The first follow-up of the Transit-project is now successfully completed! Here’s some preliminary findings:

The first questionnaire was executed in turn of the year 2014–2015, during the last year of comprehensive school (9th grade). At that point the joint application for secondary education was ahead, but the final choices had not been made yet. The first sample consists of 445 students altogether; 284 (64%) of them were Finnish-origin majority, i.e. by definition both parents and their offspring were born in Finland. Whereas, 161 (36 %) of them were youth with immigrant origin, i.e. in broad terms, persons who are born abroad, or whose parents are born outside Finland.

The follow-up data was gathered from the youth during October 2015, when the joint application for upper secondary education was assuredly finilised and the youth settled for the upper secondary education. For the follow-up, we were able to get the information concerning the upper secondary transitions from 412 of those youths that participated in the first survey (93 %). The sample loss for the first follow-up was 34 (n = 17 immigrant-origin youths). 61 per cent of the youths answered to a questionnaire concerning their educational status in upper secondary education, where 30 per cent of the youths were not reached but the information was gathered from the joint application system and upper secondary schools.

We were especially interested if immigrant-origin and Finnish-origin youth share the same expectations towards upper secondary education, and is the transition to upper secondary education different among immigrant-origin youth when compared to Finnish-origin youth?

High hopes: Expectations for upper secondary education

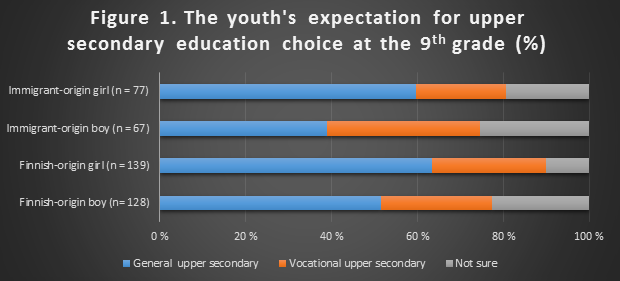

The youth’s school choice after 9th grade was inquired in the first survey through an open question about their expectted first choice for secondary education. The answers were categorized as general upper secondary school, vocational school or unsure, the latter including both the respondents with an explicit mention of being unsure as well those who left the question unanswered.

In general, the youth’s expectations for upper secondary education were rather similar. Of all the youth, a little more than the half were aimig for general upper secondary education while roughly a fourth were going to apply to vocational schools. Although the Finnish-origin youth were aimig for general upper secondary school slightly more often than the immigrant-origin youth, the difference was not significant enough to imply that the mere origin, either Finnish or immigrant, would predict the youth’s choice between upper secondary and vocational education. Nevertheless, in comparison with origin and gender, girls were aimig for upper secondary education more often than boys, the extremes being Finnish-origin girls and immigrant-origin boys. Girls seemed to be surer about their choice than boys. Of the boys with immigrant origin, more than a fourth either left the question unanswered or reported being unsure about their school choice.

In addition to the school choice, the youth also estimated their actions after 9th grade with statements about continuing to 10th grade, seeking a job and taking a gap year. The statements were not exclusive, so a respondent could simultaneously estimate a high probability for e.g. seeking a job and applying to a school.

By average, the youth with Finnish origin were aiming for general upper secondary schools with slightly stronger certainty than the immigrant-origin youth. Girls were aiming for upper secondary education with more certainty than boys, who were more certain about applying to vocational education. However, these differences were not statistically significant. Boys with immigrant background stood out from the data as they averaged higher on their estimation about applying to vocational school and seeking a job.

One of our background assumptions was that the difficulties the immigrant-origin youth have in attaching the upper secondary education, might have its explanation on socio-economic background factors and difficulties in learning. We used logistic regression analysis to analyse whether these factors as well as goal orientations might have an effect on expectations concerning upper secondary education choices.

Generally as for the goal orientations of learning, schooling difficulties and school appreciation, the logistic regression analysis revealed that especially avoidance orientation, learning orientation and schooling difficulties enhances the educational choices. Those youths that were more avoidance orientated, and those who have severe difficulties in schooling, seemed to avoid the (academic) general upper secondary education. Nevertheless, the youth that set their goal-orientation on learning (compared e.g. with achievement-orientation), choose also statistically often vocational education.

In the second models of the analysis, we added the socio-democraphic features (family’s education level, origin and gender) of the youth into the analysis. The outcomes validated earlier findings stating that educational attachments and achievements socio-economically related. We run the analysis for several dimension measuring immigrant-origin related features that might have an effect on the upper secondary education choices, e.g. the country of the origin, the generation of the immigration, the Finnish skills of parents and the youths, but none of them proved statistically significant effect on choices for the upper secondary education. The only factor that had a strong effect was the education level of parents: university educated parents increased the odds for choosing the general upper secondary education and decreased the odds for the vocational choice. As the origin was included simultaneously in the model 2, we might argue that there are no statistically significant differences in upper secondary education expectations between immigrant and Finnish origin youth, if the effects of the goal-orientations, attitudes and schooling difficulties are taken into account.

First steps taken: Transition to upper secondary education

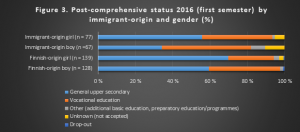

We were able to follow the transition from comprehensive lower secondary education to upper secondary tracks from 412 of our respondents. Figure 2 illustrates the intertwinement of educational expectations at the 9th grade and the post-comprehensive status at the first semester after comprehensive education. Generally, the youth had achieved the upper secondary track they expected to apply at the 9th grade quite well. As for general upper secondary education, over 90 per cent of Finnish-origin youths were in the education track they had applied for. Among the immigrant-origin youth, there was more mismatching of the expectations and the destinations: 24 per cent of boys (n = 6) and 15 per cent of girls (n = 7) that were applying for general upper secondary did not apply or were not accepted to general upper secondary education. The mismatching was more obvious among immigrant-origin boys. They were also most often located in additional or preparatory programs. The ones, who were still hesitating their choices a couple of months before the joint application, were most often accepted to vocational education, especially immigrant-origin youth. Fifth of the immigrant-origin youth hesitating their choices (3 girls and 5 boys) were in additional or preparatory programs or was not accepted to upper secondary education. In general, the group of immigrant-origin youth seemed to share more variation in transition from expected choices to attaching upper secondary education. Based on plurality and variety of choices of immigrant-origin youth, it can be argued that upper secondary choice was somewhat easier for Finnish-origin young.

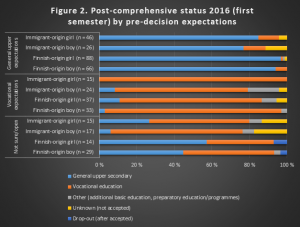

The variety of post-comprehensive status is apparent in Figure 3. Generally, it seems that Finnish universalistic transition regime is working reasonably well: less than five per cent of the youth were not accepted in education or dropped out from it; dropping out and not accepted being more common among immigrant-origin youths. Second generation immigrants seemed to follow the educational paths of the Finnish-origin youth, whereas first generation immigrants were navigating more often to vocational education and other additional education programmes.

The variety of post-comprehensive status is apparent in Figure 3. Generally, it seems that Finnish universalistic transition regime is working reasonably well: less than five per cent of the youth were not accepted in education or dropped out from it; dropping out and not accepted being more common among immigrant-origin youths. Second generation immigrants seemed to follow the educational paths of the Finnish-origin youth, whereas first generation immigrants were navigating more often to vocational education and other additional education programmes.

Observing the post-comprehensive status more detailed the pathways were gendered in both Finnish-origin and immigrant-origin groups. As girls preferred general upper secondary education in their expectations, they have also more often been selected for one. There seem to be more plural pathways for immigrant-origin boys, where the vocational track is more common than others and almost one fifth of the boys are in different additional or preparatory programs, or we have lost their track.