppilaskunnan historian ystävät ry. https://hyyhy.fi/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/hyyhy_lyyra_2018_web_FINAL.pdf

Helsingin nimikirja ja suomalainen osotekalenteri, 01.01.1914, s. 169

https://digi.kansalliskirjasto.fi/aikakausi/binding/1161818?page=169

Kansalliskirjaston digitaaliset aineistot

Helsingin Sanomat, 14.05.1914, nro 129, s. 4

https://digi.kansalliskirjasto.fi/sanomalehti/binding/1172386?page=4

Kansalliskirjaston digitaaliset aineistot

Helsingin yliopiston arkisto, Matrikkeli. 1908, läsnä olevaksi kirjoittautuneet opiskelijat.

Helsingin yliopisto, Ylioppilasmatrkikkeli 1853-1899. https://ylioppilasmatrikkeli.helsinki.fi/1853-1899/henkilo.php?id=20029

Hufvudstadsbladet, 29.05.1914, nro 146, s. 5 https://digi.kansalliskirjasto.fi/sanomalehti/binding/1182689?page=5

Kansalliskirjaston digitaaliset aineistot

Klinge, Matti. (1987). Helsingin yliopisto 1640-1990. 2. osa, Keisarillinen Aleksanterin yliopisto 1808-1917. Otava.

Klinge, Matti. 1978. Ylioppilaskunnan historia 1872-1917.3. osa, K.P.T:stä jääkäreihin. Helsingin yliopiston ylioppilaskunta ja Gaudeamus.

Kyoto Costume Institute Digital archives. https://www.kci.or.jp/en/archives/digital_archives/1910s/KCI_151

Leikola, Anto: Bonsdorff, Gabriel von. Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu. Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1997– (viitattu 23.3.2023)

Julkaisun pysyvä tunniste URN:NBN:fi-fe20051410; artikkelin pysyvä tunniste http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:sks-kbg-003148

(ISSN 1799-4349, verkkojulkaisu)

Louheranta, Olavi. (2006). Siperiaa sanoiksi – uralilaisuutta teoiksi : Kai Donner poliittisena organisaattorina sekä tiedemiehenä antropologian näkökulmasta. University of Helsinki.

https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/23363/siperiaa.pdf?sequence=2

Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, digital collections. https://cdm16028.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll12/id/11138/rec/13

Uljas, Tellervo 2013. Jörn Donner: ”Sielun yksinäisyyttä ei voi parantaa”. Eeva 2/2013. Muokattu nettiversio on julkaistu 31.1.2020. https://www.eeva.fi/jutut/jorn-donner-sielun-yksinaisyytta-ei-voi-parantaa