In the 19th century, the ideology of nationalism spread across Europe, taking hold in Finland too. During this time of national awakening, researchers and artists began to seek the material and immaterial roots of Finnish identity. The study of Finnish and Finno-Ugric languages was deemed important. Oral cultural traditions were preserved using an early recording device called a phonograph.

From a sheet of tinfoil to a wax cylinder

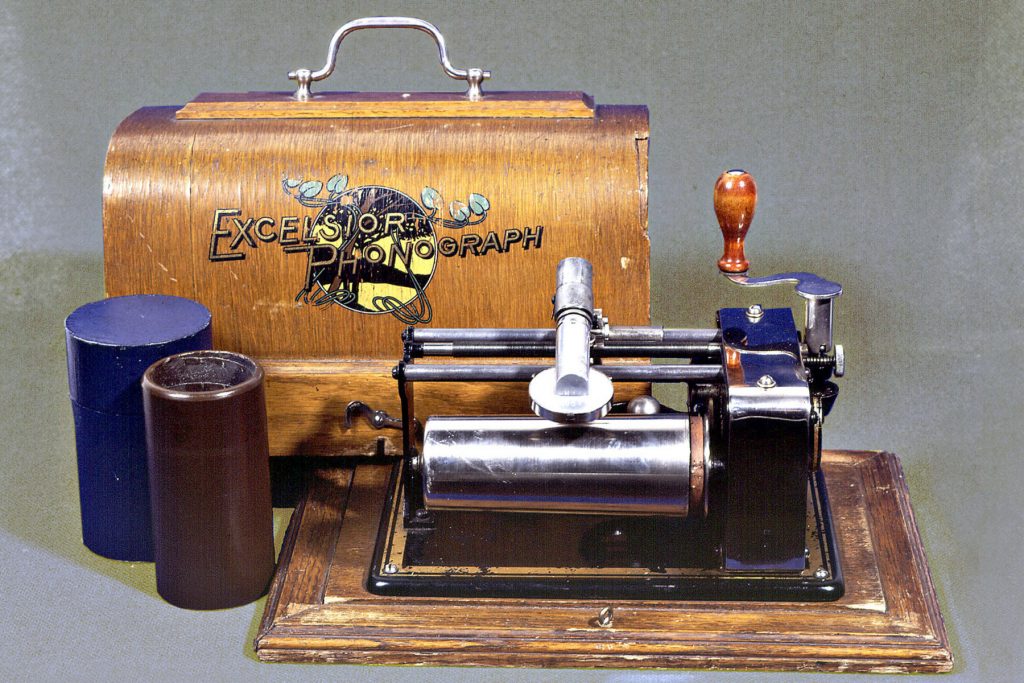

The phonograph was the first device for recording and playing back sound, using the medium of wax cylinders, or phonograms. Connected to the device was a horn into which the subject spoke. The phonograph in the collections of the Helsinki University Museum Flame was manufactured by Excelsior at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The earliest known device for recording sound, the phonautograph, was invented as early as 1857 by the Frenchman Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. However, the device was not designed to play back sounds. In November 1877, Thomas Alva Edison announced he had invented the phonograph, originally called the ‘talking machine’. Edison designed his phonograph for recording telephone messages, but it was soon discovered that the device could also record and replay music.

The original phonograph had a tinfoil-wrapped cylinder rotated with a crank. Speaking into the horn would make a stylus or needle vibrate, and the vibrations would be etched onto a thin sheet of tinfoil. The recorded sound could be played back with the horn, without amplifying the signal electrically. Later, the cylinder covered with tinfoil was replaced with a wax cylinder, which was better suited for repeated use.

The first phonograph was manufactured by the machinist John Kruesi in August 1877. Edison trialled the device by reciting the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”. To his own surprise, the phonograph played back the words perfectly. Phonographs were sold commercially from 1890 to 1925. Initially, it was impossible to mass-produce duplicate wax cylinders, which meant performers had to repeat their performances to amass a quantity of cylinders. As the recording process was acoustic and microphones were not yet known, performers had to speak or sing directly into the horn.

Gramophone disc records were patented in 1887. The gramophone operated on the same logic as the phonograph, but could not record. Although the sound quality of the phonograph is better, its sound output is quieter. Gramophone records were used until the 1960s when they were replaced by vinyl records made of more durable PVC plastic.

Gradually, phonograph cylinders established their user base among popular performers, whereas gramophone records were the preferred medium of opera singers and leading orchestras. In the 1920s the wax cylinder was overtaken on the pre-recorded music market, but its use continued until the 1950s for devices such as dictation machines.

Recording languages related to Finnish

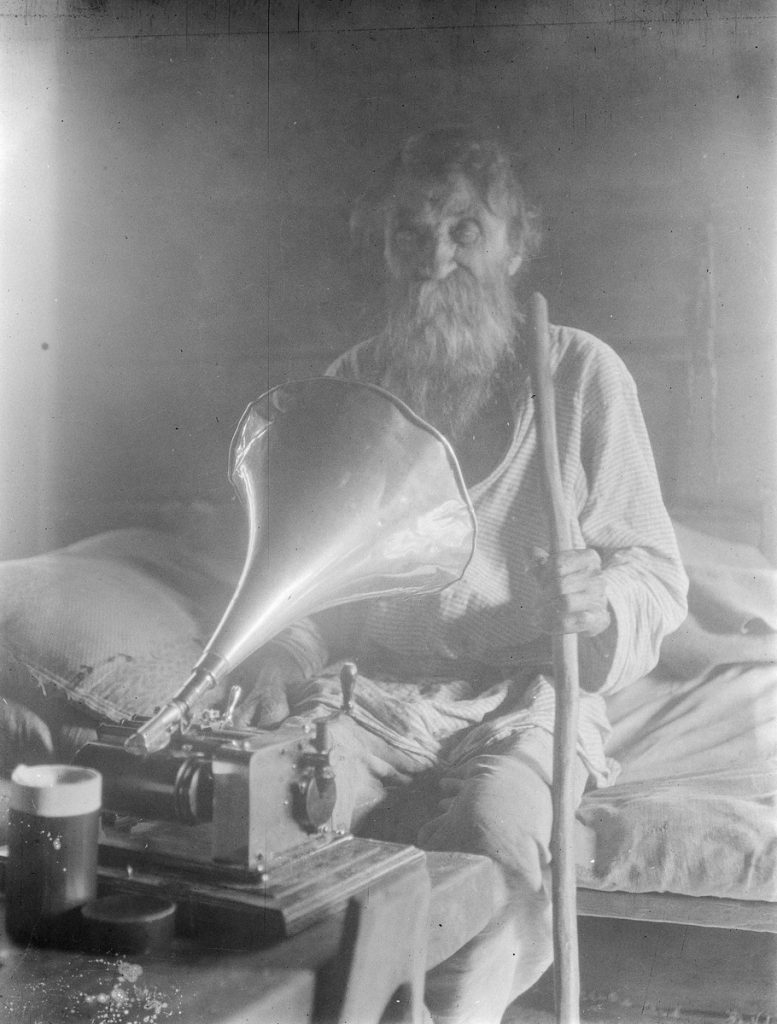

Finnish researchers came to know the phonograph as early as the late 19th century. Recordings had played an important role in fieldwork on Finno-Ugric language studies, as the lack of early written material had meant that research relied on the collection of data from the speakers of these languages.

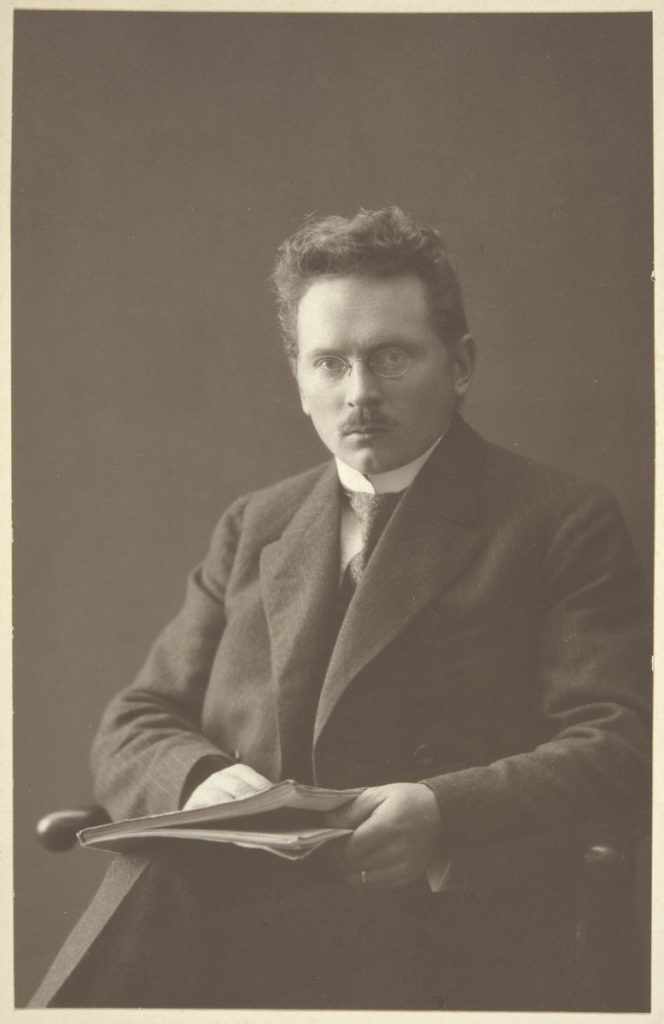

The phonograph in the museum collections was used by Professor Lauri Kettunen. He was a significant collector, researcher and publisher of Finnic linguistic and cultural material, and devised a map of Finnish dialects and dialect areas, together with samples and explanations.

Kettunen was born in 1885 to an educated farmer from Joroinen and a shopkeeper’s daughter from Kuopio. After graduating from a coeducational school in Kuopio, Kettunen began to study the Finnish language and Finnish literature at the Imperial Alexander University in Helsinki. He progressed quickly, completing his doctoral degree at the age of 27, and was appointed professor at the University of Helsinki in 1929.

During his university studies, Kettunen travelled to the Värmland region of Sweden to record the language and traditions of the ‘Forest Finns’, that is, Finnish migrants from the Savo and Häme regions. Their language was a fossilised version of the dialects spoken by the Savo inhabitants when they migrated to Sweden at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 1920s, Kettunen served as a professor at the University of Tartu in Estonia. He made research and recording trips particularly in areas inhabited by Estonians, Votians, Vepsians and Livonians. He is known as a defender of Estonian freedom and culture. As noted by Ritva Haavikko: “This sturdy, nimble and cheerful ‘scholarly traveller’ was equally at home in cottages and manors, and made friends with his expert language informants.” A great number of Kettunen’s phonograms, or wax cylinder recordings, are now in the collections of the Finnish Literature Society.

Folk music on wax

Another phonograph enthusiast was Armas Otto Väisänen, a folk music scholar. He was born in 1890 in the village of Savonranta into a poor family. Thanks to a wealthy patron, he was able to commence his studies in music and folk poetry at the Imperial Alexander University. He completed a doctoral degree, was appointed docent of musicology and eventually became the first professor of musicology in 1956.

Väisänen had had an early interest in archiving the Finnish national heritage and, while studying in Helsinki, associated himself with the Finnish Literature Society. He undertook research trips to Estonia, Ingria, White Karelia and areas populated by the Mordvins, and recorded pastoral music, melodies played on the kantele and jouhikko string instruments, laments, White Karelian joiks, and the rune singing of the Setos living in Setomaa in south-eastern Estonia. Väisänen’s phonograms, or wax cylinder recordings, can now be found in the collections of the Finnish Literature Society.

A.O. Väisänen achieved national fame as the presenter and producer of the Yle public service broadcaster’s folk music programmes in the 1930s when he strove actively to revive public interest in the genre. The folk music recordings associated with his programmes are now among the most valuable historical sources of folk music in the Yle collections.

Väisänen also carved out a long career as the director of the Helsinki folk conservatory, in addition to which he was the chair or member of several associations, societies and foundations. Moreover, he actively advocated for the construction of a museum for the Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela in Tarvaspää, Espoo.

This object is on display in our museum’s new core exhibition, now open in the University of Helsinki Main Building.

Jaana Tegelberg, Head of Collections

Translation: University of Helsinki Language Services.

Sources

Asplund Anneli: A.O. Väisänen. https://kansallisbiografia.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/8195 [accessed 3 October 2023]

Estofilia 100. https://estofilia.finland.ee [accessed 13 October 2023]

Fonografi. https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fonografi [accessed 3 October 2023]

Gramofonilevy. https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gramofonilevy [accessed 3 October 2023]

Gronow Pekka, Saunio Ilpo: Äänilevyn historia, WSOY 1990

Haavikko Ritva: Lauri Kettunen. https://kansallisbiografia.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/6999 [accessed 10 October 2023]

Herttua Aleksi: Ensimmäinen fonografi keksittiin vuonna 1877, ja se toisti ensi töikseen sanat tunnettuun lastenlauluun. Article, Tekniikan maailma 15A.2020.

Finnish Literature Society. Fonogrammit. https://fonogrammi.finlit.fi/ [accessed 10 October 2023]

Thomas Alva Edison. Smithsonian Institution website. https://www.si.edu/object/thomas-alva-edison%3Anpg_NPG.65.23 [accessed 11 October 2023]