Holberg Prize Laureate 2015, Marina Warner invited five young Nordic scholars to a Masterclass on “Living in Words: The Question of Myth”. Warner – a novelist, historian and mythographer – has focused on stories and story-telling, “[b]oth from the perspective of illusion, which often has an ideological and political component, and all the way across to the conception of myth as a deeper and poetic truth … to explore long-lasting, but often disregarded forms of expression, such as popular stories and vernacular imagery in order to understand interactions of culture and ethics.”

Marina Warner (left), Houman Sadri from the University of Gothenburg, Marion Poilvez from the University of Iceland, Eemeli Hakoköngäs from the University of Helsinki, Anna-Liisa Tolonen from the University of Helsinki, and Per Esben Svelstad from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Photo: Julia Beate Bådsvik / The Holberg Prize Organizers.

I was one among the participants of the Masterclass, encouraged to share from the stories I work with and to explore the ways they make sense of the world around. This is the written version of my presentation at the occasion.

* * *

A mother was taken captive and her seven sons with her. They were all brought before the king. He commanded the eldest of the boys to renounce his religion but the boy, proving that the king had no authority over him, refused. He was put to death immediately. The same happened to all the brothers, one after another, until only the one last was left. At this point, the king turns to the mother.

“See what I have done! Come, tell your youngest one to obey me. Save his future and yours.”

So she obeys and steps forth. She talks to her son in their common native language. Then the boy, only a child, rushes to the king wanting to be killed like his brothers and as quickly as possible.

Now only the mother and the king are left, surrounded by the corpses of her dead sons. And I am puzzled; the story is not finished yet but I do not know how to go on.

* * *

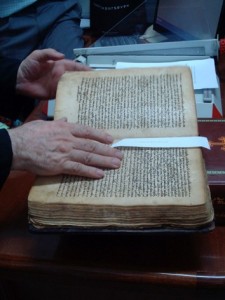

Everyone who opens their Bible should realize that they are not alone. Even when it is kept closed, the Bible talks in our cultures and societies with multiple voices, because in it, as in many other holy scriptures, different stories abound. It is often impossible to discern the oral traditions, which preceded – and perhaps determined – the known literary versions of the stories. But it is just as impossible to claim that their oral communication would have disappeared, as if the written word had replaced it. The Bible is recited, sung, illustrated, translated, excerpted, reorganized and so forth on a daily basis… Some of its parts may be put to sleep for a hundred years; yet, there are no letters so dead that they could not be brought back to life.

The oral communication of scriptures never ceased and much of what makes up the Bible continued its life also outside of it. Such is the case of the story you just heard, about the mother who lost her seven sons. I wrote it down last week, oneThursday morning at work. But I also took it from “the Bible”, from the Books of the Maccabees (2 Macc 7; 4 Macc 8:1–18:24), or from the Rabbis, from Christian hagiography, from the hymns of the Oriental Churches, the frescoes, or the medieval illustrations of the Psalter…

* * *

The story of the mother and her seven sons is traditionally known in two different historical contexts of conflict and resistance. In the Christian traditions – and from the Middle Ages onward, increasingly also in Jewish traditions – it is often told as part of the history of the Maccabean Revolt (160s bce). The seven sons are known as martyrs, fearless witnesses for faith, and their mother is credited above all for her steadfastness and selflessness/altruism. They help to save their nation from tyranny.

Taking the role of adult men who are absent from the scene, the mother and her young offspring exemplify the virtues of courage and manliness. They rise to represent the backbone and morale of their oppressed community. Their example stresses everyone’s involvement and commitment to the cause, for if these people could do it, what excuse could anyone else have not to bother…?

In the Rabbinic traditions, the story is told in the context of the Roman conquest of Jerusalem. The mother with her sons shows herself a heroic but desperate figure, illustrating in an emotional way the bitter fate of the destroyed city and its people.

But here, winners and losers are not determined according to casualties. Rather, the woman and her children counter masculine presentations of power. By their tragic passive aggression, incapability as well as unwillingness to conquer, they not only reveal the weakness of their persecutors but also question the value of religious submission and challenged well-known examples of heroic faith, such as that of Abraham.

In addition to conflict situations, where resistance needs to be motivated and defeat glorified, stories of martyrdom are also told during times of peace. The memories of martyrs are cherished to prompt maintenance of a distinct religious identity. They warn against cultural assimilation, which the story-tellers often associates with spiritual laziness. It is dangerous to feel at home in a foreign environment… Whatever the situation, one should make sure to educate one’s children like the mother of those seven boys.

The conclusion of the story, the part which I was hesitant about, exemplifies the multi-functionality of stories in an outstanding way. Why? Because we can’t decide what happens to the mother! The story-tellers in East and West, from early on, stress her role in the event. It is really only the mother’s destiny that signifies the point of the whole story. We are interested in knowing how she felt and managed the situation. But it is as if she had left us with a range of alternatives. At one extreme, her joy and pride color the scene. Lifting her hands up in praise amidst the bloody scenery, as if rewarded, she astonishes us. They say she has become as hard – no, harder – than men. At the other extreme, she collapses, falls in despair, her mind breaks apart and she kills herself. She has been made into a graveyard. And in between these two, there are various mixes of cries and laughter, of loss and satisfaction, for each story-teller to make use of.

* * *

Stories of martyrdom have potential for various uses, not least because of their power to narrate a conflict with a religious cause. They can give cosmic, universal, and moral dimensions to what was once a local catastrophe. History is skimmed through in order to (re)discover spiritual and practical examples of self-sacrifice at the frontier. Also suffering today requires reasons, justification, glorification, denial, victimization and humiliation.

* * *

In April 2012, I was in Jerusalem. With a friend of mine, we decided to attend a prayer for the Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons. It was an ecumenical event organized at a monastery. Christians, Muslims and Jews were invited. After the opening, a woman stepped forth. She held a photo of her four sons, who were all in jail, and she told us what had happened to them, one after another.

– Haraam, this woman has lost everything! I whispered to my friend. I was wondering if the poor widow was left with any relatives at all to provide for her. As we were there, in the to this day quite patriarchal society, my reaction came in as natural, or so I thought.

– But she is not alone, my friend responded, pointing to the man who was sitting in the first row. – That’s the father of the boys.

And I realized: she is the mother of my story! She gets to speak in public; she is the one to represent their broken home, the disfigured nation. She embodies the losses and hopes of these people, the right to resist and exist. I had a thousand questions: How do you do that? Whose mouth is that, whose tears, whose womb? Whose words do you use? What choices were you given? Are you not going insane? But I was not given answers; we were there to lament, to feel her pain perhaps, hoping to be comforted in her shadow.

And some two kilometers away, inside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, in the quiet of the Jewish quarter, there is a narrow shadowy alley with long steep stairs. Someone once told me that if ever I pass by, I should climb those stairs carefully, one by one. And there, I should recall a woman who once upon a time lost all her seven sons in just one day…

Text: Anna-Liisa Tolonen