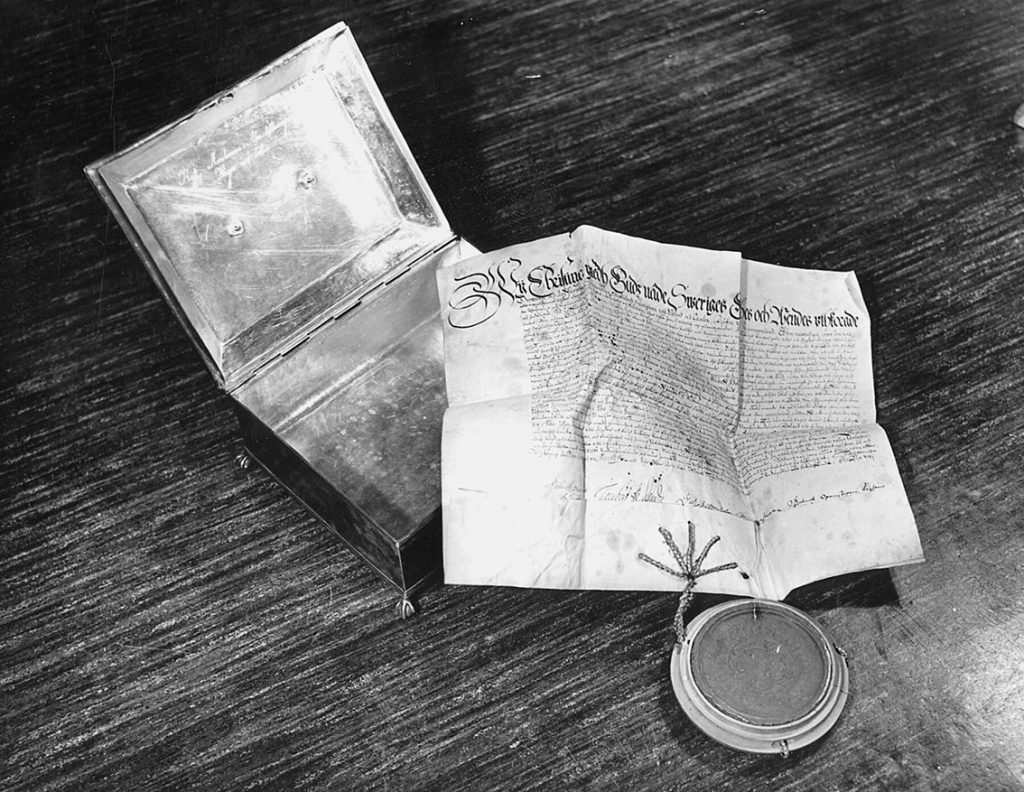

One of the unique objects in our museum collection is a document written in beautiful, elaborate handwriting, at the bottom of which are signatures and a large red wax seal attached with a string. The words Christina, Gud (‘God’) and Sverige (‘Sweden’) stand out on the first line. The document is the charter of the Royal Academy of Turku, written on parchment and dated 26 March 1640. This date is considered the anniversary and date of establishment of the current University of Helsinki.

In autumn 1827, soon after the Great Fire of Turku, Nicholas I of Russia decided to move the Academy to Helsinki, which had become the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland 15 years earlier. Also transferred from Turku to Helsinki were the charter, folded in a silver box, and other objects that had survived the fire.

Parchment, the paper of yesteryear

Parchment was used in Europe for centuries as a writing medium before paper became commonplace. Made of the skin of goats, calves or sheep, this writing material was invented in ancient Greece, although papyrus was more popular there. The material was developed and its quality improved in the city of Pergamon (now Bergama) in what is now western Turkey, particularly for use by scribes.

Parchment began to replace papyrus scrolls in the 4th century, when the first codices, handwritten manuscripts similar to the present books, were composed. Part of the reason for the popularity of parchment was that you could write on both its sides, unlike on papyrus. It was also recyclable: the text could be rubbed off and replaced with new writing. In the Middle Ages, parchment became a popular writing material in Europe. Although it gradually fell out of favour when a new material, rag paper, became more widespread during the 16th century, its use never ceased entirely.

Parchment remained the material of choice for many official and important documents, such as our University charter. Parchment has proved to be durable, with numerous parchment documents having been preserved in various collections.

What does the charter tell us and why was the Academy established?

The charter was signed by the members of Queen Christina’s Regency Council: Lord High Steward Gabriel Gustafsson Oxenstierna, Lord High Constable Jacob de la Gardie, Lord High Admiral Carl Gyllenhielm, Lord High Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, Lord High Treasurer Gabriel Oxenstierna and, as presenting official, Johan Silverstiärna.

When the Academy was established, Christina was just 13 years old. Her father Gustavus Adolphus (or Gustav II Adolf) had planned the founding of an academy in the eastern part of his empire, but died in the Thirty Years’ War in 1632. His important goal had been to instil the Protestant faith throughout the empire by training the clergy and officials at a new academy not weighed down by the baggage of Roman Catholicism. A seat of learning in the eastern part of the empire would also be more readily accessible to studious young men born there. In the 17th century, Turku was one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the eastern Baltic Sea region.

The charter notes that schools and academies have throughout the ages been considered nurseries and spawning grounds for the formation and development of the arts and sciences, good manners and virtues when they are properly taught and practised. It further states that the Academy, meaning the University, is to be set up and established in Turku as the site of instruction and practice in all permitted disciplines, such as the Holy Bible, law, medicine and other sciences.

The history of the document

For over three centuries, the charter was kept folded in a silver box. When the document and its box began to be investigated, it was deduced by the colour of the box and the traces on its surface that it had suffered from intense heat. It is thus possible that the charter survived the Great Fire of Turku thanks to the box. Or can the findings be attributed to the Second World War firebombs that caused considerable damage to the University Main Building?

Designed by C.L. Engel, the University Main Building was completed in 1832. On the third floor was a large venue for meetings of the University Senate, the University’s highest decision-making body, consisting of professors. Old photos indicate that the room contained treasures surviving the Turku Fire, such as marble busts of Queen Christina and Alexander I of Russia and large painted portraits of Russian emperors, who served as the University chancellors when Finland was a Grand Duchy. According to Rector K.R. Brotherus, plans were made in the early 1930s to use the old Senate chambers as a museum venue. Was the box containing the charter kept in the venue at the time? The photos do not tell us this.

In 1978 the University’s administration building was completed in the corner of Fabianinkatu and Hallituskatu (now Yliopistonkatu) opposite the Porthania building. Facilities with a higher ceiling than in the other rooms were built in the basement floor (K3) of the administration building for the University Museum exhibition. The charter was treated by a conservator in London in the early 1970s. It was decided that the document would be permanently removed from its silver box and framed. Just 10 years later the document was on display in the University Museum’s permanent exhibition.

The large portraits of emperors acquired in the 19th century found their places in the museum facilities, as did many other University treasures, old research equipment and observation instruments. The University Museum welcomed groups for booked visits and was open to the public on the first days of the academic year from the 1990s. After the University Museum moved to the Arppeanum building on Snellmaninkatu in 2003, the charter was on display in the permanent exhibition on the fourth floor for six days a week from 2003 to 2014.

The Arppeanum building and its exhibition were closed to the public in spring 2014. The following year, the charter took pride of place in the Power of Thought exhibition on the story of the University, mounted in the Main Building. At the time, the old frame and matting were removed and replaced with new, better-quality materials. The exhibition was closed in late 2020, but soon the public will again be able to view the document in a new location.

This object will be included in the museum’s new core exhibition, to be opened in the University of Helsinki Main Building in autumn 2023.

Pia Vuorikoski, Head of Exhibitions

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services

Sources cited and consulted

Pekka T. Heikura. Pergamentti oli keskiajan paperi. Kemia 1/2012.

”Rehtori K. R. Brotheruksen haastattelu”. Kansan kuvalehti 13 February 1931.

Mirkka Lappalainen. Pohjolan leijona. Kustaa II Aadolf ja Suomi 1611–1632. Helsinki, 2014.

Ivar A. Heikel. Helsingin yliopisto 1640–1940. Helsinki, 1940.